[

] 13

family farmland, family labour and self-supplied capital for

household reproduction and subsistence. Its dependence

on, and involvement in, external markets for productive

factors (such as land, capital, labour and inputs) is partial.

Extended from the broader classification of family farming

in terms of political economy, eight features elaborate the

nature and quality of family farming more specifically:

• subsistence and livelihood satisfaction

• family centrality

• labour intensification

• diversification, pluriactivity and risk reduction

• autonomy and deliberation of market integration

• endogeneity and locality

• food sovereignty and food safety

• environmentally friendly with cultural heritage.

With the above features, family farming contributes greatly

to food sovereignty and food safety. It safeguards food secu-

rity for producers, especially marginalized peasants and the

poor; localizes food systems; renders control and autonomy

to local people; builds knowledge and skills; and works

with nature. It implies the rights of small-scale family

farmers to access agricultural resources. The feature of food

sovereignty is particularly important under the global food

regime and large-scale land acquisition processes, which

have been labelled ‘land grabbing’.

In the context of Asia and the Pacific, family farming

faces dramatic challenges under global capitalization and

agrarian transition. The transition from family farming to

large-scale, capitalized farming occurs in the developing

countries of Asia and the Pacific are involved in capitaliza-

tion through contract farming. Compared to the income

increase brought by contract farming, the loss of social

standing and political power over their own land and

labour, the increased social differentiation and disintegra-

tion of rural communities, and the rising inequality and

risks of landlessness represent immeasurable impacts for

family farming and rural society as a whole. The second

significant challenge comes from land-grabbing, both by

global players and domestic development. According to

the Land Matrix, Asia is second to Africa in terms of the

number of hectares affected by land deals. Land-grabbing

is not just about physical dispossession but a broader sense

of dispossession. Evidence shows that land acquisition

and the displacement of family farmers has had negative

effects on ecological systems, food security, family farmers

and rural dwellers as a whole. The third major challenge

for family farming is the deagrarianization of rural youth

in the trend of migration. It is necessary to envisage the

downside of migration on family farming. At the house-

hold and individual level, the most notable change after

labour migration is the increasing involvement of women,

children and the elderly in farming and the transition from

labour-intensive farming to fast farming. For agriculture

production, the deagrarianization of rural youth and the

ageing of the farming population have already significantly

weakened agriculture and family farming.

Family farmers contribute to local market development,

community-level cooperation and resilience, and ultimately

to countries’ gross domestic product. They have important

roles and contributions in enhancing the multifunctionality

of agriculture, such as preserving local traditions, heritage

and food systems as well as community ecosystems and rural

landscapes. However, such an important role can hardly be

realized without all-round recognition and external support.

The understanding and perception of family farming is

closely related to views on agriculture and development. For

Asia and the Pacific, generally being a developing region,

most developing countries in this region have embraced

the developmental paths of industrialization, urbanization

and marketization – in a word, a Western ‘modernization’

set by Europe and North America. Since the 1980s, agri-

culture in Asian countries has been actively integrated into

global markets. The forces of globalization, deregulation

and withdrawal of government from agriculture, the liber-

alization of agricultural sectors, the privatization of services

and information, structural adjustment, international trade

agreements and new technologies, create an ambiguous

environment for policymaking. Policymaking to defend and

support family farming should:

• protect agriculture as public goods rather than

throwing it into the market

• consolidate the centrality of family farming, protecting

peasants from land-grabbing and proletarianization

• emphasize peasants’ food sovereignty and its

contribution to global food security

• construct new and decentralized markets for

facilitating food safety

• facilitate reconstruction and comprehensive rural

development for the continuity of family farming

• acknowledge the multiple values of agriculture, recognizing

and boosting the values of traditional agriculture.

