of trees is banned through religious sentiments. This

approach was demonstrated in the restoration of Badrivan

in Badrinath — a famous Hindu shrine at high altitude

in Uttarakhand,

7

and Raksha Van (a defence forest) estab-

lished by army people in 10 hectares of land at Bantoli

(Badrinath). Also, at Kolidhaik village (Champawat district,

Uttarakhand) 5.6 hectares of degraded land was brought

under plantation of 6,200 saplings of 20 MPTs which have

attained over 3-4 metres in height. This approach was

included by the International Union for Conservation of

Nature in its guidelines for planning and managing moun-

tain protected areas.

8

It can be inferred from the above mentioned case studies

that owing to the great biophysical diversity of the IHR a

range of approaches would be required to address waste-

land rehabilitation/restoration and stop further degradation

of land. Some of the major recommendations drawn from

our studies are to:

• strengthen village institutions as they comprise

crucial traditional knowledge on natural resource

management; the best practices must be scaled up

• promote participatory consultation with communities

to share knowledge, beliefs and resources for

rehabilitation of degraded land

• emphasize ecological, agroecological, and

socioeconomic considerations

• develop strong linkages among technical institutions,

village institutions, practitioners and policy planners

• strengthen formal and technical information networks

on land rehabilitation engineering, erosion control

measures and productivity enhancing techniques

• include religions and cultural/economic/livelihood

concerns in rehabilitation activities and incentives for

participation

• facilitate community skill development and training on

key sectors of ecological rehabilitation of wastelands.

tion (0.95-2.09 t C/ha

-1

/year

-1

), and fodder harvest (14.4 t/

ha

-1

) was recorded. Vegetables grown in this demonstration

site were consumed and sold by the stakeholder fami-

lies.

5

Similarly, in Dharaunj (14 ha) and Gumod (6.5 ha)

villages of Champawat district (Uttarakhand) cash crops

of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) were planted and

capacity-building of farmers on cultivation, harvesting, value

addition, packaging and marketing of MAPs was undertaken.

Income generated from

Ocimum basillium

(Rs98,500 per

hectare) encouraged 120 farmers to adopt MAPs for income

generation and a benefit-sharing mechanism was devised by

forming a MAPs growers group.

In the shifting cultivation (jhum) affected area in the

north-eastern IHR, extreme soil erosion and loss of soil

fertility has accelerated the pace of land degradation and

reduced crop yield. In such areas contour hedgerow inter-

cropping was practiced, which involved the planting of

local leguminous nitrogen fixing shrubs at 1.5 m to 2 m

distances (the alleys) along contours. Crops were grown in

the alleys by applying a mulch of these hedgerow species

to improve soil fertility (nitrogen from 0.165 per cent to

0.173 per cent) and yield of vegetables (20 per cent to 100

per cent). Soil erosion was reduced to 50 per cent after

three years.

6

Eco-restoration of degraded forest land:

Mobilizing people

for plantation of degraded forest lands in the high alti-

tudes is rather a tough task as this land is owned by the

Government and people often do not consider themselves

to be the real stakeholders. In such land, the creation of

sacred forests and integration of science with religion was

adopted as an innovative approach for inviting the partici-

pation of the people. After eco-physiological scrutiny,

plants acclimatized for high altitude were distributed as

‘Briksha Prasada’ by the local religious authority to pilgrims

and local people, and were planted as an act of devotion.

