[

] 226

W

ater

C

ooperation

, S

ustainability

and

P

overty

E

radication

management model, board-like structures with tripartite compo-

sition – public authorities, water users and civil society – were

structured not only as a platform for public debate but, above all, as

permanent water forums endowed with deliberative powers to steer

the implementation of planning and economic instruments.

Over the past 25 years, almost 200 river basin committees have been

established throughout the country covering an area of more than 2.1

million km

2

, almost a quarter of Brazil’s territory. During that same

period, water councils with a composition similar to that of river basin

committees have been established in all states and at the federal level.

These forums function as ‘water parliaments’ and today they consti-

tute the main political arena for integrating water-related policy sectors.

An estimated 9,800 people are currently involved with the political

activities carried out in water councils and river basin committees, of

whom more than 3,000 are representatives of organizations in civil

society including non-government organizations, professional associa-

tions and centres of higher education and research.

Despite the operational difficulties of running a decentralized

system in such a vast territory, including high transaction costs

and acute asymmetries of knowledge and organization among

stakeholders, the benefits of transition from centralized, state-led

policymaking to the current model are undeniable. For the first

time non-state actors, particularly small community organizations,

have had an opportunity to influence high-level political processes.

They can have their say in matters of public and private investments

in water infrastructure, the definition of environmental standards

for protection of surface and groundwater, and allocation of water

resources among different sectors of the economy.

Besides providing institutional channels for citizen participation

in the decision-making process, these water councils and river basin

committees also created an enabling environment for collaborative

water governance. New forms of intersectoral and inter-institutional

partnerships have been developed around distinct forms of water

cooperation: public-public, private-private and public-private.

One example is the River Basin Clean-Up Program (PRODES)

that offers output-based aid (OBA) for sanitation services, binding

public funding of sanitary infrastructure with decisions on water

pollution control made collectively by members of these water

forums. Another example is the Water Producer Program which

offers technical and financial support for payment for environmental

services (PES) initiatives, many of them carried out at the watershed

level. The existence of an operative river basin committee is a key

factor for success in PES schemes, as they contribute to bringing

potential buyers and sellers together and facilitate the crafting of

multi-stakeholder agreements. Once the institutional arrangements

are in place, it is possible to overcome often-observed conflicts that

usually stem from the use of coercive instruments under command-

and-control strategies.

Integrated water management

Both the division of inland waters between federal and state

jurisdictions and the establishment of a national system of water

management as set out in the Federal Constitution of 1988 have

posed a great challenge for water governance in Brazil. The challenge

is intensified when one considers that, according to the National

Water Act of 1997, watersheds are the basic territorial units for

implementing water policies.

It demands Herculean efforts to establish permanent and effective

means for integrated water resources management (IWRM) nation-

PRODES

Objective:

Improve water quality in urban areas by

reducing water pollution from discharge of untreated

sewage and incentivizing implementation of water

policy instruments

Strategy:

OBA

Water sectors/users involved:

Sanitation services

(wastewater treatment)

PRODES offers OBA-type subsidies to reimburse up to

100 per cent of capital costs for the construction of new

wastewater treatment plants or improvement of existing

facilities. Once OBA contracts are signed, the funds

are transferred from the National Treasury to specific

escrow accounts. Service providers have then two years

to finish construction and start operation. From this

moment, a three-year certification process is initiated,

with evaluation of operational performance every three

months. Disbursement of federal grants is conditional

on the achievement of performance goals in wastewater

treatment facilities, with incumbent operators bearing all

the risk of non-performance.

From its launch in 2001, PRODES aimed at integrating

sanitation and water management policies, for which

a set of measures were adopted. For example, river

basin committees were tasked with approving proposals

for investment and operational performance goals

presented by sanitation services operating in their

areas. Proposals were selected on the basis of a more

holistic view over water quality problems, considering

their adequacy with the overall strategy set by river basin

committees. Criteria for selecting proposals were linked

to water policy goals, favouring those located in regions

that had advanced further in the implementation of

water policy instruments.

