[

] 220

the local people also report illegal activities to me which is very

helpful since I have a large area to patrol.”

Over the course of four years, the Capacity-building for Sustainable

Forest and Land Management Project delivered a massive grass-

roots training programme through 70 field-level training sessions

on community forestry. Beginning with 33 nationals who became

community forestry trainers, a further 1,416 individuals were trained

to understand the process and benefits of the community forests

programme, the most important being secure rights over forest lands.

Once the long procedure for legal recognition was over, the next

step was learning to manage the forest lands. Through other livelihood

support programmes, local administration officials and communities

were also taught to develop sustainable forest management plans.

Rebuilding livelihoods

For Ms Chea Tun, a mother of seven, life in Kbal O KraNhak has

changed from an uncertain struggle for survival to an assured harvest

of rice and soya beans in addition to the cassava that she grows

upland. “I know the agreement was signed, and I feel more secure

that I can use forest materials, like firewood, mushrooms, vines to

make fences, and resin,” she says. “Some members of the community

collect resin. If I want a bit, they give it to me for free. We mix it with

bark and use it as fuel to light the stove.”

Having realized the economic value of their forest land once more,

the community is determined to protect it. “We used to talk about

how to stop locals and outsiders from cutting down trees,” says

Chea Thun, “but there was nothing we could do to stop them. We

have more power now that we signed the community forest agree-

ment. This year, an outsider was cutting down trees illegally. We

tracked him down and confiscated his materials. Then we reported

it to the Forestry Administration.”

In Kampong Thom, as in other areas, the programme is also

encouraging women to take an active part in the drawing up of

Forest Management Plans. The Manage our Forests project is active

in Kampong Thom and Kratié provinces and is helping 21 villages

create and implement management plans for 20 community forests.

Community forestry training is a key function of these projects.

During 2009-2010, the three projects hosted 54 field training events

and involved 1,339 participants from the Forestry Administration,

Government agencies, NGOs and local community forestry groups.

Ms. Sao Saveun, for instance, took over her husband’s elected seat on

the committee and is actively involved in management, inventory,

and patrolling of forest areas.

Mua Amkon, a community forest member from Boengkok village

in Kampong Chhnang sums up their common narrative: “When I

was young, this whole village was forest land. Only a few families

lived here. We used the forest for building a few small houses, for

cow sheds and for collecting firewood. During the Pol Pot regime,

the forest was cleared to make a coconut plantation. Starting from

around 1980, more and more people moved in and needed farm-

land, so they cleared the forest, and it disappeared. I really regretted

seeing the forest disappear. We used to have a lot of trees, and then,

almost nothing was left. But now, we can protect the forest. We are

lucky to have the opportunity.”

In 2010 Beongkok village joined the ranks of legally recognized

community forests in Cambodia. In that same year, the National

Forest Policy (NFP) for 2010-2030 was approved, paving the way

for legal and policy reforms in the forestry sector. In recognition

of forests’ essential contribution to national development, the

NFP emphasizes the importance of good governance

and promotes community forestry specifically under

Programme 4 of its six-point programme. Indeed the

strategic direction for Objective 8 states community

forests have ‘demonstrated considerable potential to

protect forests and support rural livelihoods. Recently

community forestry has expanded from low value

forest to also include more valuable forest’.

RECFOTC continues to engage not only in formali-

sation of community forests but also in community

forest networking, management plans and enhance-

ment of rural livelihoods. Through a ‘programmatic

and partnership’ approach, it hopes to contrib-

ute significantly to the achievement of the goals

and targets of the Community Forestry Program of

National Forest Program (2010-2029) endorsed by

the Royal Government of Cambodia in October 2010.

Together with the Spanish Agency for International

Cooperation and Development and the European

Union, RECOFTC has also expanded its coverage to

some 200 community forests in ten of 24 provinces in

the country. And yes, that’s more good news for the

villagers of Kampong Thom.

