[

] 27

become essential elements to family reproduction and farm

units no longer depend solely on agriculture.

This conceptual shift has been crucial for changing the

ideas and conceptions of policymakers and scholars on family

farming. Such change has not only theoretical and conceptual

effects, but also political and ideological ones. It is increasingly

evident that family farming is not necessarily synonymous

with small-scale farming. For a long time – and still today

– small-scale farming has been considered poor, marginal

and inept, and thus was always on the verge of disappearing.

Many papers have made the case that peasants and all kinds

of small farmers were poor because they were small and thus

could not achieve great economic performance. Fortunately,

current discussions on family farming are overcoming this

bias. Family farming is seen increasingly less as synonymous

with poverty or aversion to markets and technology.

But there are other aspects to consider in this conceptual

evolution, which also represent novelties in relation to past

debates and understandings. The current debate on family

farming in Latin America and the Caribbean does not empha-

size the political and ideological aspects that marked the

discussions on peasants and their revolutionary potential in

the 1960s and 1970s. Likewise, the current analyses of family

farming go further in discussing the efficiency and/or effec-

tiveness of small-scale farming, or the persistence of small

farms within the capitalist dynamics of agribusiness chains,

which was a major issue during the 1980s and part of 1990s.

From this process of development and resumption of some

existing concepts emerges a broader view of family farming

in Latin America and the Caribbean, based on the notion that

family farming refers to the exercise of an economic activity

by a social group that is united by kinship and constitutes a

family.

3

Furthermore, the economic activity and the produc-

tion of goods, products and services is also a way of life that

involves all members of a family.

Family farming constitutes a particular form of labour and

production organization that exists and is reproduced within the

social and economic context where it is embedded. Its repro-

duction is determined by internal factors related to the way

of managing productive resources (such as land, capital and

technology), making investment and expenditure decisions, allo-

cating the work of family members and adhering to the cultural

values of the group they belong to. Yet, family farmers cannot

elude the social and economic context in which they live and by

which they are conditioned, or sometimes subjected to. Among

these determinants are increasing urban demands for both

healthy foods and the preservation of landscapes, soil, water and

biodiversity. Technological innovations are also determinants

that can reduce the role of both the land and the labour force in

the production processes. Thus, they can be decisive for greater

competitiveness of the productive units.

Characteristics of family farming

According to the latest report by the United Nations

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean,

FAO and the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on

Agriculture in 2013, it is estimated that the family farming

sector in Latin America amounts to nearly 17 million units,

comprising a population of about 60 million, and that 57

per cent of these units are located in South America. Despite

lacking precise figures for every country, family farming is

considered to represent 75 per cent of the total production

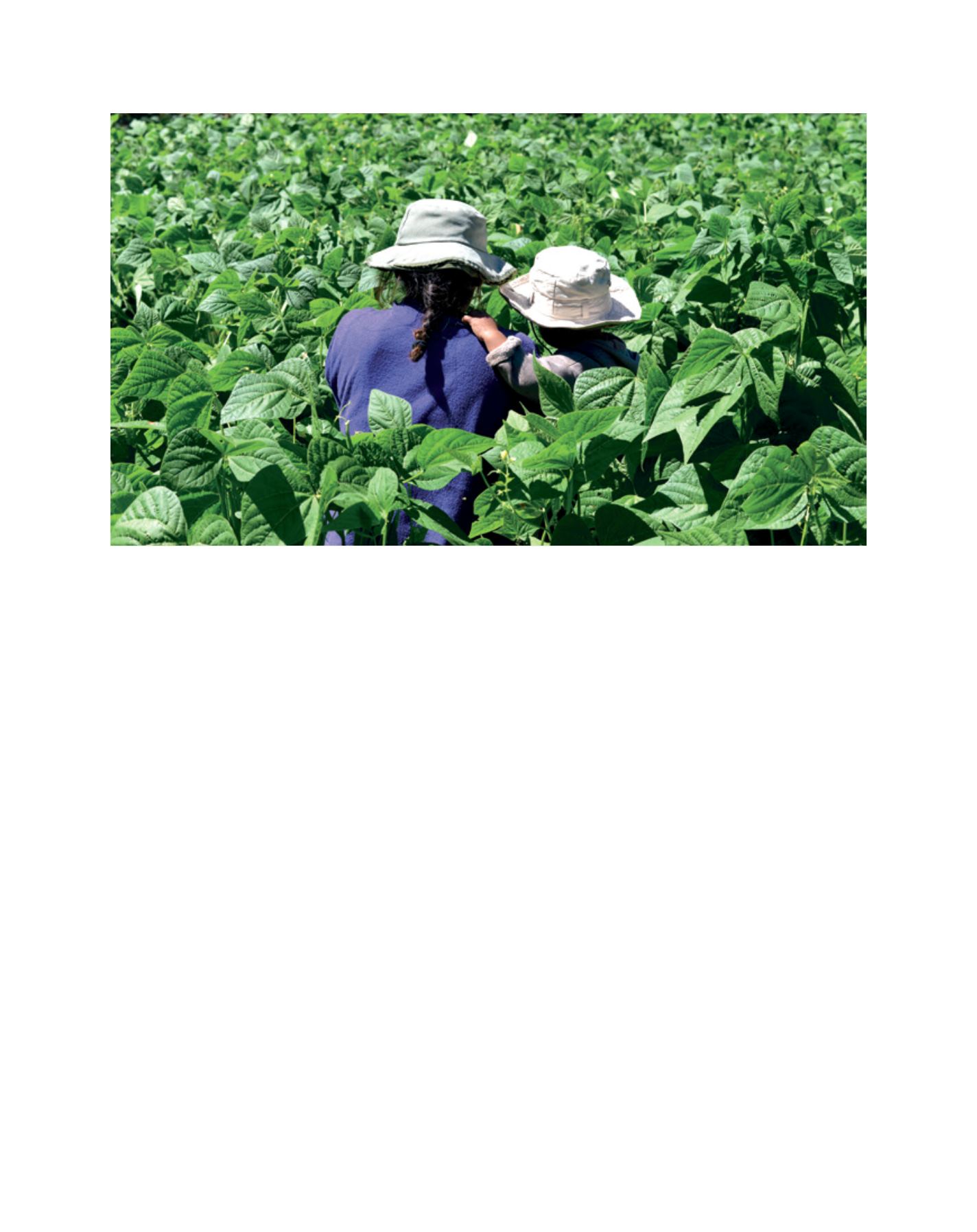

‘Stand by me’, Honduras (IYFF photo competition - North and Central America regional winner)

Image: Claudia Calder

R

egional

P

erspectives