[

] 276

E

conomic

D

evelopment

and

W

ater

city must provide green infrastructure more generally,

not just a sustainable water catchment for itself – the

imperative upheld by the first pillar.

Landscapes are the product of both natural and

human forces, interacting in regional ecosystems

and beyond. Public spaces are essential to public

amenity – or putting it differently, to the material

conditions that enable human flourishing. However,

urban landscapes must be functional beyond provid-

ing amenity. Our conception of the value inherent in

open space needs to be enlarged, by consideration of

the ecological functioning of urban landscapes. This

expanded view encompasses great diversity: sustain-

able water management, microclimate influences,

facilitation of carbon sinks, use of ‘low-mileage’ food

production, environments for wildlife and more.

Excluding the urban environment from this interwo-

ven fabric is yet another reductive, binary-thinking

notion that has outstayed its welcome. Three broad

themes characterize the ecological design objectives

for urban landscapes: nature conservation (building

and conserving biodiversity, in terrestrial and aquatic

environments of the city); urban-rural interface

management (protecting and rehabilitating high-

conservation areas regardless of where they are found,

and mitigating the environmental impacts of urbaniza-

tion); and urban ecology (urban design incorporating

to reduce their dependency on externally sourced water, includ-

ing desalination of seawater, by accessing locally derived water

in a portfolio of water sources. A serious departure from nine-

teenth and twentieth century thinking? Yes. The old plans and

precepts are unworkable, as even the current state of cities makes

clear. Traditional mechanisms of governance yield fragmented

infrastructure and compartmentalized service provision. These

reductive ‘either/or’ approaches have had their day and new, holis-

tic, integrated solutions are called for. We need more sophisticated

perceptions of system boundaries, whereby a city may be seen as

both a generator and a consumer of essential resources. Embracing

the concept of diverse water supplies and mixed infrastructures

will give cities enormous flexibility, freeing them to access a wealth

of sources at minimal cost. Each of the alternative water sources

will have its own level of reliability and its own environmental

cost-and-risk profile. In a future water sensitive city, each source

can be optimized through diversified and parallel infrastructures

– for water harvesting, water treatment and new ways of storage

and delivery. Depending on a city’s particular conformation and

needs, the mix might include both centralized and decentralized

elements – from a simple rainwater tank for non-potable use to

large-scale schemes for redirecting or reusing water.

The second pillar supporting water sensitive cities, cities provid-

ing ecosystem services, has a place close to the first. Like it, this

pillar stands against traditional ways that have outworn their useful-

ness; but now the principle is broader. We may consider it under the

heading ‘water sensitive urban design’ (WSUD). The water sensitive

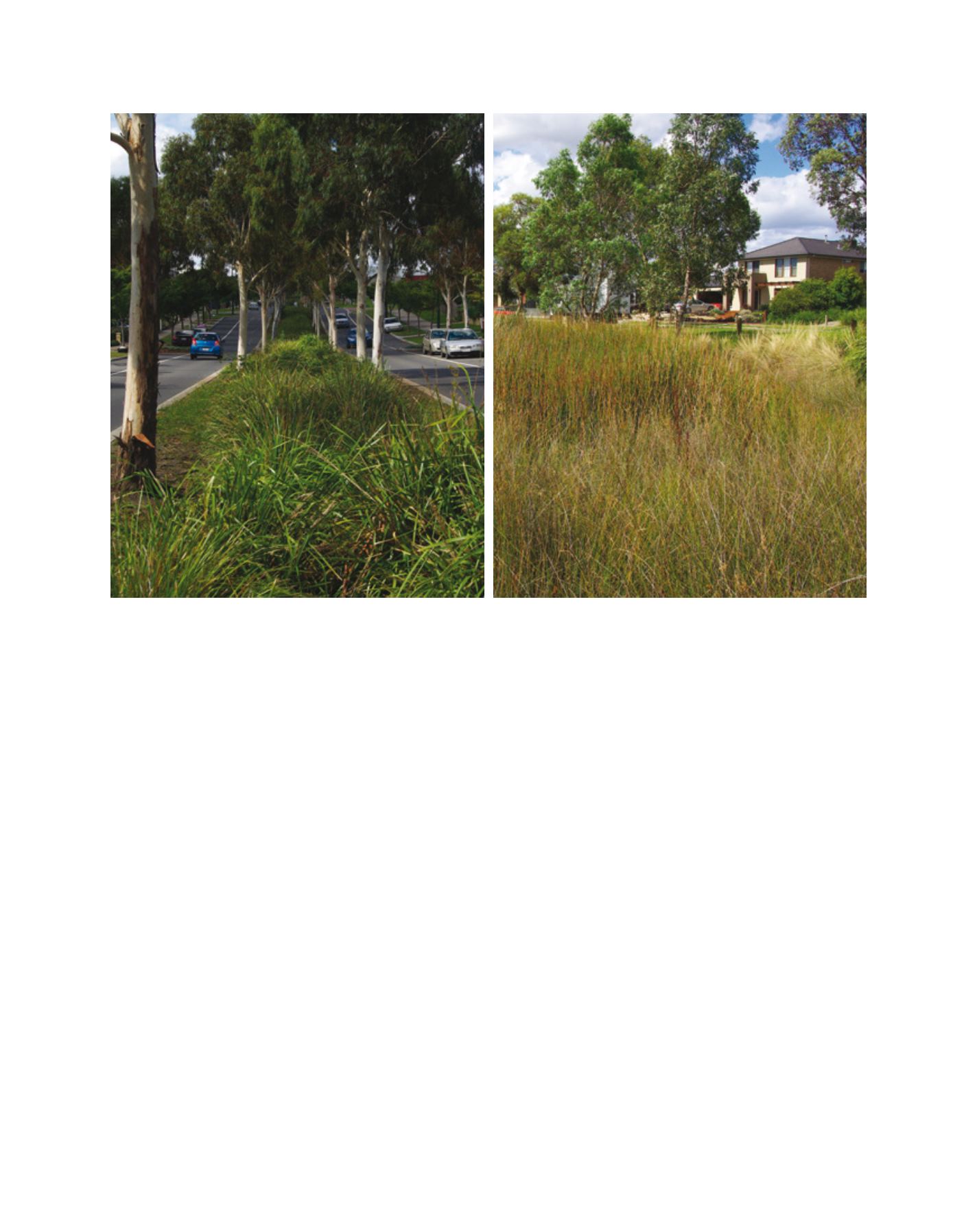

Green corridors and constructed wetlands are multifunctional green infrastructure, providing ecosystem services including water quality improvement,

micro-climate enhancement, flood conveyance and increasing biodiversity

Image: Tony H. F. Wong