[

] 289

I

nternational

C

ooperation

on

W

ater

S

ciences

and

R

esearch

nical and managerial, were often applied to very diverse

locations, irrespective of whether or not they fitted the

specific situation. The most influential paradigm for the

cooperative management of water resources today, namely

Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM), is a

great step towards integrating complexity in water manage-

ment. However, the priorities for implementing IWRM are

still often generalized, without explicitly taking differences

into account. For instance, setting up integrated river basin

management plans might not be practicable for countries

with limited institutional capacities.

This discrepancy between theory and feasibility in

implementation is one reason why IWRM has fallen short

of initial expectations. To overcome these difficulties,

one has to examine the potential forms of cooperation

which are best suited in different settings while taking

into account that the values and priorities associated with

water and development vary tremendously between socie-

ties. Therefore, the relevant issue is to identify the factors

and circumstances that induce or encourage cooperation.

While the public debate over competing needs and

demands for international water resources largely

focuses on the extreme of ‘water wars’ as opposed to

‘water cooperation’, there is a much wider variety in

the forms and levels of potential cooperative behaviour

between actors than those two aspects. The spectrum

of cooperation ranges from sharing data and infor-

mation to the joint management of a water resource.

Especially in the case of transboundary rivers, one

has to recognize that the benefits for nation states

do not necessarily increase with the level of coopera-

tion.

4

Cooperation also comes at a cost, and there is a

need to identify conditions where the benefits of such

cooperative behaviour outweigh its costs. The poten-

tial costs and benefits also depend on physical, social

and economic factors which differ from basin to basin.

However, little is known about how water governance

and management systems perform in different socio-

economic and environmental contexts.

To close this gap, the Twin2Go project endorsed by

GWSP conducted a comparative analysis of complex water

governance and management systems in 29 river basins

around the globe. It was found that forms of governance

with polycentric cooperative arrangements show the best

performance – that is, those governance structures which

favour the sharing of power between different centres

without losing the coordination between them. The

distribution among several centres enables more flexible

responses that fit the specific situation and place of action,

which makes it easier to deal with uncertainties.

Such studies can help to make adaptive governance

of river basins work in the sense of an IWRM. However,

IWRM conceptually assumes cooperative behaviour

between stakeholders without further questioning

whether cooperation actually exists, or whether it is desir-

able for a certain actor. Cooperation is a prerequisite for

good water governance but it cannot be taken for granted.

While new theories in economics have shown that the

exploitation of shared resources, in the sense of a Tragedy

resources, and the sharing of information and data on all levels –

including the global scale.

For instance, a recent GWSP study

3

on global threats to human

water security and river biodiversity found that almost 80 per cent

of the world’s population faces high levels of water security threat.

Immense technological investments enable rich states to counterbal-

ance these threats without acting upon the root causes, whereas less

wealthy countries remain exposed and vulnerable. Similarly, biodi-

versity is jeopardized by a lack of preventive action. The framework

developed by Charles Vörösmarty, and others, helps to prioritize

potential cooperative responses to this crisis in terms of policy,

management and governance.

From a governance perspective, new forms of multidimensional

cooperation are needed – between sectors of industries and services,

between and within nation states and non-governmental institutions

– to provide water security for everybody, without jeopardizing the

natural resource base on which the world depends.