The plantation is dedicated to the local deity, and cutting

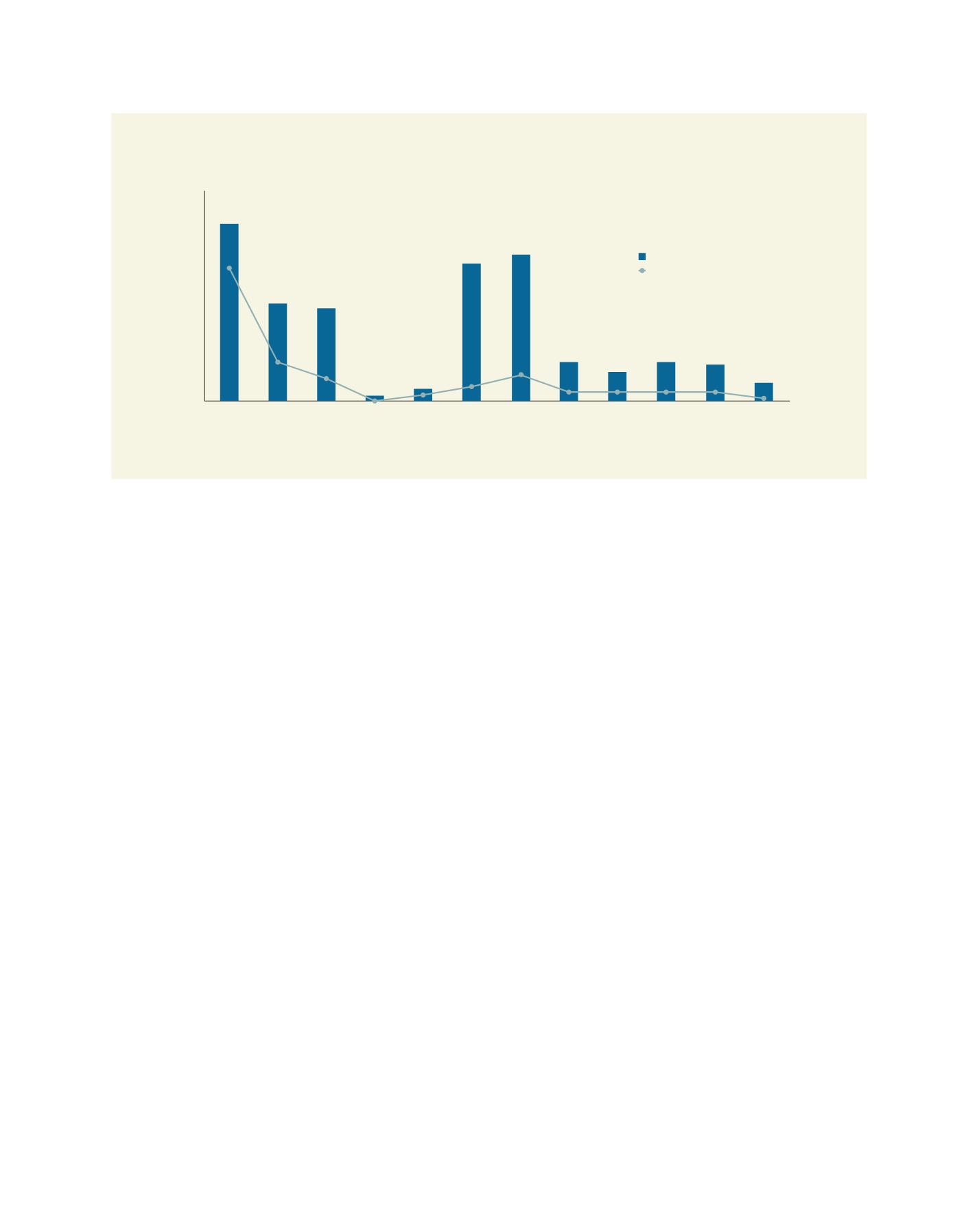

Total geographical area of different IHR states and their respective total wasteland area (for West Bengal only,

Darjeeling district is considered)

Source: Wasteland Atlas of India, 2011

120,000

Jammu

& Kashmir

Himachal

Pradesh

UttarakhandDarjeeling Sikkim Assam Arunachal

Pradesh

Meghalaya Nagaland Manipur Mizoram Tripura

100,000

80,000

60,000

40,000

20,000

0

Total wasteland 2008-09 (sq km)

Total geographical area (sq km)

[

] 162

L

iving

L

and