[

] 88

example, to contribute to the forest debate from their own, forest-

related perspectives.

11

Two other kinds of governance arrangements deserve attention.

First, several efforts to enhance forests and forestry practices have

emerged at the regional level in response to the ‘treaty congestion’ in

the UN system. An assessment report found 11 legally binding regional

agreements and at least 13 non-legally binding processes and arrange-

ments.

12

In terms of effectiveness, the key factor was not the kind of

instrument used, since many have a mix of legal and other instru-

ments. The more successful regional initiatives differ decisively from

the ineffective ones because of their links to regional polity-building

projects. Forest governance in these frameworks serves wider political

interests, making voluntary coordination more effective by embed-

ding it within regional governance structures. Both ASEAN and the

EU show that such intergovernmental and supranational governance

structures provide powerful support for forest governance initiatives.

Second, section III of Agenda 21 states that ‘one of the fundamen-

tal prerequisites for the achievement of sustainable development is

broad public participation in decision-making’ and that ‘the commit-

ment and genuine involvement of all social groups’ is ‘critical to the

effective implementation of the objectives, policies and mechanisms

agreed to by governments in all programme areas of Agenda 21.’

Since Rio, it has become very clear that the problems and issues

related to sustainable development, including forest issues, cannot

be addressed solely by governments through intergovernmental

agreements. Non-governmental actors, both for-profit and not-for-

profit, have a vital role to play other than as sources of advice and

legitimation for state-led processes. The growing significance of

policy coordination at a global level by actors without formal author-

ity to do so is also captured by the term ‘governance’. Non-state

governance is conducted by international organizations acting as

agents for states, but also by ‘global social movements, NGOs, tran-

snational scientific networks, business organizations, multinational

corporations and other forms of private authority’.

13

Significantly,

such new forms of coordination are very often found in response

to the challenges arising from the complexities of environmental

protection and sustainable development

14

and have been observed

in forestry-related contexts at national and subnational levels.

In forest governance, most of the attention has been directed towards

the various competing schemes for certifying forest products as deriv-

ing from sustainably managed sources. However, efforts at

broader inclusion in intergovernmental processes, public

private partnerships and corporate-NGO partnerships

have become common in the forests arena. Inclusion has

generated funding and capacity for policy implementation

on the ground and supported moves towards decentral-

ized implementation of SFM. For example, the Congo

Basin Forest Partnership (CBFP) and the Asia Forest

Partnership were both launched at the World Summit

on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002,

which gave special attention to the roles of public-private

partnerships in promoting sustainable development. The

CBFP, currently facilitated by Germany, has generated

significant additional funding to support forest conserva-

tion and sustainable forest-based livelihoods in the region.

In keeping with the connection between governance

and devolution, a number of regional and interna-

tional initiatives have also emerged that are focused

on grass-roots and community approaches to engag-

ing local people in addressing forest issues. These

include, among many others, Forest Connect, Growing

Forest Partnerships, Rights and Resources Initiative,

Responsible Asia Forestry and Trade and The Forests

Dialogue (in partnership with UNFF). Existing

grass-roots initiatives are also strengthening their inter-

national engagement, especially in the REDD+ context,

including the Asia-Pacific Center for People and

Forests, Coordinating Association of Indigenous and

Community Agroforestry in Central America, Global

Alliance of Community Forestry and International

Family Forestry Alliance, to name only a few.

As a result of these developments, an increasingly

distinct and comprehensive set of international goals

and priorities has emerged to steer forest use and

conservation, accompanied by institutions, policies and

mechanisms. The result is a complex and fragmented

web of forest governance at all levels, the constantly

evolving outcome of many different initiatives rather

than the product of an overall design.

This outcome is not necessarily sub-optimal. A single,

overarching governance instrument would require a

level of agreement on the nature and relative priority of

forest problems that has been absent from international

forest negotiations and still shows few signs of emerging.

A recent assessment of international forest governance

demonstrated that, looked at in terms of the full spec-

trum of policy problems raised by forests, the coverage

of the various agreements and initiatives considered

together as a ‘global forest governance architecture’ is

rather comprehensive.

