[

] 18

largely enclaves producing tropical crops and permanent trees for

export. Consequently, family farms are reproduced (or survive)

within a historical context of struggle against larger-scale capital-

ized farming and land alienation.

Small-scale farmers have generally been pejoratively perceived

and labelled by many policy experts and scholars as ‘traditional’

or ‘backward’, ‘subsistence farmers’, inferior to technologically

progressive profit-oriented LSCFs, linked to financial inputs and

commodity markets. They are often wrongly called ‘communal

farmers’ working collectively on commonly held land without

secure tenure. The failure of SSA to achieve globally comparable

agricultural productivity levels tends to be attributed to various

alleged maladies considered inherent in family farming systems,

including land tenure insecurity, subsistence orientation and the

presumed absence of production and market economies of scale.

Family farms are multifunctional production and consump-

tion units, which meet a range of their consumption and

income needs. Their production is structured around indi-

vidual family and/or household-owned fields (often including

extended family members), while their livestock rearing (of

family-owned herds) and natural resource management

activities are mostly undertaken conjointly on common

lands. Family farm members work together on their arable

plots and in tending to their livestock. Most family farms in

sub-tropical SSA practise mixed crop and livestock farming.

While most family farms do not own cattle, large family farm

populations in Eastern and West Africa predominantly prac-

tise pastoralism. Generally, family farms have common access

to community-owned natural resource reserves, and tend to

pursue ecologically sensitive management practices regard-

ing their use and reproduction of land and natural resources.

Diversity and heterogeneity

The scale and organizational forms, as well as the production

focus of family farming in SSA, have mutated significantly

since independence due to other structural changes, includ-

ing rapid demographic growth and urbanization, snail-paced

technical shifts in agriculture, new forms of urban demand for

food and their increased market integration. Moreover, family

farms are stratified according to various social hierarchies

derived from organic tendencies to economic differentiation,

territorial and social heterogeneity, and social identity differ-

ences such as gender, generation, race and ethnicity.

A heterogeneous range of family farms operate under the

diverse agroecological, conditions of SSA based upon histori-

cally specific patterns of political and economic transformation

shaped by the variegated incorporation of the region into world

markets, over the last century.

4

What is relatively unique about

the resilience of family farms in SSA is that their predominance

is derived from the persistence of household-lineage based land

tenure relations, despite various waves of land alienation which

began at the dawn of the nineteenth century,

5

and continue to

date.

6

A

priori

family farms have access to land largely through

allocations and inheritance rules governed by customary proce-

dures, although access increasingly occurs through various

forms of land rentals, sharecropping and informal land sales

(and livestock keeping arrangements).

It is estimated that there are over 100million family farms in the

44 countries of SSA. Their numerical growth is largely in conso-

nance with the changing density of the region’s rural population,

particularly those active in agriculture. While the proportion of

SSA’s rural population fell from 84.5 per cent in 1961 to 62.4 per

cent in 2013, the absolute number rose substantially from 188.4

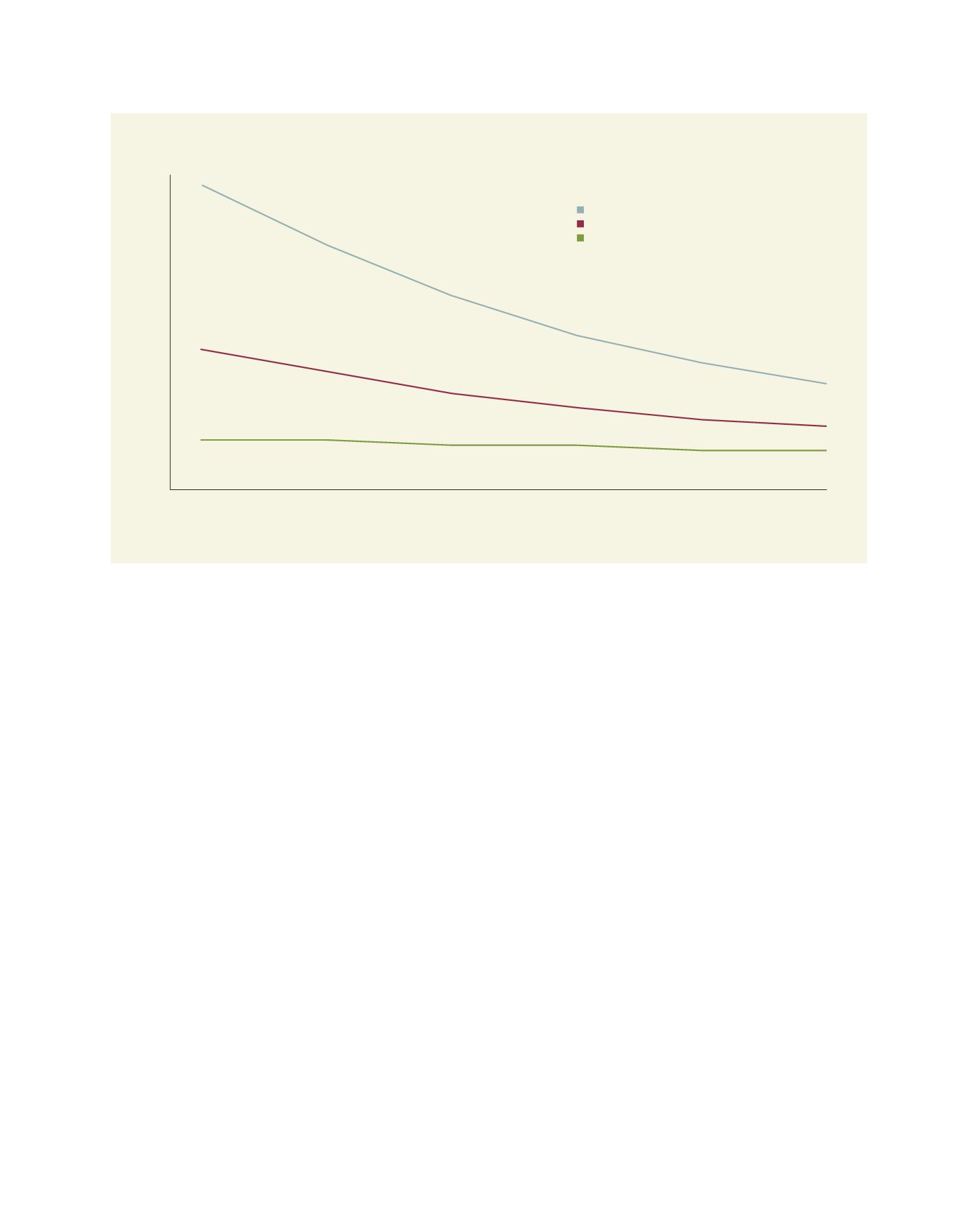

Total land area per capita in SSA

Source: FAO STAT 2014

1960

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Area per capita (Ha/person)

1970

1980

1990

2000

2010

Agricultural area per capita

Arable land per capita

Land area per capita

R

egional

P

erspectives