Key results

From 2001 to 2012, PRODES provided approximately

US$129 million to sanitation services that fulfilled

their contractual obligations in terms of water pollution

control in Brazil. In all, 58 projects were supported in

areas with critical conditions of water quality. These

facilities have a total operational capacity to remove

106,000 tons of organic pollutant load per day, serving

a population of approximately 5.3 million.

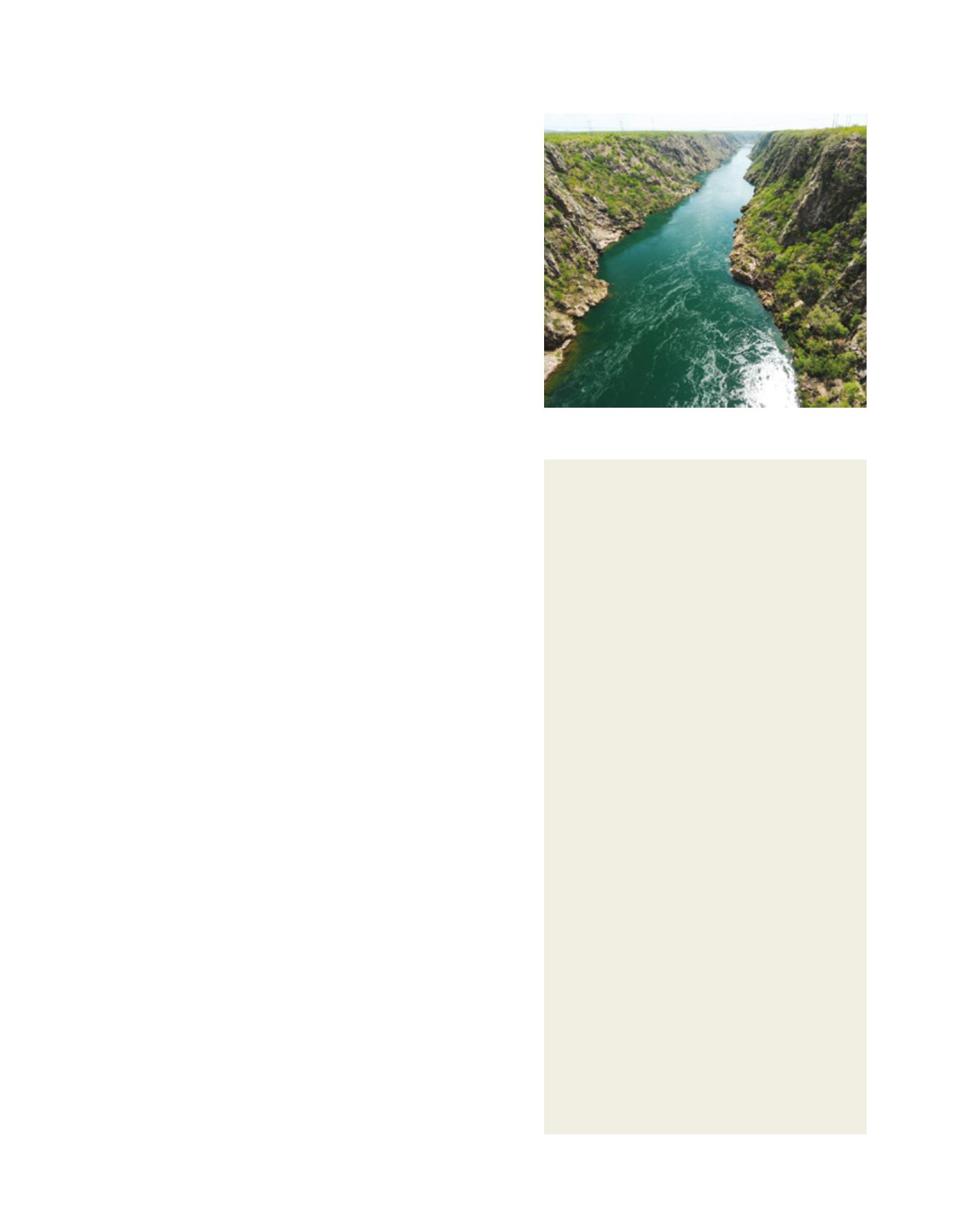

Image: Zig Koch courtesy of the National Water Agency

São Francisco River near the Paulo Afonso Hydropower Plant