[

] 228

W

ater

C

ooperation

, S

ustainability

and

P

overty

E

radication

level involving all stakeholders represented in state water councils.

Members of state councils will be responsible for establishing policy

goals for their own state systems based on the major water chal-

lenges identified in their regions. In addition, state water councils

will be in charge of overseeing compliance with these goals on an

annual basis, a condition that will determine whether or not state

public authorities receive federal grants.

This is part of a new goal-oriented initiative called Progestão

(Pro-management). In this case, however, the ultimate goal is not

to improve water quality by intervening on water-related policies

but to induce continuing advancements in water policy through

a permanent cooperation effort between the federal government

and the states.

Only states that become a party to the National Pact will be eligi-

ble to receive funds from Progestão. Individual contracts will be

signed with each partner state, in which agreed water policy goals

will be translated into contractual goals and obligations for a five-

year period. Funds will be made available to state public authorities

at the beginning of each fiscal year, according to the policy goals

they have achieved the previous year.

As such, non-state actors will play a greater role in Brazil’s

water policy. Water cooperation among federal and state public

authorities will no longer be restricted to isolated, dissociated and

time-limited initiatives.

Challenges ahead

Keeping to the old course of state-led and centralized water

policymaking would certainly be an easier political option in a

newly-borne democratic regime. From the beginning, it was evident

that involving citizens in water-related decision-making processes

and coordinating state action in a three-tier system of government

would be a challenging task. Nonetheless, that was the option taken

in 1988 by the framers of the new Brazilian Constitution and by

lawmakers that, a few years later, enacted the first state water laws

and the National Water Act in 1997.

It is still too early to say whether water managers in Brazil will

cope with the challenge of implementing the envisioned water

governance model. But it is certain that their chances of success

depend on their cooperation with each other. Water cooperation in

Brazil will be crucial to securing the democratic values embedded

in its legal framework.

Important steps have been taken in the right direction. Periodic

meetings and face-to-face interactions in councils and committees

have provided some of the cement that made state and non-state

actors cooperate with each other – and cooperation among them

improved significantly over time. The continuing exercise of politi-

cal judgement, of questioning each other’s view on matters of water

management, of agreeing to disagree, of trying to build consensus

and majorities – all this has contributed to reaching a new level of

water governance in Brazil.

But an even bigger challenge lies ahead: to promote coopera-

tion on water throughout the federal system and across different

branches of the public sector. Goal-oriented strategies such as OBA

and PES have been used to integrate water-related policies with posi-

tive results so far. Now another results-driven programme will be

tested as a mechanism for integrating federal and state actions. Will

it work? It is not possible to say at this moment, but considering that

IWRM is the missing part of Brazil’s democratic governance model,

it is worth trying.

Water Producer Program

Objective:

Improve water quality by tackling nonpoint

sources of pollution in rural areas

Strategy:

PES

Water sectors/users involved:

Irrigated agriculture and

water supply systems

The Water Producer Program was launched by the

National Water Agency of Brazil in 2006 with three main

objectives: conservation of riparian forests, improvement

of soil management in rural areas and recovery of

degraded areas in watersheds. It aims to substitute

costly instruments of control based on coercive and

regulatory actions with the use of less hands-on public

governance tactics that rely on economic instruments

and inter-organization networks. Payment is taken for

watershed services as a strategy to overcome common

barriers to resolving disputes, bringing stakeholders

together as partners in joint projects to prevent

environmental degradation.

The first steps of the programme involve a general

assessment of major environmental problems,

investment needs and, most importantly, potential

buyers and sellers. This initial assessment is a key

element in defining targets, service baselines and overall

procedures for monitoring and assessing compliance.

Negotiations then take place between upstream service

providers (landowners) and downstream water users

(water supply systems) and, if agreement is reached,

payment schemes are set up for recovering degraded

areas or preventing environmental damage.

Key results

From 2006 to 2012, the programme supported 20

PES initiatives in 13 different states. These include

the Water Conservationist Project, the first water PES

scheme established in Brazil, which is known for its

strong engagement of municipal government and local

stakeholders. In all, these initiatives cover an area

of 306,000 hectares, including regions that supply

water to seven state capital cities (São Paulo, Rio de

Janeiro, Brasilia, Rio Branco, Palmas, Campo Grande

and Goiania). Around 2,000 landowners are presently

receiving payments for watershed services.

