[

] 220

W

ater

C

ooperation

, S

ustainability

and

P

overty

E

radication

edge-based approach to bridging yield gaps with a mission-mode

initiative, forming a consortium and a network for stakeholders to

share their knowledge about the weather, soil health and improved

management practices across all 30 districts in the state. The

overwhelming impact has strengthened the partnership between

ICRISAT and the GoK, and eight major Consultative Group on

International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) centres have been

invited, along with AVRDC (the World Vegetable Center), to work

towards improving rural livelihood systems in four benchmark

districts representing different agroecological zones in the state.

Up-scaling the benefits of integrated watershed management

necessitates an articulated strategy based on the main pillar of

capacity building of all stakeholders, including farmers, research-

ers, development workers, policymakers and development investors.

New scientific tools such as remote sensing, geographical informa-

tion systems and crop simulation modelling for the analysis of

long-term potential productivity, need to be used as the planning

tools. These tools provide the capabilities for extrapolating and

implementing the technologies to other larger watersheds.

The ICRISAT consortium focused on training farmers, personnel

from development agencies and NGOs through demonstrations of

different technologies on benchmark watersheds, and acts as a mentor

for technology backstopping. The farmers’ community, through

village institutions, took responsibility for all activities of implemen-

tation and monitoring. Government and non-governmental agencies

catalyzed the process. The important aspect while evaluating and

scaling-out this approach is that the relevant government line depart-

ments must be included in the consortium along with other partners.

The role of policymakers and development investors is critical, and

sensitization of these stakeholders played a major role in

scaling-out the benefits in Asia.

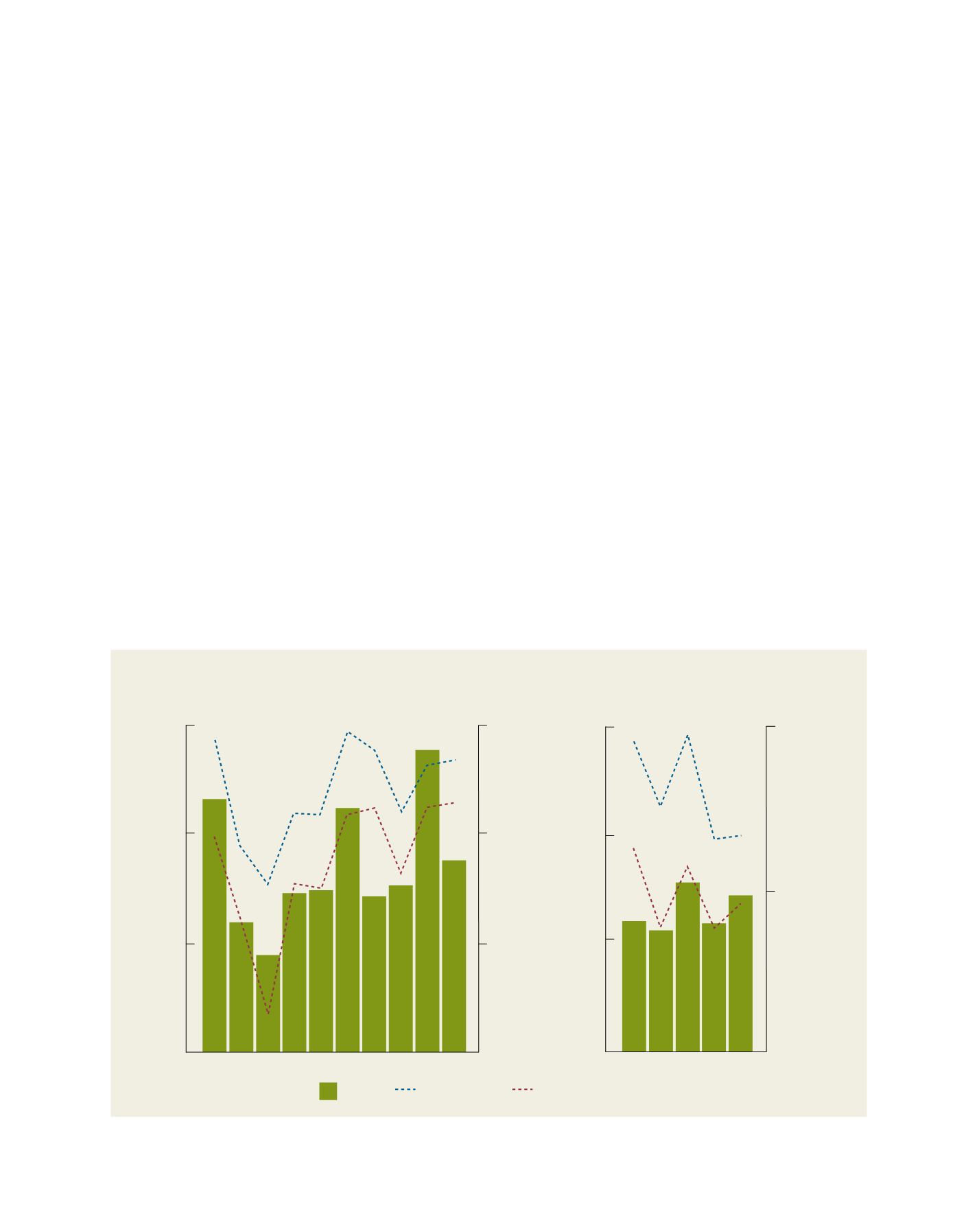

Impacts and outcomes

An innovative integrated watershed management model

developed by ICRISAT and its partners produced a wide

range of impacts. Close monitoring of groundwater

resources in different watersheds in India confirmed

that water harvesting structures sustained good ground-

water yield even after the rainy season. For instance, in

the Lalatora watershed in Madhya Pradesh, the ground-

water level in the treated area registered an average

rise of 7.3 metres; at Bundi watershed in Rajasthan a

5.7 metre increase was observed, and at the Adarsha

watershed, Kothapally in Andhra Pradesh, a 4.2 metre

rise in groundwater was recorded. In Adarsha water-

shed, a study showed that nearly 60 per cent of the

run-off water was harvested through agricultural

water management interventions which also recharged

shallow aquifers. Water harvesting structures (WHS)

resulted in a total 6 metre rise in the water table during

the monsoon. At the field scale, WHS recharged open

wells at a 200 to 400 metre spatial scale.

11

The various

WHS resulted in an average contribution of seasonal

rainfall to groundwater during the normal rainfall year

of 27-34 per cent in Rajasamadhiyala and Shekta water-

sheds.

12

In the Adarsha watershed, due to additional

groundwater recharge, a total of 200 ha were irrigated

in the kharif (autumn) season and 100 ha in the rabi

Rainfall

Near check dam

Adrasha watershed, Andhra Pradesh

Bundi watershed, Rajasthan

18

0

12

6

Waterlevel in well (m)

Rainfall (mm)

Rainfall (mm)

0

1500

500

1000

Away from check dam

2000

2003

2006

2009

18

12

6

0

Waterlevel in well (m)

0

500

1000

2002 2004 2006

Mean annual groundwater levels in wells as influenced by the water harvesting structures at Kothapally and Bundi watersheds

Source: Wani et al., 2010