[

] 177

Forests and forestry in Denmark –

thousands of years of interaction

between man and nature

Christian Lundmark Jensen, Coordinator on International Forest Policy,

Nature Planning and Biodiversity, Danish Ministry of the Environment Nature Agency

L

ife can only be understood backwards; but it must be

lived forwards,” said the famous Danish philosopher

Søren Kierkegaard back in 1843. Another old adage

says: “He who does not know the past, does not understand the

present and can not see into the future”. Both sentiments should

fit well to the story about forests and man in Denmark.

Natural expansion of the forest

Although the oldest traces of trees date back to the age of Jura

some 150 to 180 million years ago, numerous ice ages subsequently

coming and going have frequently cleared the Danish landscape of

practically all types of vegetation.

Since the last ice age, which ended around 13,000 years ago, forest

trees have immigrated successively. The pattern has been traditional,

with various primarily light-demanding species coming in first (such

as birch, aspen and pine) followed by more shade-tolerant types, at first

dominated by hazel. Subsequently species like oak, elm, alder and lime

arrived – and at a later stage, some 3,000-4,000 years ago, also beech.

It is assumed that at the peak of its succession, forest

covered the vast majority of the country, perhaps up to

80 per cent or more.

Harmony, degradation and deforestation

Human beings took part in the development of forests

and landscapes from the beginning. They quickly

settled at the coasts and sustained their livelihoods

through fishing, hunting and the collection of mush-

rooms, berries and nuts. The utilization rate was not

high, however, and certainly no threat to the forest.

The influence of man picked up speed with the intro-

duction of agriculture, approximately 6,000 years ago.

Hunter-gatherers were gradually replaced by farmers,

who introduced animal husbandry and used axe and

fire to clear land for crops.

Gradually the increasing population and economic

development caused further pressure on the forests.

This was brutally interrupted around the year 1300,

when the Black Death (plague) raged throughout

Europe, and killed almost a third of Denmark’s popu-

lation. However, after the Black Death, the picture

changed again and the forest came under renewed

pressure. It was now used for an increasing number

of different purposes, providing nuts, berries, apples

and game, hay and grazing for horses and cattle, and

beech mast for the fattening of pigs. The timber was

used for house building, stables and ships, tools, clogs

and pools. In addition, and not least, wood was used for

energy – for heating, salt sizzling, baking of tiles and

melting of iron.

All of it contributed to overexploitation, degradation

and deforestation. A significant contributing factor

was the special arrangements for ownership and use

rights. The system gave ownership and use rights for

squires and lords of manor to the mature stands of

high-boled trees, whilst the use rights for the under-

brush were given to tenants. Although intending the

opposite (protection of high-boled stands), the system

instead encouraged usage patterns among the tenants

that rarely allowed any young trees to fully develop

into maturity. Extensive grazing and coppice methods

prevented the forest from regenerating itself.

“

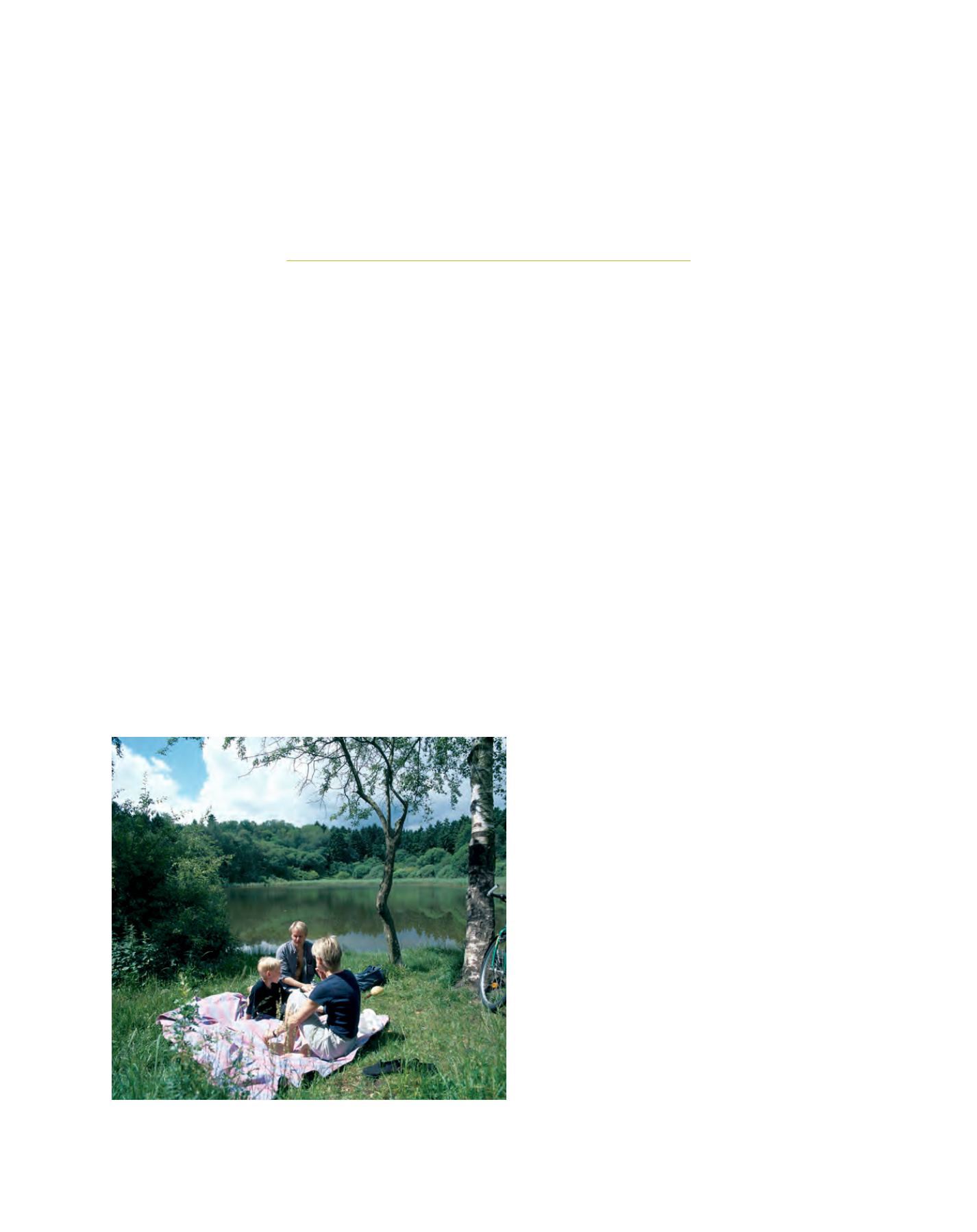

Danish forests are highly appreciated for outdoor life and recreation. Here, a family is

having a picnic lunch after a bicycle ride in the public forest Poulstrup

Image: ©Bert Wiklund