[

] 285

E

conomic

D

evelopment

and

W

ater

65 hm

3

while 6.2 hm

3

is for livestock, 440 hm

3

for agriculture, 0.9

hm

3

for olive mills and 3.2 hm

3

for industrial purposes. Around the

half (46 per cent) of the total water requirement is requested by

the Irakleion prefecture. The available water volume on an annual

basis is estimated to be 372 hm

3

, leaving a water deficit of about

143 hm

3

. Increased water demand for agricultural use on the island,

(approximately 85 per cent of water use) cannot always be met.

10

Great efforts have been made to promote rational use of water by

the agricultural sector, even though irrigated water exceeds 500 mm

annually (a mean rate for agriculture).

Groundwater resources in Crete are overexploited, especially in

the Messara aquifer in South Irakleion where an estimated 51 hm

3

of water is extracted each year, exceeding aquifer yield by 10 hm

3

.

11

Nowadays water needs are covered by a dense network of pipes that

transfer water from springs, reservoirs and groundwater bodies to

villages and coastal cities. For instance in the Rethimno prefecture

the Potami dam, with a reservoir capacity of 23 hm

3

, covers the

irrigation needs of the Amari valley. A substantial amount of water

is reused and becomes available for agricultural and urban needs.

Eight of the 18 domestic wastewater treatment plants in Crete reuse

water to satisfy agricultural water needs. In addition, during recent

years, desalination technology has started to be used for obtaining

small quantities of water for domestic supply, although this is recog-

nized as a very expensive solution.

Issues of water management, spatial planning and agriculture were

historically administered by distinct organizational bodies such as

the Eastern Crete Development Organization and the Western Crete

Development Organization, the municipalities, water associations

and several local land reclamation services without any coopera-

tion between them. The main problem was that the western part

of the island experiences water surplus and the eastern part suffers

from water deficit, but the administrative structures were not organ-

ized in a way that allowed water transfer from the one part of the

island to the other. Many environmental problems have arisen due

to water deficit, such as seawater intrusion into the coastal aquifer,

river dryness, lowering of groundwater levels in many valleys, and

related ecological problems such as the loss of endemic

biodiversity and increased salinity of fresh water. Cretan

wetlands are currently under threat due to overexploita-

tion of water resources. Coastal marshes in particular

are endangered as a result of the expansion of urban

and touristic settlements.

12

In order to minimize the

water shortage problem, effective cooperation is neces-

sary among the different water use sectors, as well as

among the communities which belong to different

basins. Especially in cases where hydraulic works have

to be conducted for transferring water from one region

to another, approaches are needed to convince the local

communities involved.

In the past, environmental issues arising from

water management were not acknowledged as the

main responsibility of any water-related organiza-

tion. However, the adoption of the European Union

Water Framework Directive in national legislation

ushered in the creation of water districts. Crete is

recognized as WD13 and the responsibility for water

management belongs to the Water Department of the

Decentralized Administration of Crete. The prepara-

tion of river basin management plans and suggested

programmes of measures are under public consulta-

tion at the time of writing, especially actions focused

on preventing drought, which Crete faces quite often,

and flood. Public participation is a prerequisite in all

stages of management plan creation, so all interested

parties are actively involved. Even water authori-

ties which were inexperienced in participatory and

cooperative forms of governance have supervised

several stakeholder groups. The main outcome of

this participatory process has been effective linkages

between the various water use sectors. Some forms of

interaction and cooperation were generated between

associations managing irrigation water and public

water supply services. Public awareness resulted

in a deeper understanding of water issues,

13

allow-

ing water allocation from the west to the east part

of Crete. Current policies identify the maintenance

of domestic and municipal water supply as the first

priority, followed by agricultural needs. Perennial

crops are the first priority of the agricultural sector,

ahead of seasonal vegetables.

Towards sustainable management

Crete is moving towards the sustainable management

of existing water resources with the aim of achieving

maximum yields and optimal utilization. Balancing

demand and supply is an important goal in light of the

limited available resources and growing demand in the

urban and touristic sectors. Measures such as managed

aquifer recharge, village connections to wastewater

treatment plants, river ecological flow, erosion elimi-

nation and flood control should be taken to prevent

ecological problems. Cooperation among the different

water use sectors and the communities which belong to

different basins will help to minimize the water short-

age problem.

