[

] 62

T

ransboundary

W

ater

M

anagement

In the 1990s, environmental degradation saw a

1,000 km-long toxic blue-green algae bloom in the

Darling River system and increasing algal blooms

throughout the whole Murray-Darling Basin.

Increasing water demand was also contributing

to rising water salinity, declining biodiversity and

less frequent beneficial flooding in floodplains and

surrounding streams. Recognizing this, govern-

ing jurisdictions agreed to cap their allocations for

consumptive use from the system at 1994 levels. The

cap meant that new surface water demand could only

be satisfied through trading. This important policy

decision recognized that the limits of sustainability

had been overreached.

This period was also marked by significant micro-

economic reform in Australia and water became part of

that broader appetite for national change. In 1994, all

governments committed to the Council of Australian

Governments Water Reform Framework, which was

designed to make water management more environ-

mentally sustainable and economically efficient. The

key elements of subsequent reforms were founded

in that agreement. They included recognition of the

water needs of the environment, handing irrigation

systems over to irrigators to manage, tradable water

rights, and the separation of the regulatory, policy and

service delivery functions of water authorities.

In the 1990s the nation began to feel the effects of

what would become the 12-year-long ‘Millennium’

drought, triggering a renewal of focus on effective

management of Australia’s resources. In some commu-

nities, the drought came close to putting water for basic

Australia, like other countries, faces increasing pressures for water

to be made available for productive agriculture, economic growth,

the growing needs of cities and the environment. Not only are the

demands on water resources escalating, but a changing climate

means that in many regions there is less water to go around.

Managing water and supply security in Australia is a shared

challenge. It has many players, very different local circumstances

and no single government agency has sole authority.

Unlike international transboundary water issues that focus on

intercountry negotiations, Australia’s transboundary water issues

are domestic – but no less complex. Under Australian water laws

it is not the federal government that determines the conditions on

which water is available for use, but the six state and two territory

governments. Local government also has an important role in water

delivery, stormwater and drainage, which increasingly feature in

urban supply and demand management.

Yet there are national imperatives for water management. Most

notably in Australia, these have been to share physical water

resources among states, to protect nationally significant environ-

mental assets and to foster interstate water markets. Attempts to

achieve these goals have been complicated by different legislative

and administrative arrangements between states, and by the different

character of hydrological systems and water-dependent ecosystems

both within and between states.

Following the federation of Australia’s states in 1901, initial

steps towards intergovernmental cooperation on water resources

focused on developing water supply systems and increasing water

storage capacity. By the 1980s, the limitations of this approach were

being observed in many parts of rural Australia – with diminishing

returns on subsidized infrastructure, rapidly rising water extrac-

tion challenging the capacity of water systems, and increasing and

obvious environmental degradation.

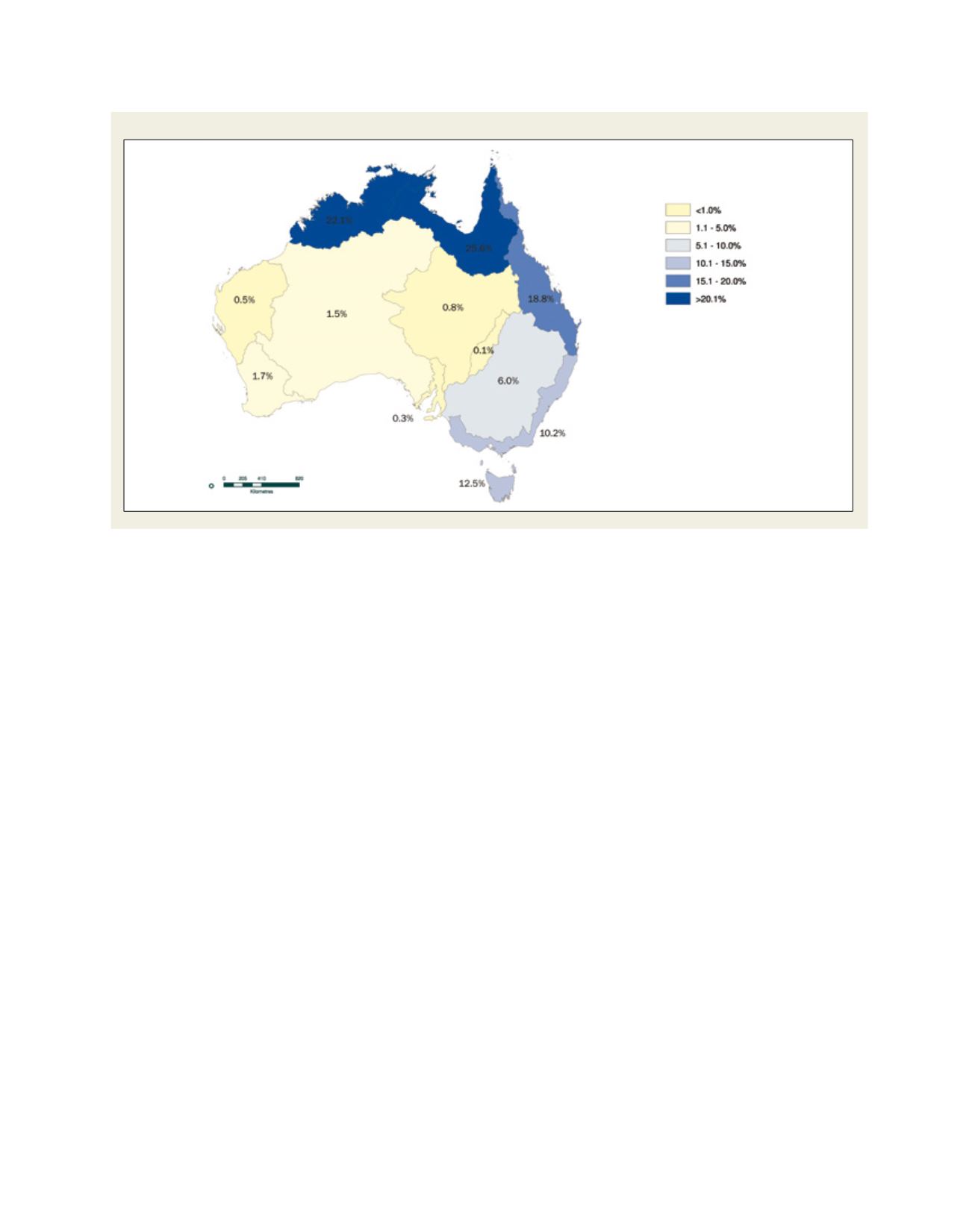

Distribution of Australia’s mean annual run-off

Source: Water and the Australian Economy, April 1999