While the phone network is highly controlled and generally

static in terms of new countries, Internet networks may come

and go in rapid succession, extend or alter their connectivity,

partition or merge their operations – all of this on a daily basis

– and all without centralized control.

What is a domain name?

For Internet users, the most familiar forms of addresses are e-mail

and Web addresses and the word-based domain names that

appear within them. However, these are quite different from IP

addresses. While humans may prefer names, the machines that

make up the Internet need numbers. Thus, the purpose of the

Domain Naming System (DNS) is to allow Internet services to be

referenced by their domain name.

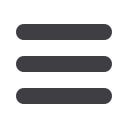

The DNS comprises thousands of servers across the Internet.

As Figure 1 shows, the DNS operates in a three-step process.

Typically, a computer may query the DNS about a particular name

(for example

www.google.com); the DNS server will provide the

IP address that corresponds to that domain name (in this

example, 66.102.7.104). From there the computer and the remote

service can communicate directly.

While IP addresses are fundamental to the operation of the

Internet infrastructure, the DNS is, in fact, a service which oper-

ates on the Internet. Although the DNS is an essential service in

today’s Internet, it could be removed or replaced without the need

for changes to the underlying infrastructure. In fact, even if the

entire DNS suffered a catastrophic breakdown, it would still be

possible to connect to any service on the Internet, provided its IP

address is known.

IP addresses management

The Internet started life as an academic and research network,

linking a close community of collaborating organizations and

institutions. Although the early pioneers had no way of predict-

ing the speed and spread of their creation’s growth, they created

an environment that allowed for outrageous success.

A fundamental principle of Internet design is that it is a layered

network that is ‘dumb’ at its core. Network A does not need to

know how Network B is configured in order to talk to it; and

whether it connects by copper wire, optical fibre, radio waves, or

any other infrastructure is irrelevant. So long as a network is

capable of transmitting data according to the standard protocols

(such as TCP/IP) it can become part of the Internet. It is not the

equipment that defines the Internet, but the protocols by which

communication takes place. A key aspect of those protocols is

the system of Internet addressing. Therefore, stable management

of the address system is vital to the success of the Internet.

The early model of address management

Recognising the importance of the Internet’s addressing system,

its founders established a central registry from the outset. The

most basic function of an address registry is to ensure unique-

ness of addresses, so that clashes cannot occur. Originally, this

registry was just one man – the late Jon Postel – using manual

processes to keep track of the addresses allocated to the then

small number of participating networks. The address registry

function became known as the Internet Assigned Numbers

Authority (IANA).

It is easy to forget just how quickly the Internet has grown in

the past decade, but even throughout the 1980s the available

addressing pool seemed vast. The registration function was

straightforward and the allocation mechanisms remained rela-

tively informal. However, as more networks joined the Internet

and growth began to accelerate, it became increasingly clear that

the original address management function would not scale.

The volume of requests, the linguistic and cultural diversity

of requestors, and the complexity of differing regional needs

caused a re-evaluation of the central registry model. In 1992,

the Internet Activities Board of the IETF considered these factors

and concluded: “…it is desirable to consider delegating the

registration function to an organization in each of [the]

geographic areas.” (RFC 1366, 1992)

Another major problem with early address management was

that the address technology was based on a crude subdivision of

the IPv4 address space into three network “classes”, allowing

only three potential address allocation sizes, namely: “Class C”

(256 addresses), “Class B” (65,534), or “Class A” (16,777,214).

By 1993, a new system had been introduced to eliminate the

wasteful practices of “classful” addressing, but even so it was clear

that the address pool could no longer be regarded as limitless.

[

] 186

DNS

My computer

www.google.com?

