[

] 31

food costs provide agricultural exports. Railroads were built to

encourage expansion of agricultural production for export.

The resulting social inequity, deprivation of access to farm-

land, and the exploitation of peasants and workers led to repeated

rebellions, which spawned the Mexican revolution of 1910,

leading to a new Constitution in 1917. The new constitution

authorized agrarian land reform. By 1940 most of the country’s

arable land had been redistributed to peasant farmers, benefitting

only approximately one-third of all Mexicans. However, declin-

ing productivity during 1980s, and mounting food imports gave

Mexican President Salinas, elected in 1988, political momentum

to reform the land tenure system. The following reconsolidation

of agricultural land into large corporate farms set the stage for

the North American Free Trade agreement of 1994 (NAFTA)

between Mexico, the US and Canada. As in the US and Canada,

family farms in Mexico are being consolidated into large farm

business intended to compete in global markets.

Challenges to family farmers

North American farm families today face a number of major chal-

lenges – some continuing and others new. Farm policies that

increasingly support the industrialization of farming in a quest

for economic efficiency have intensified with the implementation

of NAFTA. The increasing emphasis of farm policies on mono-

functional economic efficiency makes it even more difficult for

multifunctional family farms to survive economically while main-

taining their social and ethical commitments tomultifunctionality.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the focus of US farm policy

shifted from ensuring food security through preserving family

farms to food security through agricultural productivity. A more

efficient agriculture was intended to reduce food prices, making

adequate quantities of wholesome and nutritious food affordable

for everyone. The strategies of industrial agriculture are speciali-

zation, standardization and consolidation of control, which

inevitably leads to larger and fewer farms. Every major farm

programme in the US since the New Deal era of the 1930s, in

one way or another, has promoted agricultural industrialization

– thereby promoting consolidation of agricultural production

into fewer and larger economic production units.

As agricultural production expanded well beyond needs

for domestic consumption, farm policies shifted to expansion

of export markets. Farm policies in Canada today are largely

driven by international trade considerations. The emphasis on

international trade further narrows the focus of farm policies

on monofunctionality and economic efficiency. Thus, NAFTA

has severely affected multifunctional family farmers in all three

countries, especially inMexico, where the agreement accelerated

agricultural consolidation and industrialization, particularly in

the northern regions of the country.

Another major challenge to family farmers in North America is

the advancing age of farmers. Young people without farm back-

grounds have begun to operate small farms in the US and Canada,

but not enough to offset those leaving established farms. If current

trends continue, even more farms will become consolidated into

monofunctional farm businesses, leaving smaller multifunctional

family farms. Much of the knowledge and wisdom that will be

needed to sustain family farms resides in the hearts and minds

of today’s ageing farmers. Industrial agriculture dominates public

research and education, particularly the land-grant universities.

As a result, multifunctional family farmers have turned to learning

fromeach other. Unfortunately, when today’s ageing farmers retire

or die, their personal knowledge and wisdom will go with them.

Young people who do choose farming as their occupation

also face a major challenge in gaining access to land. Prices of

farmland are at record high levels in the US as a consequence

of expanding demand in global markets and domestic biofuel

subsidies andmandates. Government programmes for ‘beginning

farmers’ are targeted primarily to new commodity producers, not

new family farmers who produce for local markets. As much as

70 per cent of US farmland may change hands over the next two

decades.

5

Non-farm investors and large private equity investors

have become major competitors in farmland markets. Access to

farmland for family farmers is a challenge not likely to be met

without significant changes in land tenure policies.

Farmers traditionally have prided themselves on their inde-

pendence. This may have been an asset to family farms in the

past but it could be a major obstacle in the future. Today’s smaller

family farms that are producing for local niche markets will need

to scale up their operations. To meet this challenge, literally

thousands of farmer alliances, cooperatives, networks and food

hubs are being established all across the US and Canada.

6

These

new food networks must follow the organizational principles

of earlier cooperative organizations if they are to maintain their

multifunctionality and thus their sustainability. Those farmers

who meet the challenges of cooperation may well find it to be

one of the most economically and personally rewarding aspects

of family farming in the future.