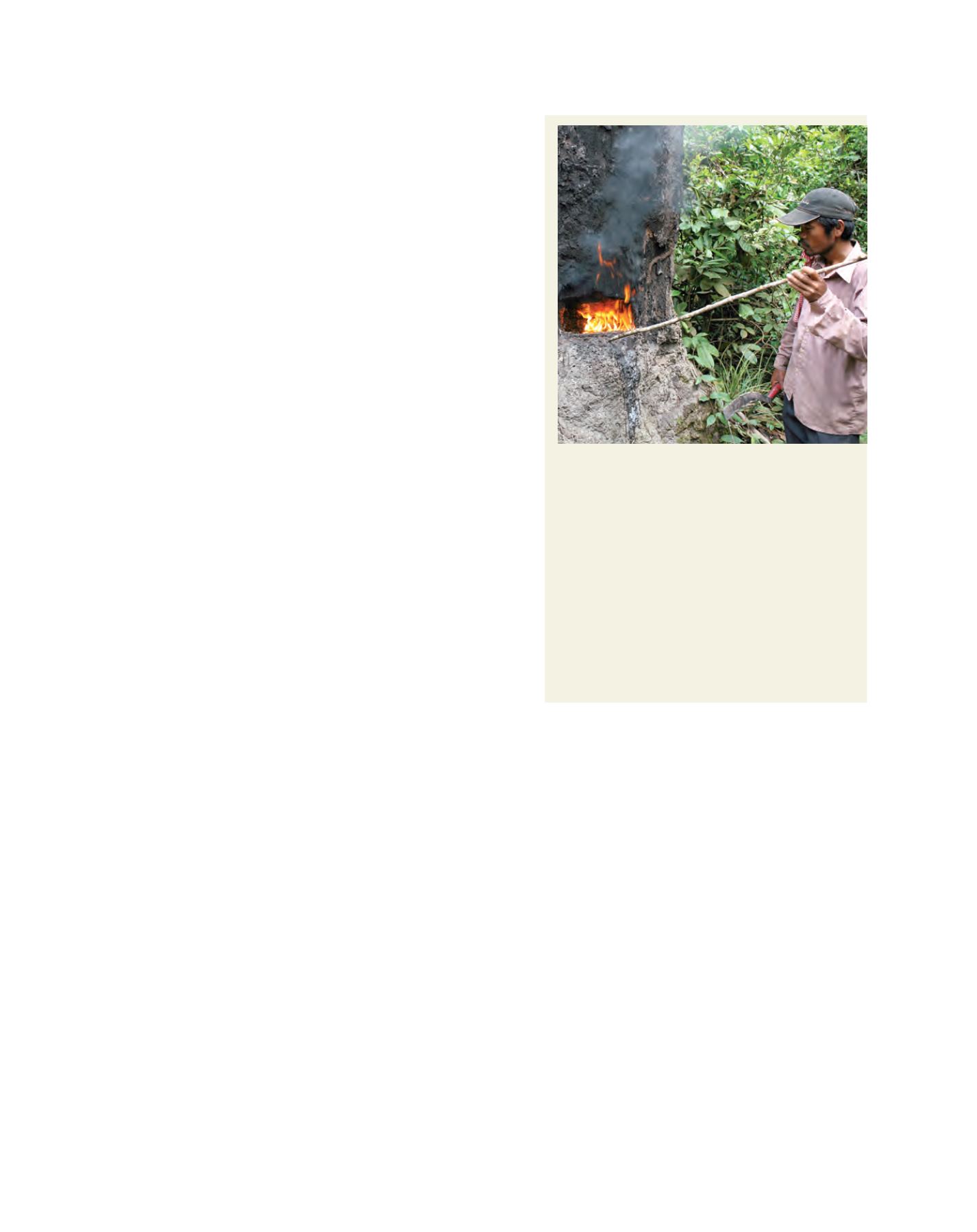

Mr Teav Pot collects resin from a

dipterocarp tree

. He can

sell the resin for 30 cents a kilo or trade it for rice. Resin is

a primary non-timber forest product for the community, used

for sealing furniture, making soap, and fuelling lamps and

stoves. Although the process looks harmful to the tree, resin

can be collected sustainably. A small cut is normally made

in the tree, and heat from a small fire causes the resin to

flow. Studies in southern Mondulkiri province reported that

86 per cent of families owned resin trees, with an average

of 77 trees per family. The income from the sale of resin

averaged US$3.6 per tree per year (with a mean annual

income per family ranging from US$299-377 across four

villages). The total annual income from resin sales across

the four villages was US$61,000.

6

Of the 11,000-18,000

tons of resin collected in Cambodia each year, approximately

3,000-4,000 tons is sold domestically and the remainder is

exported to Viet Nam, Thailand and Lao PDR.

Image and interview: Alison Rohrs, RECOFTC