[

] 19

million to 562 million. This means that the number of families

dependent on farming may have trebled since 1961.

A fundamental factor which differentiates family farms from

LSCFs is that they use less hired labour. Most family farms hire

out their labour, while a few hire in labour from various sources,

and some do neither. Furthermore, family farms tend to be differ-

entiated according to the relative sizes of landholdings and levels

of capitalization (for example mechanization, irrigation) which

influence their operational scale and labour intensity. Such differ-

entiation is reflected in the varied levels of cropped areas and/

or livestock holdings, productivity and output (including food

surpluses) realized. While most contemporary family farms sell

a portion of their produce, some sell more than others. However,

fewer family farms obtain external finances (through various

credit circuits, contracts and remittances) to procure inputs and

implements and market their produce.

The spectrum of family farms therefore ranges at the top end

from the ‘better-off’ family farm (sometimes called the ‘rich’ or

‘capitalist’ family farm) that employs more hired labour than

family labour power and sells larger quantities of produce to

markets. These are often also referred to as market-oriented

family farms, living well above the poverty line.

7

At the bottom

end is the ‘poor’(near landless, semi-proletarian) family farm

that largely sells its labour to other farm and non-farm entities,

and hardly produces enough to meet family food requirements,

let alone to sell to markets. These family farms fall below

the poverty line and are at times labour-constrained family

farms,

8

often because of itinerancy of family members and/or

other social deprivations (such as the effects of HIV-AIDS). In

between is the middle or ‘semi-subsistence’ family farm. This is

the only category that has the semblance of an ideal-type family

farm which neither hires nor sells labour power, but produces

most of its food requirements and sells some produce to meet

a range of family needs.

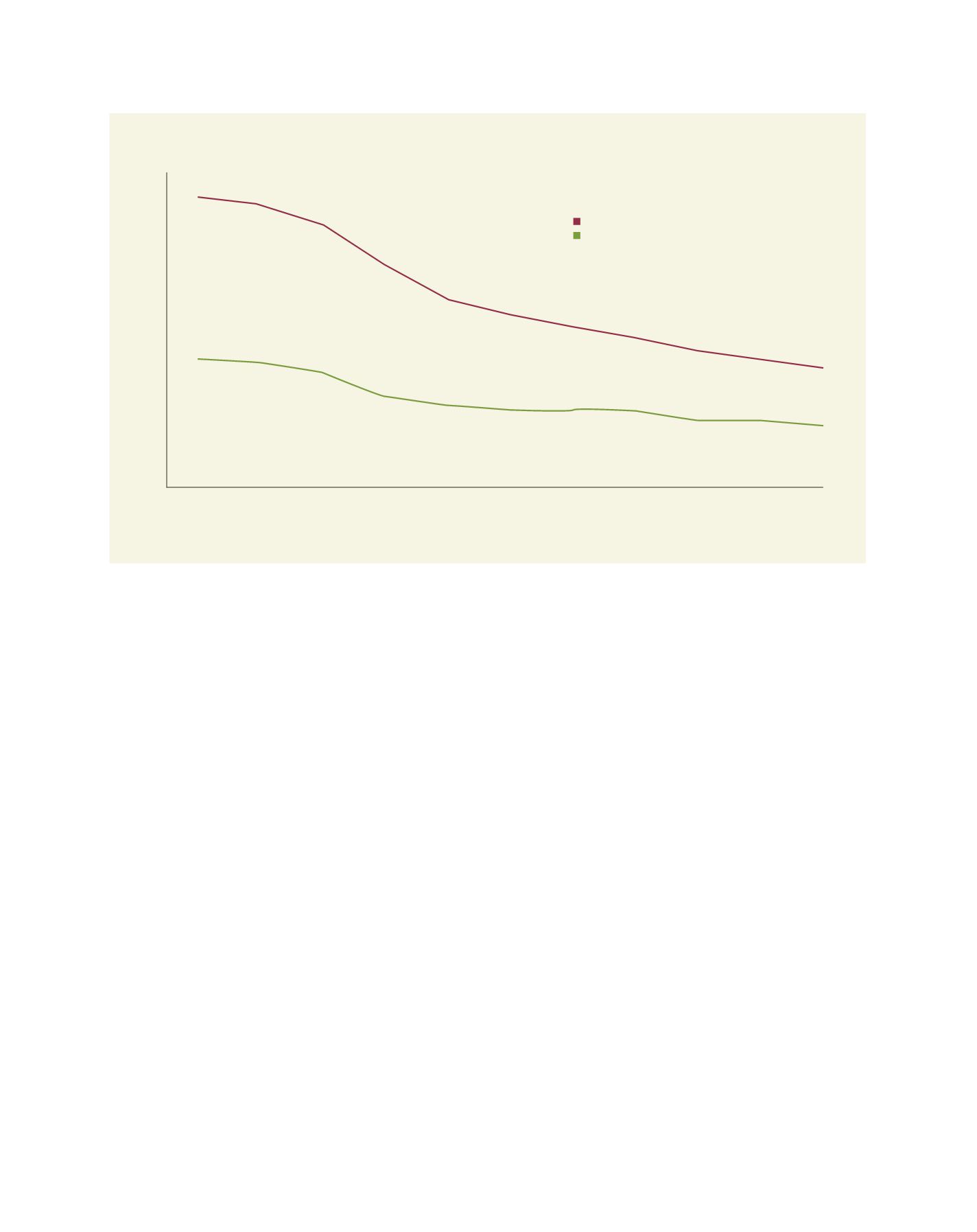

Access to arable land is decisive in defining the inci-

dence and scope of family farm producers, as well as their

basic reproduction and survival. The constraints imposed

by increasing arable land scarcity and inequitable access to

the limited available arable land are important in shaping the

diversity of family farms. The rapid decline in arable land per

capita means that unless there is a demographic transition,

whereby rural population growth slows down more quickly or

there is increased farm productivity, the availability of arable

land for new family farms can be expected to end by 2030.

The combination of land and other forms of capital and labour

within family farms is not spread evenly within a single house-

hold, as it also tends to be differentiated according to gender

and generation. Generally, the patriarchs control the means of

production while women and children mainly provide largely

unwaged labour, and the management of family farms is largely

divided by gender, withmen being dominant in decision-making.

The marginalization of women in access to and control of family

land and farming resources remains an increasingly recognized

impediment to the development of family farms.

The classification of family farms according to their market

integration and/or cash cropping is commonly used through-

out SSA. In West Africa, the most commonly observed

categories include market oriented family farms with a cash

crop specialization, family farms which balance cereal and

cash crop production, and those with only subsistence cereal

holdings.

9

In Kenya and Uganda, family farms which rely

on permanent off-farm employment are distinguished from

Arable land and cropped area per capita in SSA

Source: FAO STAT 2014

1960

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

Area per capita (Ha/person)

1970

1980

1990

2000

2010

Arable land per capita

Cropped area per capita

R

egional

P

erspectives