[

] 135

leading cause of land degradation. In practice overgraz-

ing is poorly understood and frequently misrepresented,

and in a number of cases under-grazing is an equally

important issue. Many rangeland ecosystems depend on

herbivore action to maintain specific plant communities

and when this action is disrupted, degradation processes

can be triggered. Grazing mismanagement practices are

a common outcome when herd management and seasonal

herd movements are restricted. Policies and strategies of

sedenterization, the loss of transhumance corridors, or

inappropriate location of water points contribute to this

outcome. Such mismanagement can become common prac-

tice across a rangeland landscape when small but critical

resource patches are rendered inaccessible (for example

dry-season grazing areas converted to croplands, or forest

patches fenced off to create protected areas).

5

Sustainable land management (SLM) plays a vital role

in halting land degradation and in rehabilitating degraded

lands. Many countries face the challenge of maintain-

ing long-term productivity of ecosystem functions while

increasing productivity of food and other ecosystem

services. This also applies to sustainable range management

(SRM), a term we adopt to cater for the specific conditions

of rangelands.

Sustainably managed rangelands can also deliver impor-

tant benefits through ecosystem services — such as water

cycling or climate regulation — which have knock-on effects

on populations locally and externally. Improved rangeland

hydrological cycles lead to better infiltration of water and

reduced surface flow, which contribute to fewer floods and

lower risk of drought. Indeed each action that takes place in

the rangelands has an impact on surface and groundwater.

6

The hydrological cycle in rangelands can be characterized as

providing irregular water inputs that are dependent on irreg-

ular rainfall patterns and, in general, regular water outputs

in the form of regular flows of surface and groundwater. On

the basis of these water outputs other ecosystem services

can be provided as a function of the health of a rangeland

ecosystem.

7

These can include higher biodiversity, soil fertil-

ity, carbon sequestration, quality of drinking water and its

health benefits, and maintenance of rangeland products like

fodder that are the basis of the pastoral economy.

Recent studies have suggested that soil carbon manage-

ment presents the most cost-effective climate change

mitigation option.

8

Rangelands (including grasslands,

shrublands, deserts and tundra) contain more than a

third of all the terrestrial above-ground and below-ground

carbon reserves.

9

With improved rangeland management

they could potentially sequester a further 1,300-2,000

MtCO2e by 2030.

10

This is confirmed by research estimat-

ing that 51 per cent of the global 2011 net carbon sink

was attributed to the three Southern Hemisphere semi-

arid regions. The higher turnover rates of carbon pools in

semi-arid areas make rangeland ecosystem dynamics an

increasingly important driver of global carbon cycle inter-

annual variability.

11

Good practices in rangeland management thus offer

win-win situations for simultaneous economic, social and

environmental benefits. Moreover, sustainable land manage-

ment in rangelands has the potential to provide multiple

benefits not only to communities that directly depend on

rangelands but also to others: neighbouring rural commu-

nities, urban centres and global society. At the same time

sustainable range management can be an important vehicle

to contribute to land degradation neutrality (LDN).

In the many cases where pastoralism is practiced unsus-

tainably, the common response is to intensify land use,

notably by converting rangeland to croplands. However,

land use intensification is driving investments away from

the multiplicity of benefits from ecosystem services towards

a narrower focus on single benefit streams. At the same

time, such conversion bears the multiple costs of land

degradation, degradation of watersheds, reduced biodi-

versity, increased poverty, social inequity and release of

greenhouse gasses, as well as concomitant costs of land and

biodiversity restoration or rehabilitation.

Sustainable rangeland management

SRM should focus on enhancing the resilience of rangeland ecosystems

in view of the high variability and unpredictability of precipitation,

which is likely to be exacerbated by climate change. Much can be

learned from local customary practices that have developed indigenous

livestock breeds and management systems, which demonstrate

remarkable adaptation and tolerance and are often critical to the

efficiency of the system. Indeed, a frequent feature of indigenous

SRM technologies is their orientation towards ensuring productivity

in the worst years rather than maximizing on the good years. In lands

where drought is the norm rather than the exception this is a logical

adaptation and is central to resilient rangeland livelihoods. However,

this age-old ecological insight can be easily jeopardized by a myopic

focus on maximizing production in the short-term, and especially

through use of unsuitable land use and cropping strategies.

