[

] 23

to enhance and defend the interests of family farming has the

knock-on effect of jeopardizing rural well-being, nutrition and

education, or rural development more broadly defined.

War, economic reform and climate change

Since the Second World War, NENA has experienced the

highest number of international wars and civil conflict of any

region in the world, at an enormous human and economic

cost. That cost has serious implications for the undermin-

ing of vibrant and ecologically self-sustaining family farming.

War and conflict slashes gross domestic product (GDP), and

destroys lives and economic infrastructure.

Sudan is a low-income food deficit country – one of the

least-developed regions. Its long civil war in the South and in

Darfur, as well as a range of other persistent conflicts, have

lasting consequences that impact family farming and pasto-

ralism. Displacement of farmers, for example, has disrupted

farming and agropastoralism in Blue Nile and South Kordofan,

where more than 500,000 are food insecure.

Following the first Gulf War in 1990, Iraq lost two-thirds

of its GDP and the ensuing sanctions campaign took the

lives of 1.5 million including 500,000 children.

11

Sanctions

and war dramatically affected family farming, already under-

mined by Iraq’s dependence upon oil that accounts for up

to 60 per cent of the country’s GDP. Iraq had been a ‘bread

basket’, but by 1990 it imported 70 per cent of its cereals,

legumes, oils and sugar.

12

Disease, death and malnutrition

accelerated after the international sanctions regime that

followed Saddam’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait. This continued

during the ‘oil for food’ programme.

The Iraq war and internal violence that followed

US-led intervention crippled Iraq’s family farming sector,

further restricting agricultural production and marketing.

Reconstruction has focused on the oil sector and regional

spoils rather than investment in family farming.

In Syria the devastating civil war and outside intervention has

reduced the majority of people to hunger and starvation. And

conflict has been central to the history of Yemen, where almost

half of the 20 million population is food insecure. Conflict in

Yemen has continued since unification and the 2011 uprisings

for political liberalization and democratization.

The Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPTs) have been

the theatre of conflict, disruption and dislocation, and

violent dispossession of farmers, herders and agropastoral-

ists, with the result that small farmer agriculture in the OPTs

is the most undermined in the region. The conflicts in Gaza

in 2008-2009, 2012 and 2014 caused dramatic constraints

on family farming. For instance, according to the Food and

Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2008-2009, “almost all of

Gaza’s 10,000 smallholder farms suffered damage and many

[were] completely destroyed, having a severe impact on liveli-

hoods,”

13

and in 2012 alone, there was a “twofold increase in

the destruction of agricultural assets, such as olive and fruit

trees and cisterns – and with it lost income.”

14

Palestinians are

also a microcosm of the region’s predominantly young popula-

tion. Almost 65 per cent of Palestinians are less than 24 years

old and in the NENA region as a whole there are more than

100 million between the ages of 15 and 29. With regionally

declining population growth rates the young offer a strong and

important ‘demographic dividend’.

15

A predominantly young

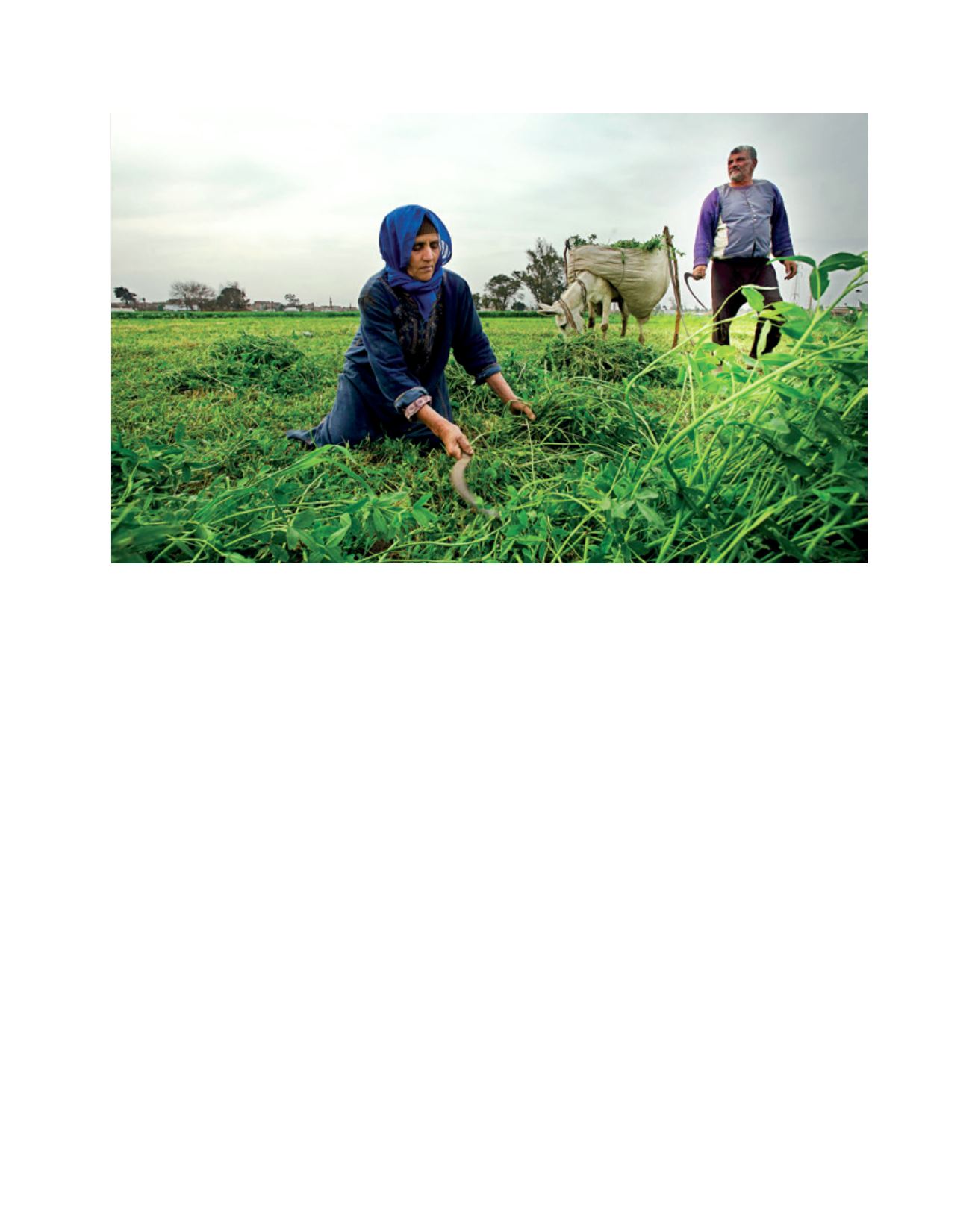

Haji Bakri Mohammed and his mother cultivate their land

Image: Abdelkader Eisayed

R

egional

P

erspectives