[

] 104

G

overnance

and

P

olicy

Although the winning point for this programme is

its ability to provide employment, many other indirect

consequences of the programme improve people’s general

standard of living. South Africa’s targets to provide most of

the population with potable water and sanitation are reliant

on sufficient water resources. This is a challenge in a largely

arid country. Water that otherwise would be lost is now

available for agriculture, urban and industrial use. Clearly,

water saved from alien plants can contribute to ensuring a

better future for the people of South Africa.

Ironically, just as Working for Water was being

conceived, the monitoring that justified it was being shut

down in the early 1990s by the government forestry divi-

sion, who could see no further use in quantifying water-use

by plantations. Only the original weirs at Jonkershoek

continued to be monitored by the Council for Scientific

and Industrial Research. These faced closure in 2007 when

government funding ceased. The newly created South

African Environmental Observation Network, or SAEON,

stepped in to secure the monitoring whilst negotiations

were underfoot. Fortunately, a change of perspective in

decision-making circles has made the future of catchment

monitoring more secure. It has been recognized that flow

data is relevant far beyond commercial forestry, particu-

larly in understanding the relationships between rainfall

and runoff in a changing climate. In addition it is recog-

nized that if we are to understand the direction and nature

of climate change in a country where climate is naturally

highly variable, long-term records are essential. If we are

to ensure that water continues to play its social, economic

and ecological roles from source to its eventual sink in

our oceans, then an integrated monitoring and research

approach – moving away from narrow sectoral inter-

est – is needed. Adaptation to altered water delivery is

also highly dependent on understanding what happens to

water as it enters the cycle.

In international literature on public works the multi-

ple objectives of the South African Working for Water

programme have beendescribed as beingwithout precedent.

In biodiversity circles it is lauded as the largest environmen-

tal management programme in Africa. Among many policy

decision-making processes which impact people as well

as the environment, Working for Water stands out as one

where scientific evidence is evaluated, progress ismonitored

and assessed in both the biodiversity and social spheres and

new research is commissioned to ensure that decisions are

underpinned by as sound evidence as is available.

5

Yet in

the 1930s when the catchment monitoring programme was

launched, these outcomes could not have been foreseen.

This suggests that whilst monitoring programmes need to

be based on sound scientific reasoning, we should be open

to unintended results. We should also protect environmen-

tal monitoring programmes from the vagaries of narrow

and sectoral interests that may threaten their continued

existence. The challenges we face need interdisciplinary

approaches and, it can be argued that, support for environ-

mental monitoring programmes will be strengthened, and

their results be more broadly useful, if they are initiated in

partnership with people from different sectors.

supply infrastructure. If invasive plants are not kept in check it is likely

that they will double their stream flow reduction impacts in 15 years.

But could evidence that invasive plants used more water than

indigenous vegetation be sufficient to muster the kind of resources

needed to eradicate them? For several decades environmental volun-

teers and conservation agents had been clearing invasives with

limited resources and not much hope of making an impact.

In 1994, South Africa had its first democratic elections and with these

came hope that some intransigent problems could be solved. It took a

group of scientists convinced of the need for action based on the stream

flow evidence, a far-sighted government minister and a big dose of

serendipity to create a solution. If poverty alleviation could be linked to

invasive alien plant control then funding could be attained for clearing.

From this, the Working for Water programme was born in 1995.

3

Poverty, exacerbated by widespread lack of skills training, is

recognized as one of the biggest problems facing South Africa. Large

sectors of communities, including rural communities, face the pros-

pect of almost permanent unemployment. Those hardest hit by this

are women and young people, who with low education and no skills

struggle to enter employment.

Working for Water engages otherwise unemployed people to clear

invasive alien plants using an integrated approach of physical clearing,

chemical treatments and biocontrol to tackle the problem. From 30

projects in 1995, there are now 300 clearing projects. Almost 20,000

previously unemployed people are employed a year. Programmemanag-

ers aiming to meet targets to engage women, young people and disabled

people ensure that 53 per cent of those employed are women, 22 per

cent are young people and 0.6 per cent are disabled. Social development

programmes run parallel to the clearing programme. These are oper-

ated in partnership with other organizations and include establishing

childcare facilities for communities where Working for Water is active,

HIV and AIDS education programmes, and a programme to reintegrate

ex-offenders into the workplace, as well as training in clearing, restora-

tion and workplace health and safety issues. Training is also given in

business skills to develop contractors from disadvantaged communities

who thenmanage the clearing teams and, it is hoped, will be able to take

up private clearing contracts.

