[

] 217

Voices of the forest:

building partnerships for

community forestry in Cambodia

Prabha Chandran, RECOFTC – The Center for People and Forests

W

e’ve depended on the forest for many generations.

If we don’t have legal rights, the forest will be lost.

Before we signed the [community forest] agreement,

we were always afraid that someone would take the trees and

destroy the forest. It took us almost three years, but the agree-

ment we have now means nobody can change the area and

outsiders cannot invest and take away our forest. We can keep

using it as we have traditionally.” (Mr Sorn Yam, Chairperson,

Community Forest Management Committee, Kbal O KraNhak,

Kampong Thom, Cambodia)

It’s a fight that’s been fought by local communities living in and

around forests across the world and it’s becoming more urgent as

rapid urbanization, compounded by food and fuel shortages, puts

daily pressure on forests. Yet, as the villagers of Kbal O KraNhak

discovered, it was possible to reclaim forests and assert

traditional rights – but only after a logging concession

had virtually destroyed their habitat. From 1996 their

forest lands were controlled by a logging company,

whose licence was revoked in 2001 following wide-

spread illegal activities. By then, the forest had been

largely destroyed and along with it, the livelihoods of

those in Kampong Thom – especially their traditional

trade of resin collection.

An environmental, social and economic disaster

On a national scale, more than half of Cambodia’s forest

land, nearly 7 million out of 10.8 million hectares,

was licensed to 33 companies via logging concessions

in the 1990s. The government believed these conces-

sions would generate much-needed revenues of US$100

million annually. Instead, by 1997, it was estimated that

four million cubic metres of illegal timber was pilfered

each year – ten times what could be taken sustainably –

causing a loss of US$60 million to the national treasury.

1

One of the poorest countries in the region, Cambodia

was recovering from almost three decades of civil war

and social upheaval. Poor governance, weak institu-

tions and law enforcement following the Khmer Rouge’s

exploitive policies had decimated the country’s primary

rainforest cover from 70 per cent in 1969 to 31 per cent,

in less than 40 years

2

. The conclusion from a number of

reviews

3

was that Government control of logging opera-

tions was ineffectual and might jeopardize long-term

economic growth and poverty reduction.

In response, the Government of Cambodia declared a

logging moratorium in 2002. However, economic growth

continues to draw heavily on the country’s natural

resources with investment in large-scale agriculture and

rubber plantations posing a growing threat. The loss of

forest cover has also exacerbated the poverty of millions

of rural families like Mr Sorn Yams’, who depend on local

forests for food, medicine, shelter and fuelwood.

Research shows that nearly half of Cambodia’s rural

households – more than five million people – rely

on forests for 20-50 per cent of their livelihood. For

another one million people, forests provide over half

of their livelihood.

4

Faced with a critical situation at

“

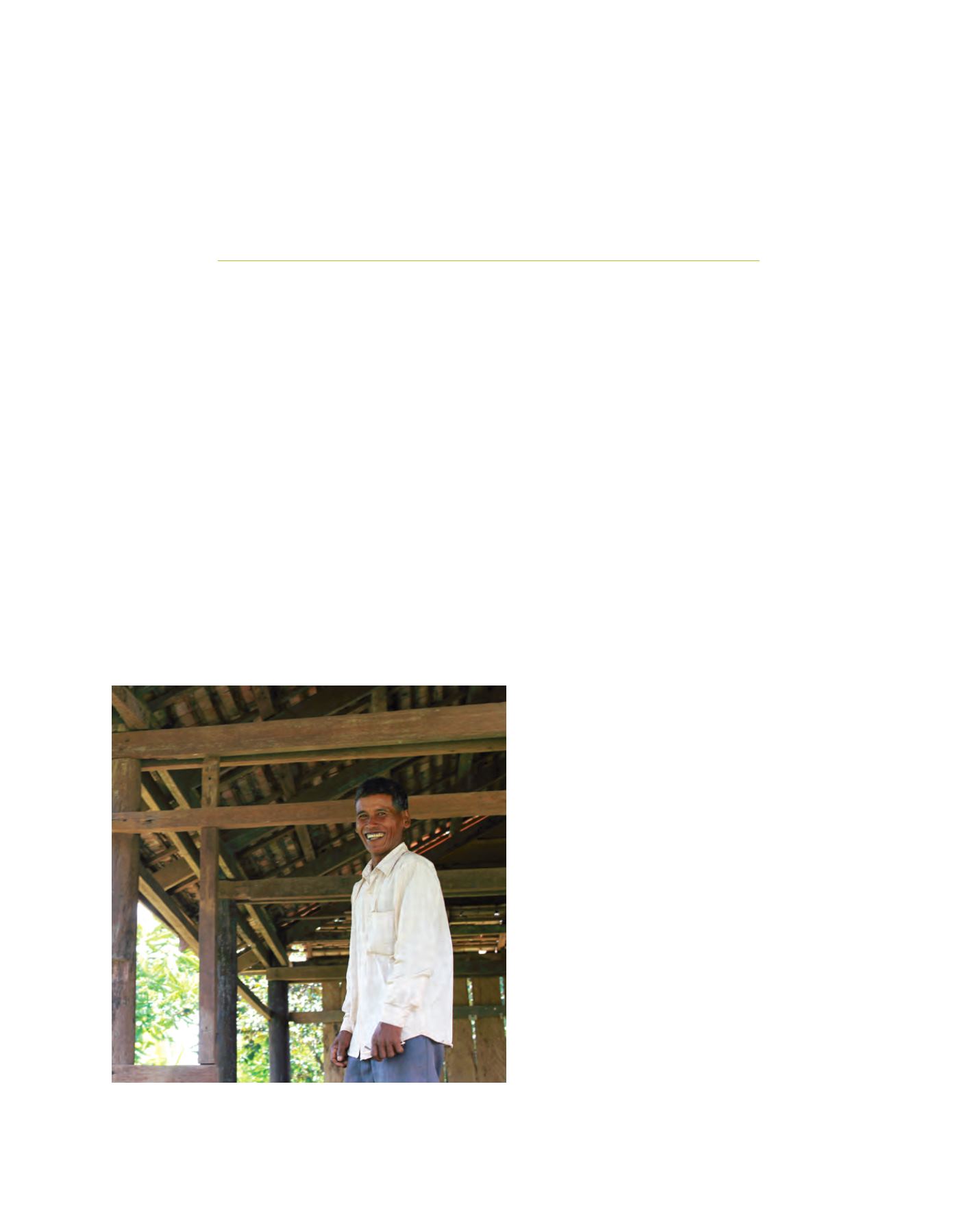

Sorn Yam, Chairperson of the Community Forest Management Committee, worked

for three years through six stages of approval to get legal recognition “otherwise the

forest will be lost”

Image: Alison Rohrs, RECOFTC