1

68.102.7.104

2

68.102.7.104

(www.google.com)3

The

Internet

Figure 1: By a three-step process, DNS provides access to a web site,

using a domain name

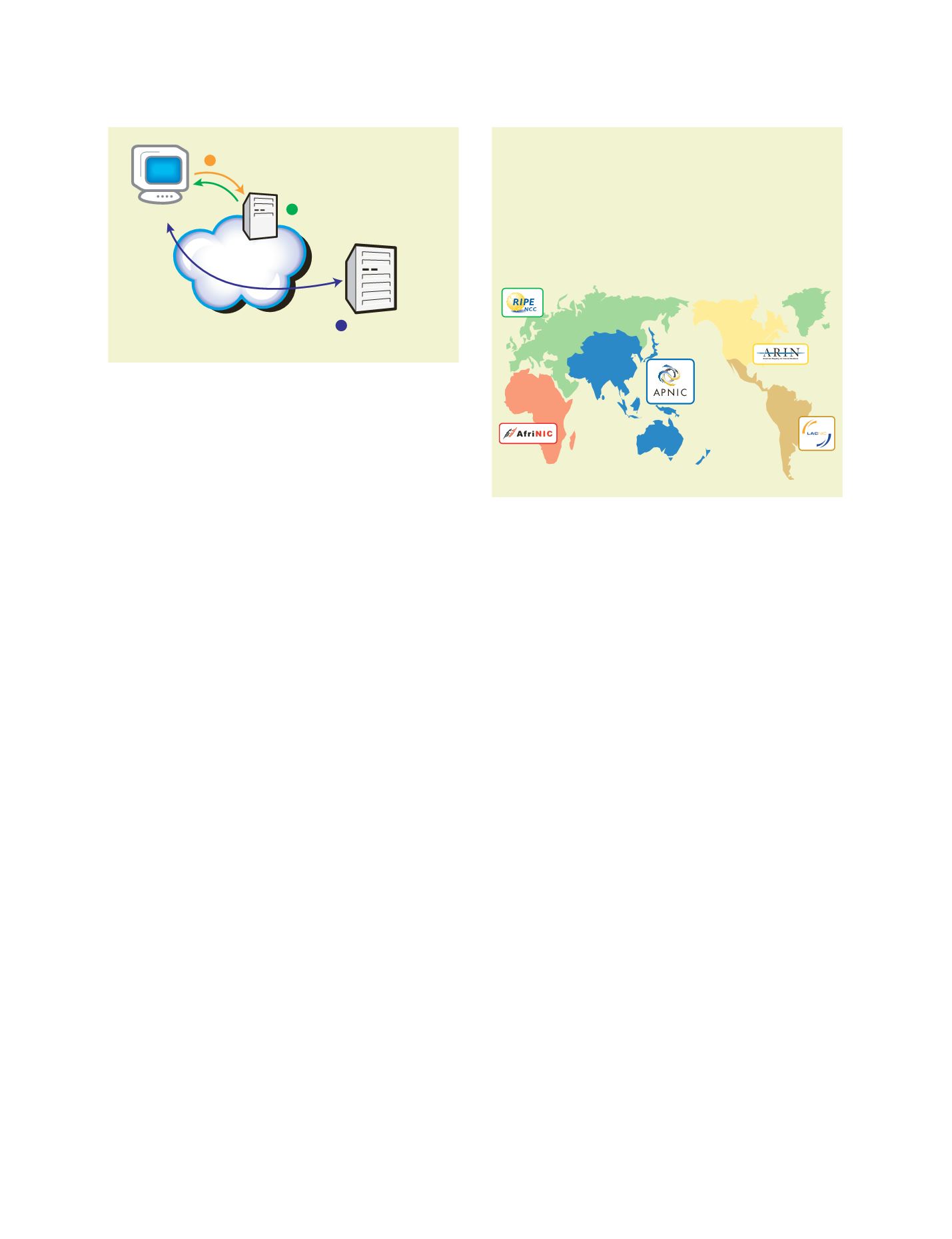

Figure 2: Address resources are managed by the five RIRs, under

policies developed by their respective regional communities

Registry

Region

AfriNIC

Africa

APNIC

Asia Pacific

ARIN

Canada, United States, several islands in the

Caribbean Sea & North Atlantic Ocean

LACNIC

Latin America, Caribbean

RIPE NCC

Europe, the Middle East, parts of Central Asia