[

] 120

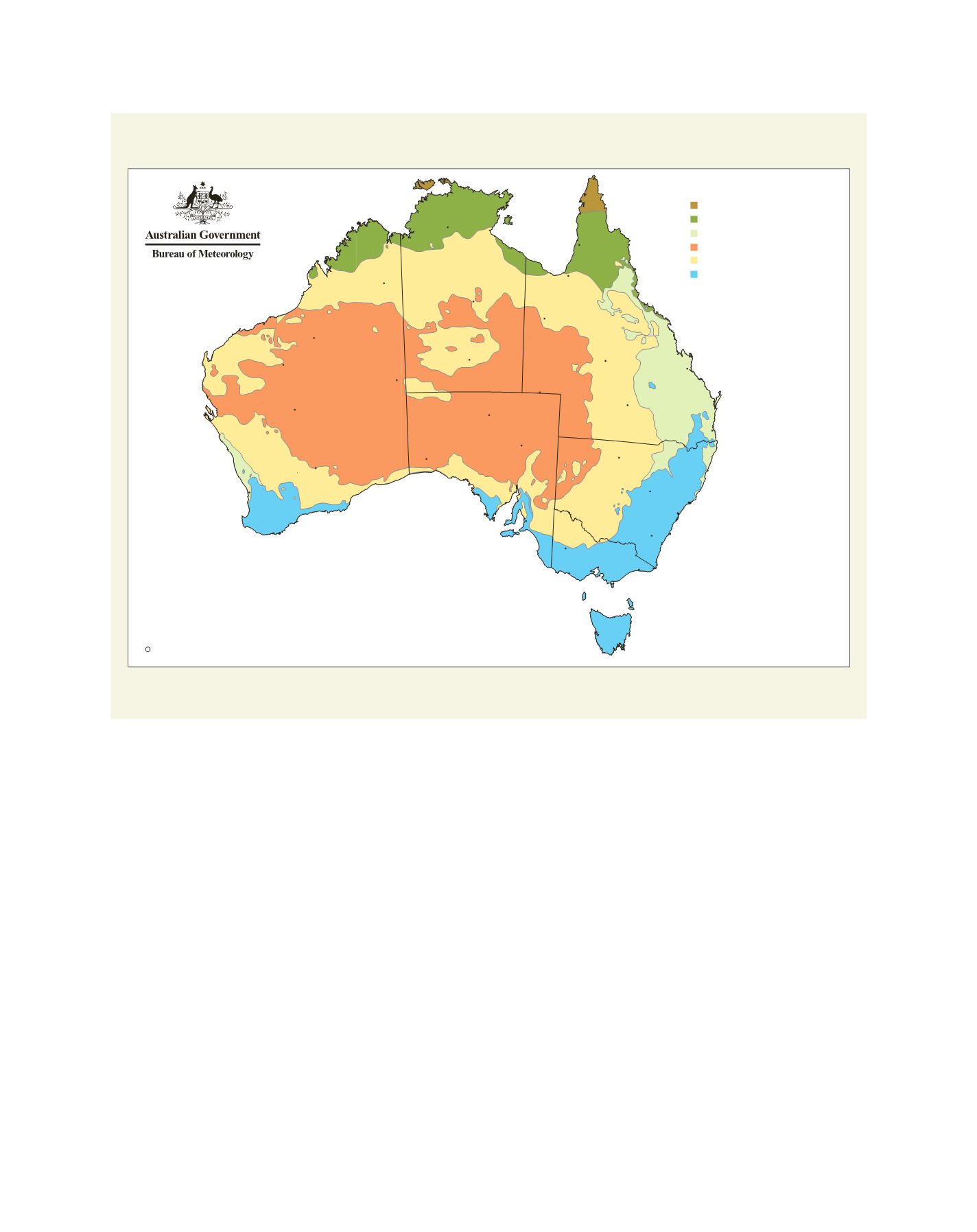

Australia’s climate zones: just over two-thirds of mainland Australia is classified as arid or semi-arid

Based on a modified Koeppen classification system

Based on a standard 30-year climatology (1961-1990)

Commonwealth ofAustralia, 2005

c

Projection: Lambert conformal with standard parallels 10 o S, 40 o S.

Geraldton

PERTH

Albany

Carnarvon

Port

Hedland

Wiluna

Telfer

Broome

Kalumburu

Halls Creek

Giles

Kalgoorlie-

Boulder

Esperance

Port

Lincoln

Port

Augusta

Ceduna

ADELAIDE

Marree

Oodnadatta

Alice Springs

Tennant

Creek

Katherine

DARWIN

Cook

Weipa

Kowanyama

Cairns

Townsville

Mackay

Normanton

Mount Isa

Birdsville

Mildura

Horsham

MELBOURNE

Warrnambool

Orbost

CANBERRA

SYDNEY

Dubbo

Coffs

Harbour

BRISBANE

Charleville

Rockhampton

Longreach

Bourke

Cape Grim

St. Helens

HOBART

Strahan

Newman

Subtropical

Desert

Grassland

Temperate

Tropical

Equatorial

Major classification groups

Source: BoM

As the land dries and these regions become vulnerable to

increased desertification, salinity becomes an even greater

issue. Since European settlement, native land clearance,

farming and irrigation have created an imbalance in the

hydrological cycle in many agricultural areas, with rising

groundwater resulting in severe dryland salinity.

In 2000, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) esti-

mated that 5.7 million hectares of Australia was at high risk

of developing salinity. This could triple to about 17 million

hectares by 2050, seriously impacting agriculture, ecosys-

tems and infrastructure.

The vital role of groundwater in the Australian economy

will become more critical as surface water becomes scarcer

in arid and semi-arid regions. Its importance was high-

lighted in a 2014 report commissioned by the National

Centre for Groundwater Research and Training (NCGRT)

in the first attempt to quantify its value.

The report, by Deloitte Access Economics, found that

groundwater helps earn the nation a conservatively estimated

$A34 billion every year. It estimated annual groundwater

extraction at approximately 3,500 gigalitres, with 58 per cent

used to grow food, 12 per cent for mining and 17 per cent

used in manufacturing. About 13 per cent is used for water

supplies in regional and metropolitan communities.

Pressure on Australia’s groundwater reserves is also inten-

sifying as the population increases. Australia has the fastest

population growth of any major developed country due to

immigration — and it shows no signs of slowing. Currently

standing at 24 million, ABS says Australia’s population could

double to 48 million people by 2061.

The key question that needs answering now is how such

rapid growth, combined with the uncertainty of climate

change, will impact on our water systems and the countless

industrial, agricultural, community and environmental users

that rely on them. There are no large water sources still to be

found in Australia, yet water use is expected to at least double

by the middle of this century.

Managing the cumulative environmental impact of multiple

actions on the baseflow of rivers, springs, wetlands and other

groundwater-dependent ecosystems is a huge challenge. The

task becomes even more complex when a growing population

and extreme weather patterns are added to the equation.

An estimate widely accepted by scientists and policy-

makers is that groundwater directly supplies more than

L

iving

L

and