[

] 275

Towards water sensitive cities:

a three-pillar approach

Tony H. F. Wong, Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities

W

hat is a water sensitive city? It is a city that interacts

with the hydrological cycle to provide the water secu-

rity essential for sustained economic prosperity – by

efficient and well-researched use of resources, including some

that have been overlooked by earlier generations of experts. It

is a city that enhances and protects the health of watercourses

and wetlands. It factors into all of its planning the risk of

looming drought and rising sea levels – and equally, the risk

of sudden and unforeseeable floods. Such a city creates public

spaces that harvest, clean and recycle water. Its management of

water contributes to biodiversity, carbon sequestration and the

reduction of urban ‘heat islands’. A water sensitive city is one

where water’s journey through the urban landscape is managed

with regard for its origins and its destinations – and where its

spiritual and cultural significance is celebrated. That city meets

challenges to the supply of life-giving water with integrity (not

evasion), breadth of vision (not the expedient perspectives of

sectional interests), and evidence-based practice (not slogans

from the past, nor borrowings from some imagined future).

What policies will yield these results? Three pillars

emerge to support such development – as affirmed by

research at the Cooperative Research Centre for Water

Sensitive Cities, an Australian Government initiative to

forge partnerships between research institutions and

industry, to find solutions to global challenges. These

three pillars are overarching principles for meeting the

challenge of developing sustainable and resilient urban

water systems:

• cities as water-supply catchments

• cities that provide ecosystem services

• cities with the social and institutional capital for

sustainability, resilience and liveability.

Far from being abstractions or mere theoretical under-

pinnings, these pillars respond to a real need for real

change. They are eminently practical. We accept as a

given the energy and the bursting vitality of modern

cities. That is not simply a part of the problem; it is also

a significant part of the solution – so long as the three

pillars are firmly established. And crucially, there are

implications for less developed cities.

The first of our three pillars, cities as water-supply

catchments, stands in direct opposition to the tradi-

tional model in which a city’s needs are passively served

by catchments external to it. Cities typically depend

exclusively on the capture of rainfall run-off from rural

or forested catchments and/or on depleting groundwater

resources; but the evidence is that such a one-way trans-

action is far from optimal. It is certainly not sustainable

as a universal solution. Communities become hostage

to increasing temperatures and drying soils – prob-

lems that are all the more pressing because of ‘normal’

climate variability, progressively worsened by the

reality of long-term climate change. Reflex reliance on

the conventional approach (“just build another dam”)

is no longer sufficient. The effects of climate change

are uncertain, and rainfall is not invariably reduced.

But overall, it is established that global temperatures

continue to trend higher. Drier catchments are no

longer a feature of one projected future among many;

they are an inevitability. And drier catchments mean

decreased run-off. Our precarious dependency on soil

moisture in external catchment areas has to be broken.

This situation calls for a radically new model. Cities

themselves have enormous potential as catchments,

E

conomic

D

evelopment

and

W

ater

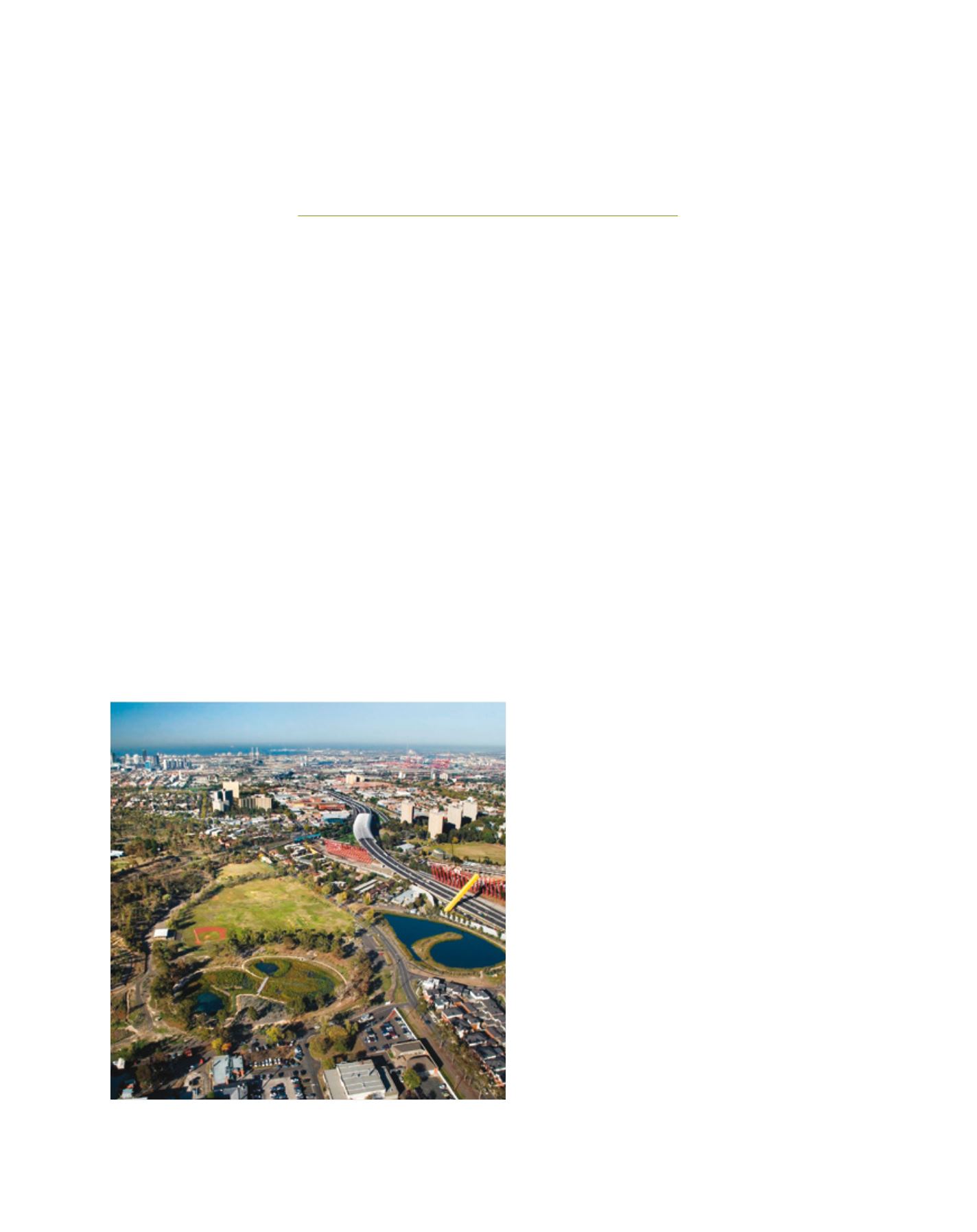

Our cities are water supply catchments – as illustrated by the Royal Park Wetland in

Melbourne, used for harvesting and treating urban stormwater

Image: Tony H. F. Wong