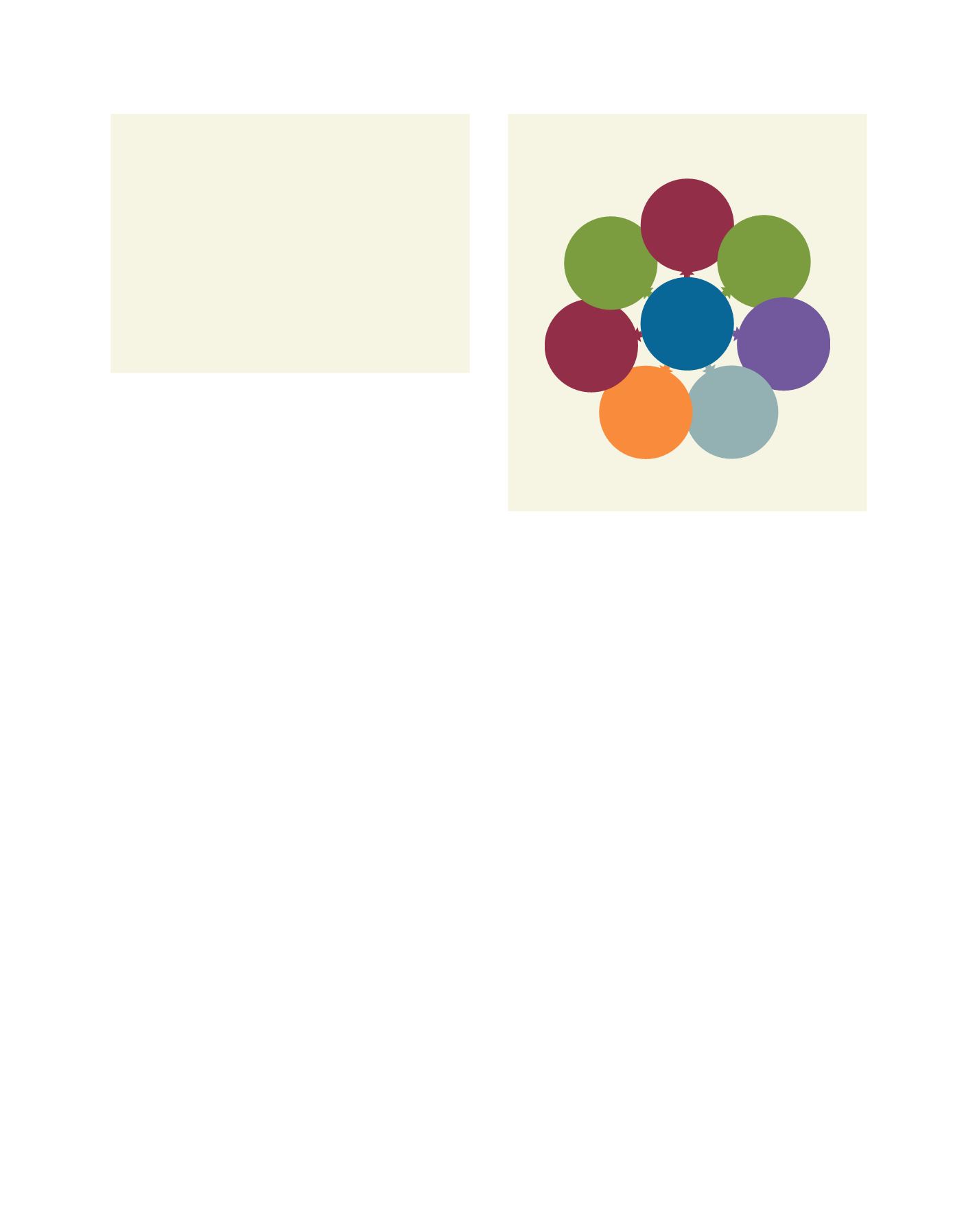

Multiple benefits of sustainably managed rangelands

Maintaining

hydrological

cycles and

protecting

watersheds

Disaster risk

reduction

Climate

change

adaptation

Sustainable

rangeland

management

Carbon

sequestration

and climate

change

mitigation

Biodiversity

conservation

Food security

Economic

growth and

poverty

reduction

Source: Adapted from McGahey et al, 2014

12

L

iving

L

and