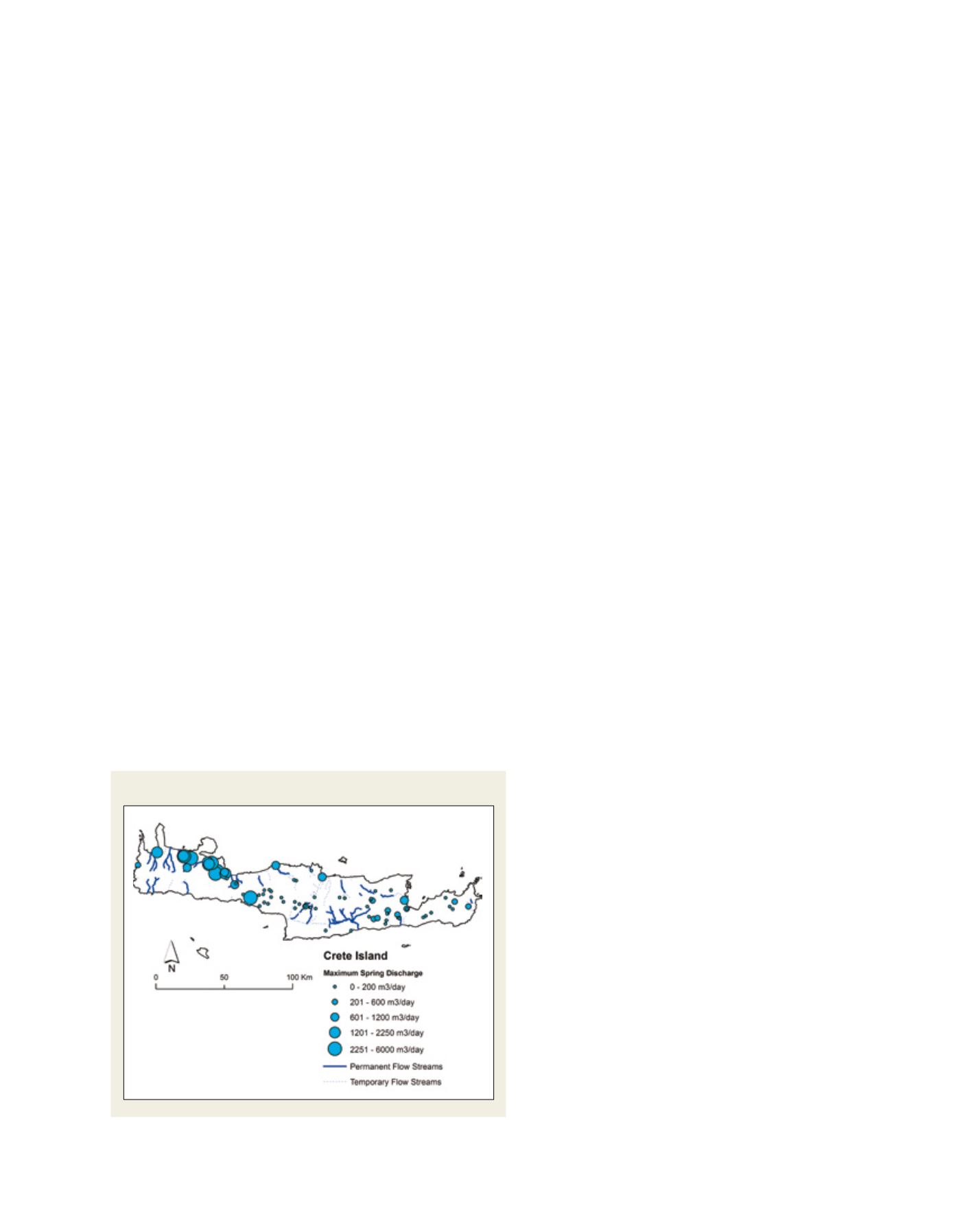

The main springs in Crete and their maximum recorded discharge

Source: IGME, Water Points Recording – Crete Water District (2009)