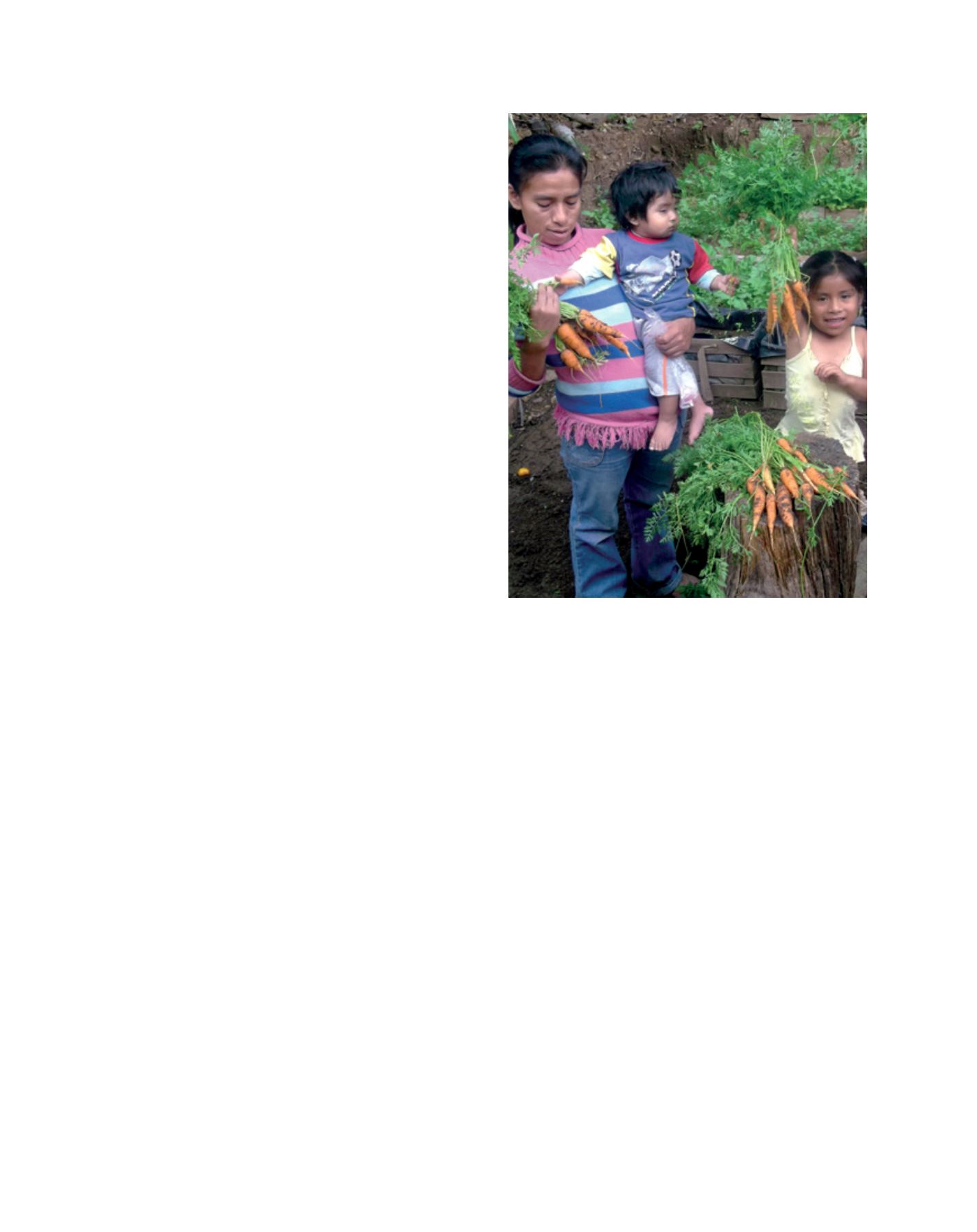

Family farmers in Mexico display the fruits of their labour

Image: Valentin Rivera Luna

R

egional

P

erspectives