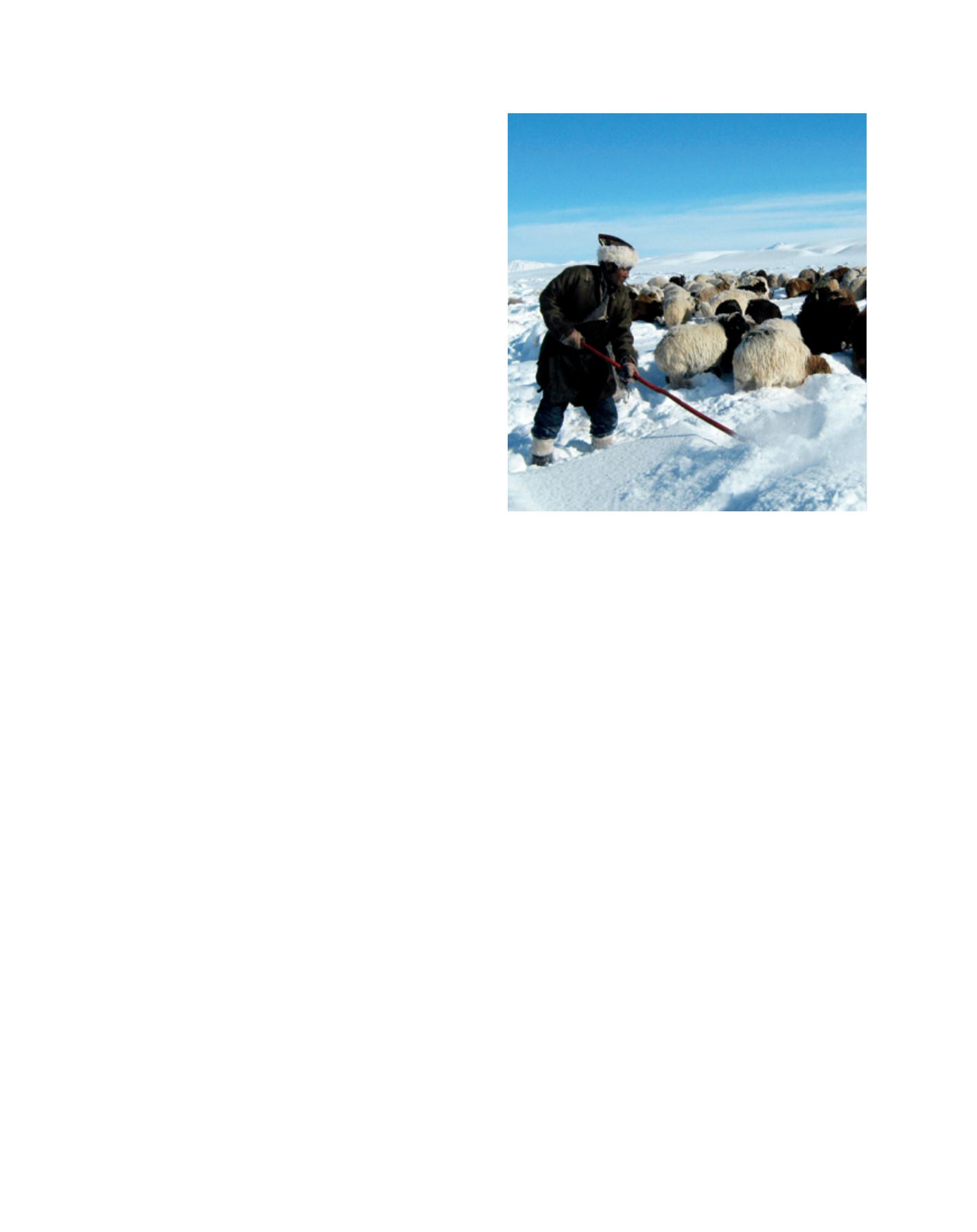

Dzud (the falling of big snow) is a major challenge for pastoralist families

Image: Erdenebileg Ulgiit

R

egional

P

erspectives