[

] 160

for subsistence living has left the degraded mountain slopes

devoid of vegetation and prone to soil erosion, landslides,

nutrient washout and invasion of weeds. This region

is faced with a vicious cycle between land degradation,

scarcity of natural resources, loss of biodiversity, food

insecurity, poverty and outward migration. Under these

circumstances land degradation is deepening and wasteland

is increasing. These issues need to be tackled to restore

biodiversity and ecosystem services for the revival of dwin-

dling agriculture and threatened livelihoods.

It is evident from the foregoing that a reconciliation of

the livelihood interests (immediate tangible benefits) of

local communities with concern for ecology and biodi-

versity (long-term intangible benefits) is of the utmost

importance for sustainable rehabilitation of degraded waste-

lands. Since its inception in 1988, the GB Pant Institute

of Himalayan Environment and Development (GBPIHED)

has followed several approaches/methods across the IHR

for rehabilitation of degraded watersheds and forests,

pastures/non-arable land and abandoned agricultural

land. Mobilization of stakeholder communities for micro-

planning, selection of suitable multipurpose tree species

(MPTs) based on ecological suitability and the indigenous

knowledge of the community, application of soil and water

conservation (SWC) measures such as contour trenches

(5-6 m long, 30-45 cm feet wide at 5 m intervals), filling

pits dug out for plants with fine soil along with farmyard

manure (20:80 ratio) and biocompost, participatory planta-

tion and aftercare were followed across all the wasteland

rehabilitation models, and are briefly summarized below.

Eco-restoration of degraded watersheds:

A package of

practices named ‘sloping watershed environmental engi-

neering technology’ was devised for treating five degraded

watersheds. This approach integrates SWC measures,

plantation of suitable MPTs for provisioning fodder and

fuelwood, biofencing and aftercare of plants along with

the introduction of low-cost, environment-friendly and

income-generating activities to boost the livelihood of local

people and thereby reduce their dependence on the forests.

Measures such as rooftop rainwater harvesting for house-

hold needs and increasing the water retention capacity of

watersheds were also areas of prime concern. This approach

was used in 55 hectares of degraded land in the Bhimtal

lake catchment area (Nainital district, Uttarakhand). A

total of 38,322 saplings of more than 20 MPTs were planted

on barren hill slopes, where they registered a 16-47 per

cent survival rate after five years. The highest growth

was recorded by

Alnus nepalensis

(211 cm height; 5.6 cm

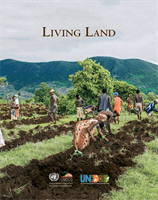

Plantation activities through women’s participation in a degraded community forest in Champawat

Image: GBPIHED

L

iving

L

and