[

] 165

F

inancing

C

ooperation

market-based services. This model can bring together various (and

often unconventional) actors to affect sustainable change.

Case study: Bangladesh

Bangladesh has one of the highest population densities in the world,

with a population of approximately 160 million people and a land mass

smaller than the nation of Greece. According to the Joint Monitoring

Programme in 2010, more than 28 million people in Bangladesh lack

access to an improved water source and 66 million lack access to proper

sanitation. This problem is especially acute in the capital city Dhaka,

which is widely described as a sprawling megacity by aid institutions.

With a population of more than 12 million and an annual population

growth rate of more than 5 per cent, Dhaka has experienced enormous

difficulties in meeting water and sanitation needs. Approximately 85

per cent of urban slum residents in Dhaka do not have access to safe

water, and an estimated 40 per cent do not have a toilet.

Due to rapid urbanization in Dhaka and other major cities, the

Government of Bangladesh has emphasized access to safe drink-

ing water and sanitation facilities in urban areas. Nearly a third of

Dhaka’s population lives in urban slums and lacks legal access to

safe water connections. According to local laws, community resi-

dents need city approval before they can connect to city water pipes,

and this is only given to residents who can provide proof of land

ownership. While government agencies wanted to increase access in

slums, legal restrictions left the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage

Authority (DWASA) without the ability to carry out its mandate.

One of

Water.org’s partners in Bangladesh – Dushtha Shasthya

Kendra (DSK) a local non-governmental organization (NGO) in Dhaka

– stepped in to help fill this critical gap. DSK’s founder, Dr Dibalok

Singha, saw that slum residents were forced to pay high prices for unsafe

water supplied by slumlords, or they bought expensive bottled water

from the ‘water mafia’ in Dhaka, often at 15 times the rate that DWASA

charged legal water customers. Dr Singha met with DWASA’s leader-

ship to figure out how they could cooperate and reach those without

safe water access. DSK had a simple solution to a complex problem:

empower the poor to become water and sanitation

customers, and rely on their desire to improve their lives.

Dr Singha convinced DWASA that slum residents would

repay water and sanitation loans if given the opportunity.

In the end, he successfully lobbied the city to provide a

water licence to his NGO on behalf of participating slum

communities. Philanthropic grant funding enabled staff to

build water and sanitation infrastructure, such as house-

hold water connections and toilets.

In 2004, after witnessing the powerful relationship

between DSK and DWASA,

Water.orgrealized there

was an opportunity for its new WaterCredit initia-

tive. After reaching an agreement,

Water.orgprovided

a philanthropic grant or initial ‘smart subsidies’ to

DSK, designed to attract and leverage additional social,

commercial and civic capital and to cover fixed costs

for starting up the new loan development process and

enhancements to its loan tracking system. This enabled

DSK to pilot and roll out water and sanitation loans

in target slum communities. The staff also learned that

additional capital could grow and further scale the loan

programmes, thus creating a natural ‘multiplier effect’.

By taking this crucial first step and believing in the

intrinsic power of the poor,

Water.org, Dr Singha and

DSK were able to reach more underserved communities

with critical services, and increase the focus on the level

and nature of demand.

In this particular WaterCredit programme, DSK

provides loans for both community and household-

level water and sanitation improvements. To initiate

the process, DSK’s staff works with the slum commu-

nity to help form gender-balanced water and sanitation

committees. Each committee then pays to install water

pumps or toilets, and the costs of operation and main-

tenance. The committees also collect and pay the water

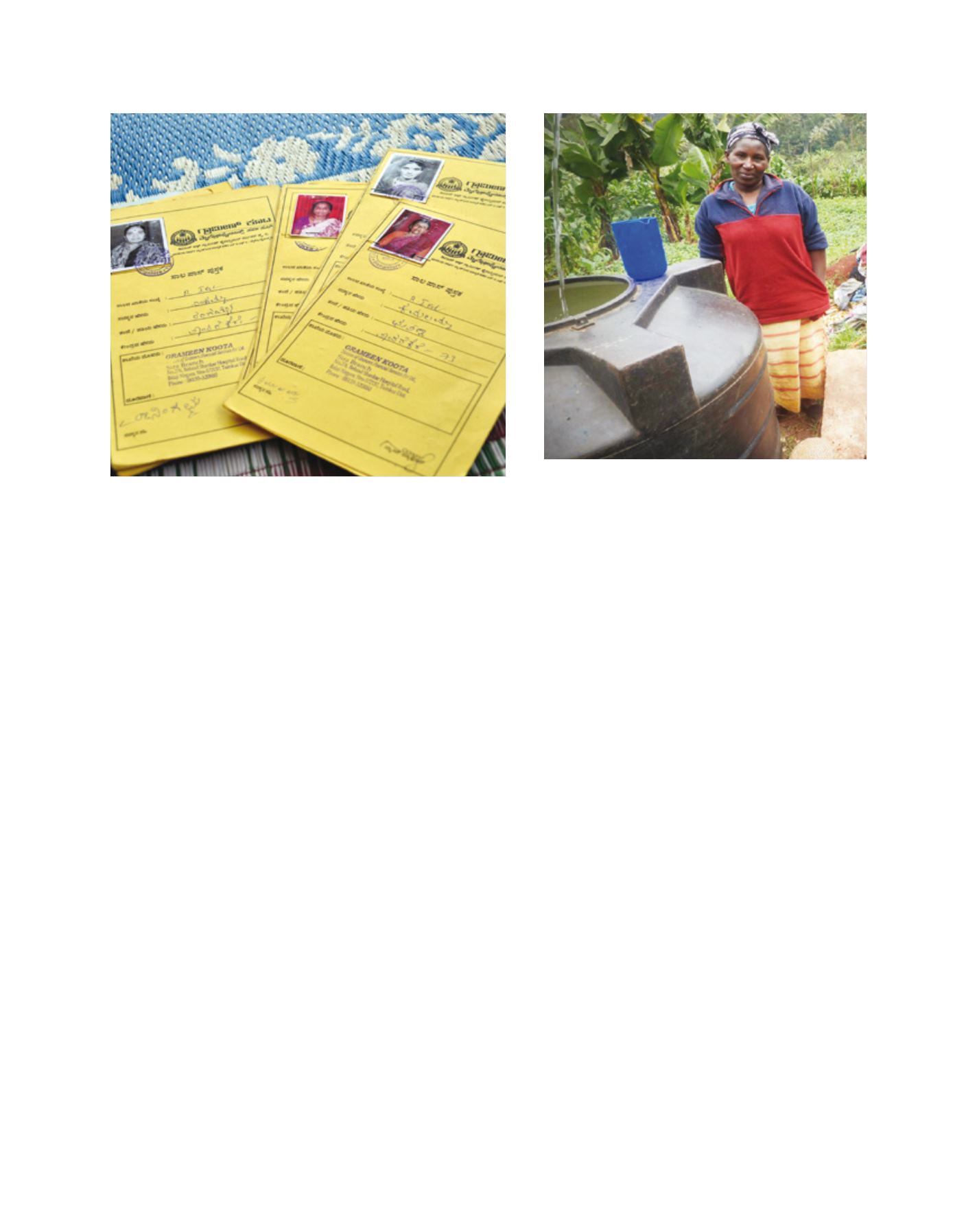

Borrowers are given loan cards to track their loan balance and repayments

Rose Nungari uses her rehabilitated well and storage tank, obtained

with a WaterCredit loan, for household use and to irrigate a garden

Image: Water.org

Image: Water.org