[

] 178

Thirdly, afforestation was promoted. It began at slow

rates, led by state planting activities, and was rapidly

increased by the late 1860s. Various factors triggered

this. One of these was the bitter loss of one third of the

country’s land area to Preussen and Austria in the war in

1864. Using the slogan “What is outwardly lost must be

inwardly won”, the Danish patriot and enthusiastic agita-

tor Enrico Mylius Dalgas managed to turn afforestation

into a national movement with broad public support.

The positive will was underpinned by public grants and

a general belief in the positive contribution of timber

production to the economic development, benefiting

both the landowners and society as a whole.

A large share of the afforestation was allocated along-

side the coastline in order to mitigate sand drift, in

particular in the western parts of Jutland. In the 1930s,

during the recession, afforestation was also welcomed

as a good means of job creation. It was promoted and

remained high until the 1960s, when high employment

rates and a booming agriculture industry slowed down

afforestation activities again.

Fourthly, but not least, the replacement of timber

with coal as the main energy source did unquestion-

ably help reduce the pressure on the forests during the

industrial revolution in the late 18th and early 19th

century. According to some historians this might have

been the most significant factor of them all.

A new era in 1989 – long-term goal to double

forest cover

In 1989 new visions, new measures and new regulatory

mechanisms were introduced, both for forest manage-

ment and for afforestation.

Around the year 1600, the forest cover was reduced to 20-25 per

cent. It dropped further down to 8-10 per cent in 1750 and reached

a low of only 2-4 per cent around 1800.

Apart from running short of timber and non-timber forest, parts

of the country now also suffered severely under storms and sand

drift. Crops and fertile agricultural lands could be buried in thick

layers of sand overnight, thereby destroying decades of hard work

by farmers.

Evidently, the situation had become out of control and there was

a growing understanding of the need for radical change.

200 years of recovery

Four major changes have paved the way for a slow, but steady recov-

ery of the Danish forests:

Firstly, a new regulatory mechanism for forest management and

use was adopted in 1805. The key elements included a new division

of ownership and use rights. They were now given to one party

only, not split between different groups. The squires and lords of

manor got the rights to the best forests, whilst rights to own and

use the poorer, low quality forests were given to the former tenants.

In addition, grazing in forests was abandoned and – not least – the

principle of permanent protection of classified forest reserves was

established. It applied to the majority of forest land at the time and

prevented conversion of forests to other land uses. To this very day,

this key principle has remained the backbone of Danish forest legis-

lation. The Forest Act of 1805 also established that forests had to

be properly managed, with a view first and foremost to securing the

long-term production of timber.

Secondly, forest management systems were introduced and

promoted, with assistance of the then highly acknowledged German

forestry expert, Johan Georg von Langen. He introduced systematic

replanting after clear cuts and the introduction of a number of high-

yielding exotic species.

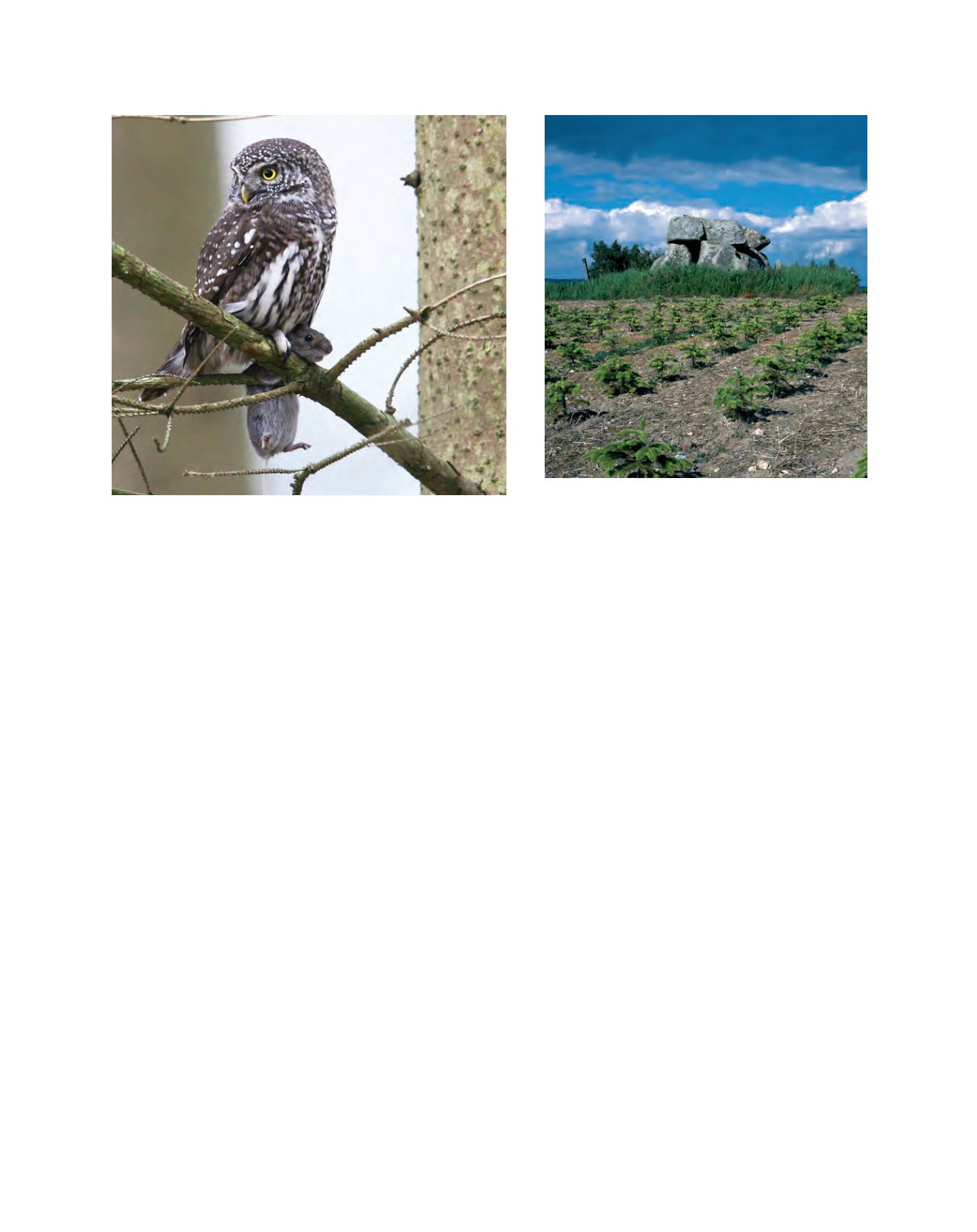

Biodiversity conservation is a key priority in the Danish NFP. Eurasian Pygmy Owl

(

Glaucidium passerinum

) seen resting after a successful mouse hunt in “Rude Forest”

A plantation of exotic conifers cultivated for the production of

Christmas trees – a popular and economically high-yielding

production both within and outside forest areas in Denmark

Image: ©Nis Lundmark Jensen

Image: ©Bert Wiklund