However, while it is easy to call for cooperation, in reality, effective

and sustainable cooperation on the management of resources can be

hard to achieve. This is particularly the case when adequate knowl-

edge of the processes needed to establish such cooperative behaviour in

different settings is lacking. In the past, universal remedies, both tech-

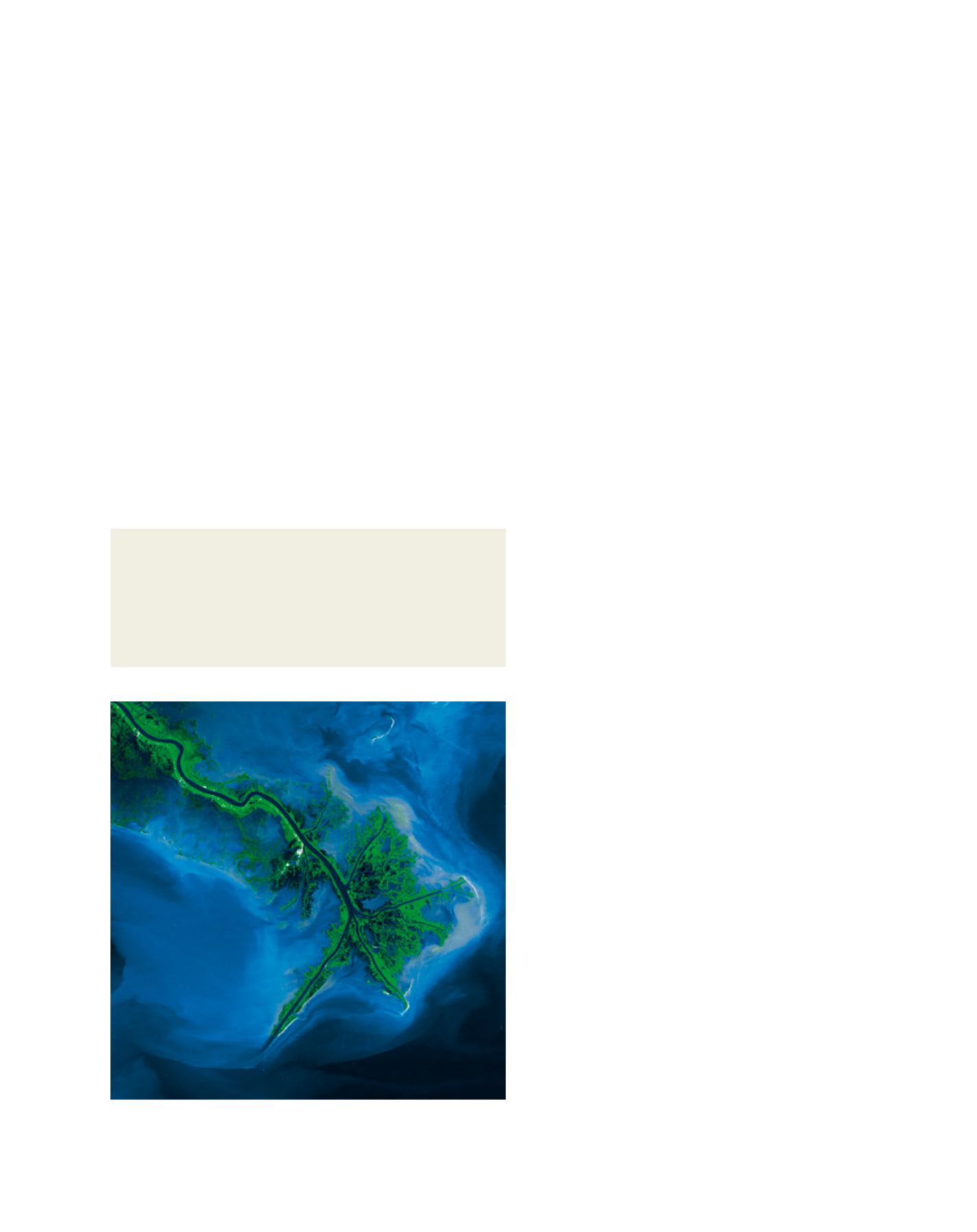

Global assessments are needed to properly understand anthropogenic and

environmental changes in the water cycle

Image: NASA

The Bonn Declaration on Global Water Security

The water community assembled in Bonn for the GWSP Conference “Water

in the Anthropocene” in May 2013, urged a united front to form a strategic

partnership of scientists, public stakeholders, decision- makers and the

private sector. The declaration calls for more cooperation in order to

develop a broad, community-consensus blueprint for a reality-based, multi-

perspective, and multi-scale knowledge-to-action water agenda.