[

] 277

E

conomic

D

evelopment

and

W

ater

bio-mimicry, towards green infrastructure that organically inte-

grates anthropogenic and natural features). The fundamental idea

is a holistic rather than a fragmentary engagement with the task

of managing resources. There is, after all the analysis, just one

environment – not several. The urban and the natural are not as

distinct as traditional thinking has assumed.

The third and last pillar, cities with the social and institutional

capital for sustainability, resilience, and liveability, stands united

with the other pillars and in contradiction to superseded ways of

thinking; but it demands a more extended explanation. While cities

have long been condemned as alienating and alienated – prone to be

characterized as inhuman blemishes on the landscape rather than as

centres for human thriving – we can with at least equal justification

celebrate, nurture and harness the social capital that is concentrated

in the modern city. Cities are not simply the problem; the modern

city’s emergent social properties make it a source of solutions. We

encountered precursors of this idea above: according to the first

pillar, cities have infrastructure that can be turned to use as new

water catchments; and according to the second pillar, the urban-

rural divide is best treated as artificial anyway, to be transcended for

human purposes as much as for ‘natural’ ones. We saw how WSUD

can work as a set of ‘urban design solutions’ for the provision of

green infrastructure. Now we must extend the idea. Technology

based on biophysical-science research alone cannot deliver, and

our appreciation of the crucial role institutions play in sustainable

resource usage is just beginning. We argue that unless new technol-

ogies are socially and institutionally embedded, their development

will not yield complete solutions for urban water management. The

social and institutional dimensions must be included in the holistic

vision too, on an equal footing with technological initiatives.

Insight in this area is elusive. The socio-institutional dimen-

sions of WSUD, necessary for effective policy development and

technology diffusion, need more research. Our anal-

ysis of the historical and socio-technical drivers of

WSUD development across Melbourne (a city often

identified as a WSUD leader, both nationally and

internationally, especially for stormwater manage-

ment) revealed that the deployment of WSUD in

Melbourne has been the result of a complex inter-

play between key ‘champions’ (or change agents) and

important local variables. In particular, the cham-

pions represent a small and informally connected

group of individuals across government, academia

and the development industry. These are the players

who have pursued change from an ideology of best

practice management, consistently underpinned

by local developments in science and technology.

Beyond the existence of champions, analysis revealed

the involvement of instrumental variables – a

mixture of historical accident and intentional advo-

cacy outcomes such as the rise of environmentalism,

external funding avenues and the establishment of

a number of industry-focused cooperative research

centres. The implications are well worth pursuing;

but it is important now to highlight sustainability,

resilience, and liveability – the desiderata mentioned

in connection with the third pillar.

Sustainability in the service of water sensitive cities

demands a solid reserve of sociopolitical capital, and

an assurance that citizens’ decision-making and behav-

iour are themselves water sensitive. It is a matter of

education in the broadest sense: the community must

value an ecologically sustainable lifestyle, with a

heightened receptivity to necessary innovations, and

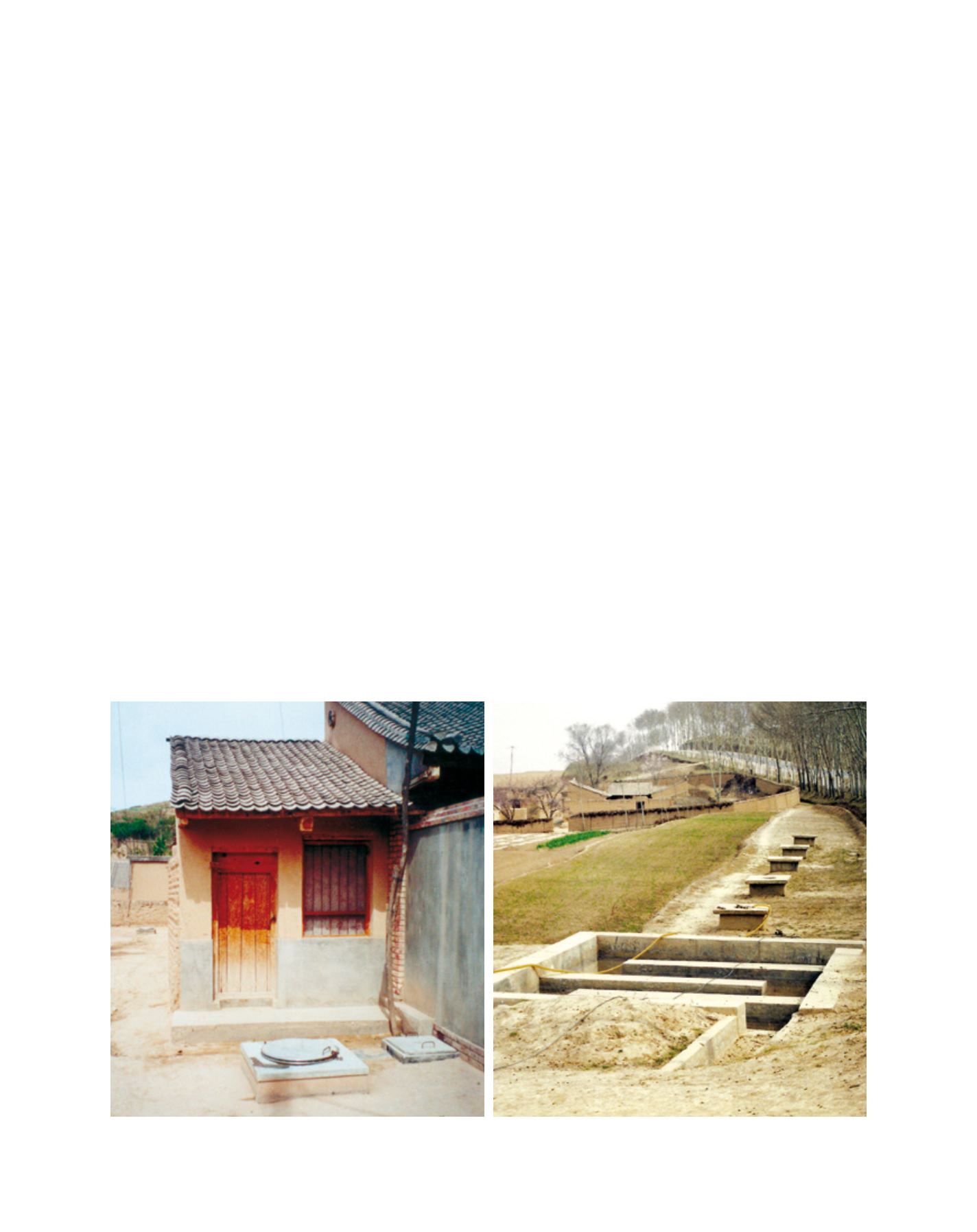

Harvesting rainwater (left) and harvesting road run-off in rural China (right) – simple ways for our cities and towns to serve as catchments

Image: Prof. Zhu Qiang and Prof. Li Yuanhong, Gansu Institute of Water Conservancy, China