15

The problem, the assessment

concluded, is ultimately one of metagovernance: how

to coordinate coordination itself so that the key goals

of improving forest conditions and livelihoods are not

lost amidst a welter of competing objectives coming

from the various forest-related governance initiatives

that now dominate forest governance at most levels.

This problem of coordinating governance arrangements

themselves has often been recognized but the challenge

of forest metagovernance has not yet been met.

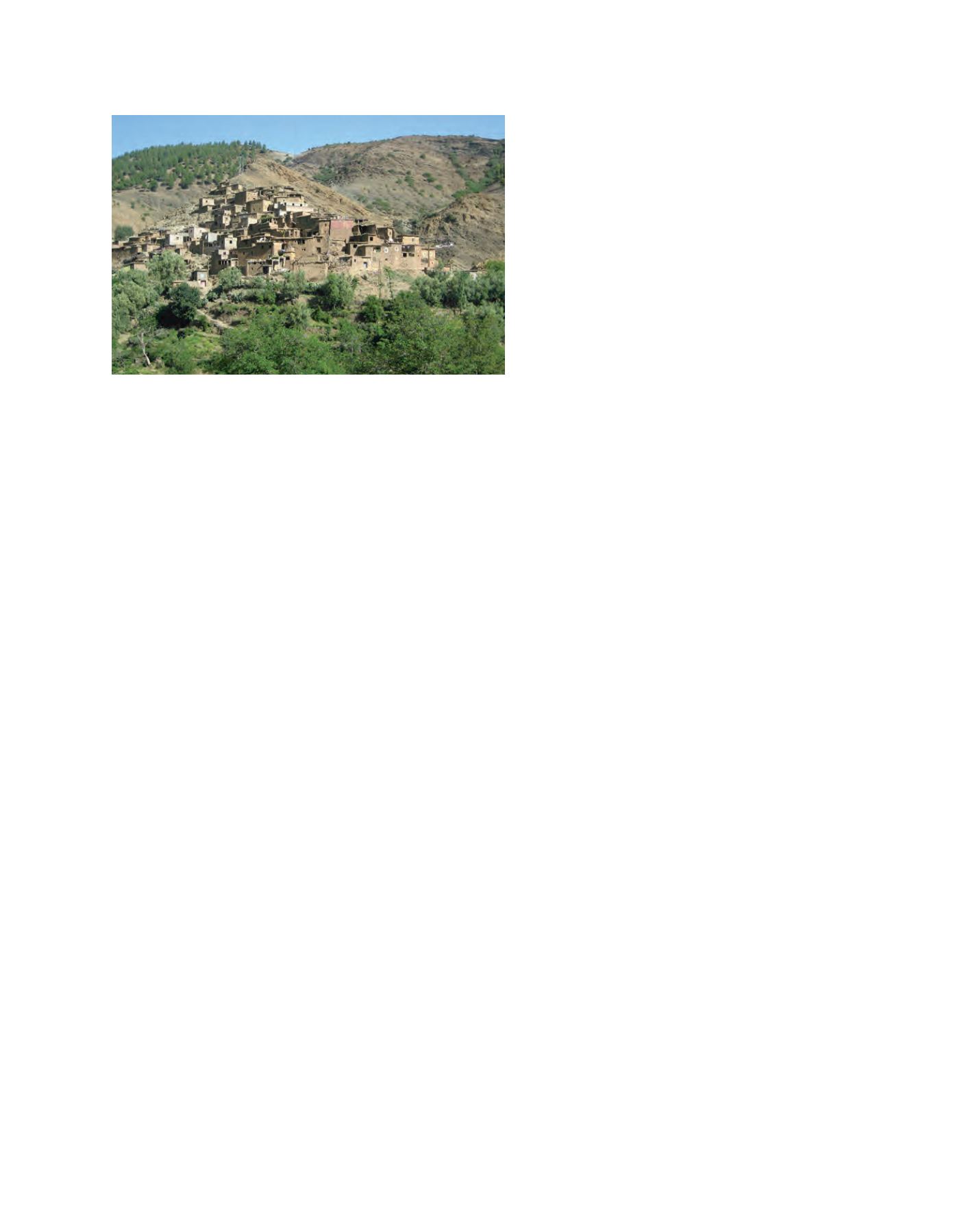

There have been several initiatives based on grass-roots and community approaches

to forest issues

Image: IUFRO