[

] 103

Making stream flow monitoring

work for biodiversity and social justice

Nicky Allsopp, South African Environmental Observation Network

H

ow does a long-term programme monitoring flow rates

from afforested mountain catchments result in a ground-

breaking poverty relief programme? The Working for

Water programme of the South African Government uses scien-

tific evidence to justify the removal of invasive alien plants on

the basis of their detrimental economic impact, whilst providing

employment for unemployed people. This evidence derives from

a monitoring programme started several decades earlier with

quite different objectives.

In 1935, at the fourth Empire Forestry Conference, hosted in South

Africa, concerns of farmers’ associations that plantation forestry

was drying up rivers were debated. Swift action followed with the

establishment of a forestry research station that year at Jonkershoek,

near Cape Town. The first stream flow gauging weirs, based on the

paired catchment principle, began monitoring water runoff in 1937.

Following the Second World War a network of gauging weirs was set

up in mountain catchments around the country in different climatic

regions, with different vegetation. The Jonkershoek data represent

some of the oldest stream flow monitoring records in the world.

Monitoring stream flow is important in South Africa as surface runoff

accounts for 77 per cent of the country’s current water usage.

The resulting stream flow catchment monitoring data

confirmed that plantations of exotic trees used more

water than indigenous vegetation. These data were

used to regularize the forestry industry and, as a conse-

quence, practices adopted to ameliorate water use by

plantations enabled the forestry industry to recently

attain Sustainable Forestry Certification.

In South Africa, most of the invasive alien plant species

are woody plants, many of which have spread from

plantations. They have invaded all important terrestrial

biomes, cover about 10 per cent of the land surface and

most riparian systems, and threaten much of the unique

biodiversity of the country.

1

It is recognized that inva-

sive alien vegetation impacts ecological functioning and

ecosystem services, invades otherwise productive land

and intensifies the impacts of fire, floods and soil erosion.

Data from the experimental catchments were used to

show that almost 7 per cent of water resources were being

lost to invasive plants in the catchments and along rivers,

and in cities like Cape Town, 30 per cent of available water

was lost to these plants.

2

Furthermore, clearing invasive trees

could be done at a fraction of the cost of building newwater

G

overnance

and

P

olicy

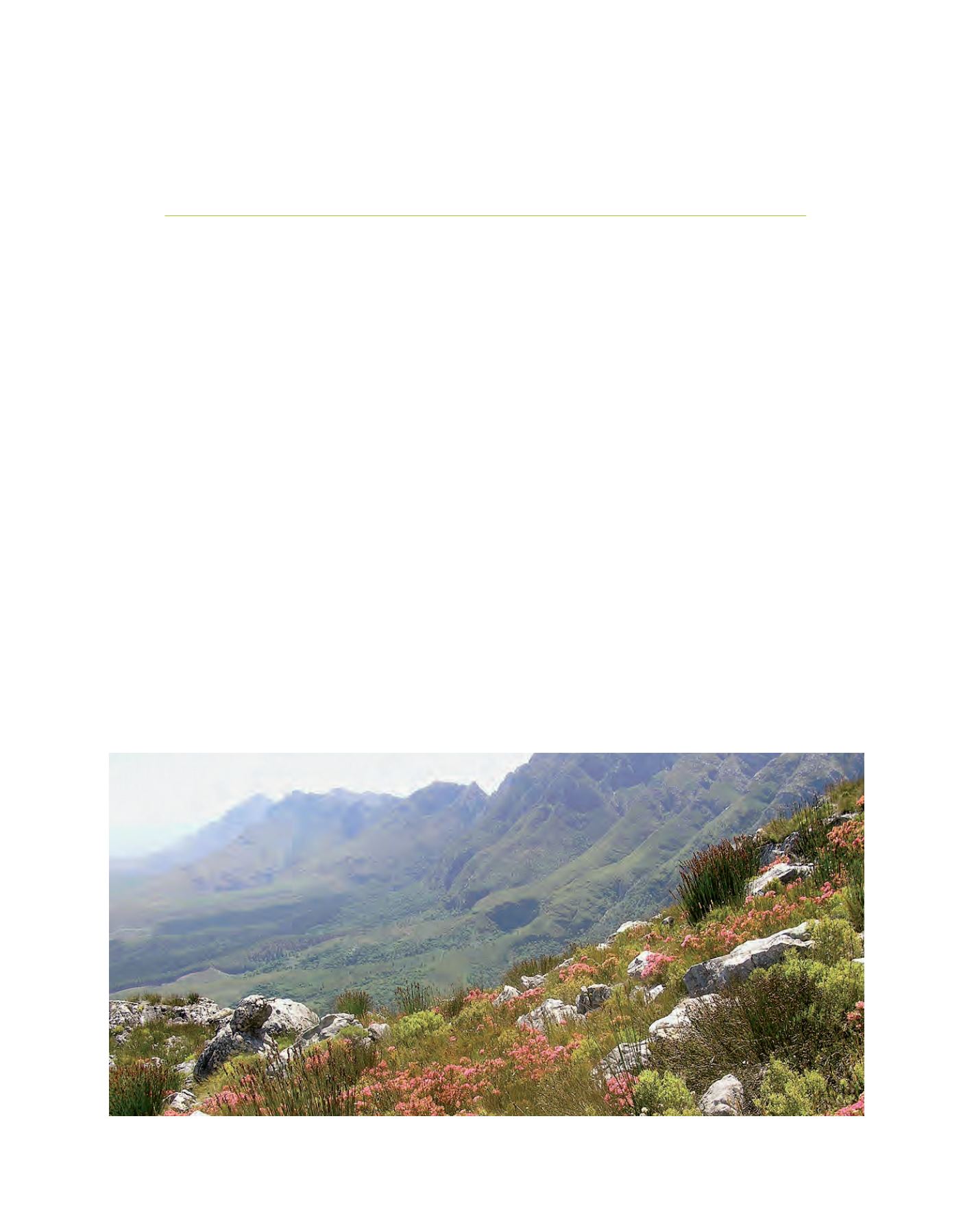

Fynbos vegetation in South Africa (foreground) being invaded by pines escaping from plantations (background)

Image: Tessa Oliver