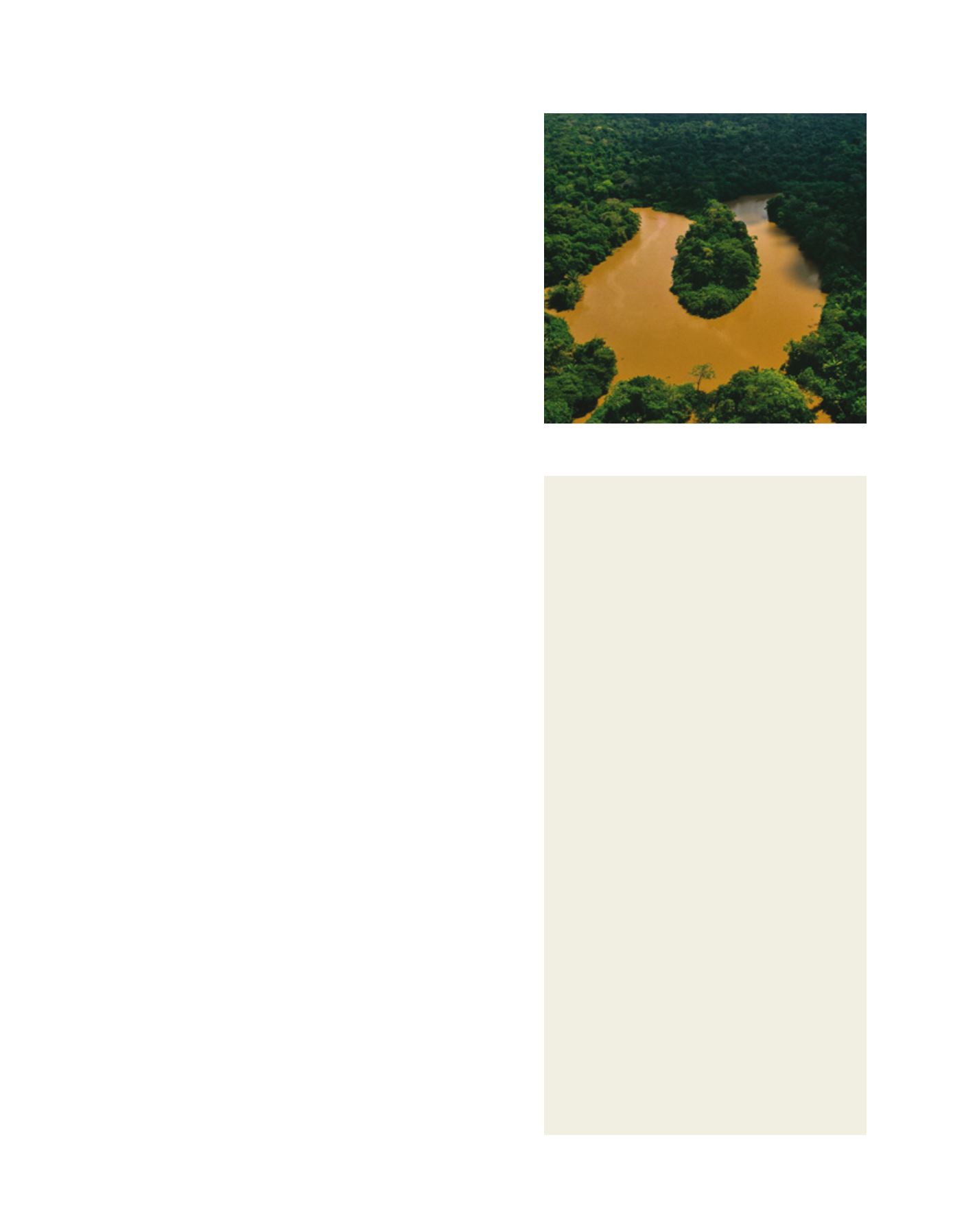

Image: Rui Faquini courtesy of the National Water Agency

Mexiana Island in the Amazon Basin