4

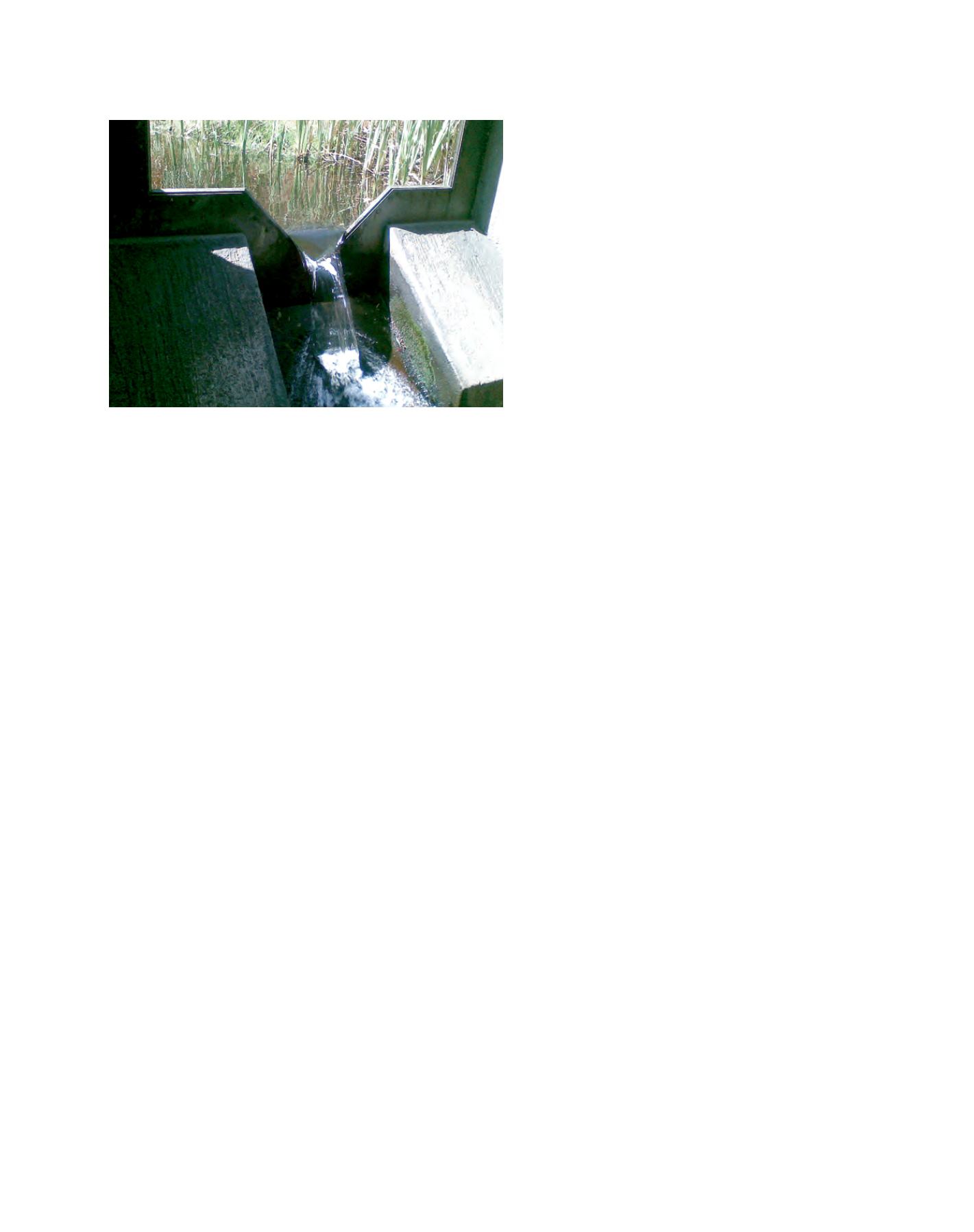

Run off from mountain catchments has been measured since 1937 with

continuously-recording stream flow gauges such as this one at Jonkershoek,

South Africa

Image: Nicky Allsopp