[

] 165

The UNCCD’s 11th Conference of Parties in 2013 took the

first step in this direction by deciding to establish its Science-

Policy Interface, which started functioning as of June 2014.

This included motivating and assisting the Intergovernmental

Platform of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services to set and to

carry out a thematic assessment of land degradation and resto-

ration, whose findings would assist in guiding responses to land

degradation, including attainment of LDN at all scales.

One stumbling block for applying effective responses to land

degradation is that the UNCCD is directly relevant to only 34.5

per cent of global land since its mandate is restricted to drylands

only.

14

But loss of biological or economic productivity resulting

from processes spelled out by UNCCD text also occurs in most

of the other 64.5 per cent of global land, regardless of whether

it is exposed to risk of land degradation or desertification. For

example, land degradation in China depends more on land use

than on whether it is dryland or not. Other evidence of severe

land degradation in non-drylands is being increasingly detected.

15

In addition, non-drylands also abound in most ‘dryland coun-

tries’: only 43 per cent of these countries have drylands covering

more than 95 per cent of their territory, and in about third of the

dryland countries, drylands take up less than 50 per cent of their

territories.

16

Desertification national action plans compiled by

dryland countries, pursuant to their commitments as parties to

the UNCCD, address land degradation while ignoring the deline-

ation of drylands within their territories.

Furthermore, the climatic boundary of the drylands was set at

an aridity index value of 0.65,

17

that is to say areas where the ratio

of precipitation to potential evapotranspiration is higher than 0.65

do not qualify as drylands. The aridity index used for mapping

the global drylands

18

was based on the rainfall and tempera-

ture means for the period 1951-1980. However, the directional

anthropogenic climate change undermines the stability of the

aridity index and changes the spatial expase of the drylands. Most

of Africa, for example, has become drier: the hyper-arid and arid

drylands increased by 51 and 3 million hectares respectively, and

the non-drylands of 1931-1960, ‘lost’ 25 million hectares. Finally,

rainfall decreases and evapotranspiration increases are projected

to intensify this trend in many drylands by mid-century.

19

Thus,

lands identified as non-drylands due to their climatic conditions

during 1950-1980 already qualify, and many more will qualify as

drylands in the future, making the current distinction between

the UNCCD drylands and non-drylands redundant.

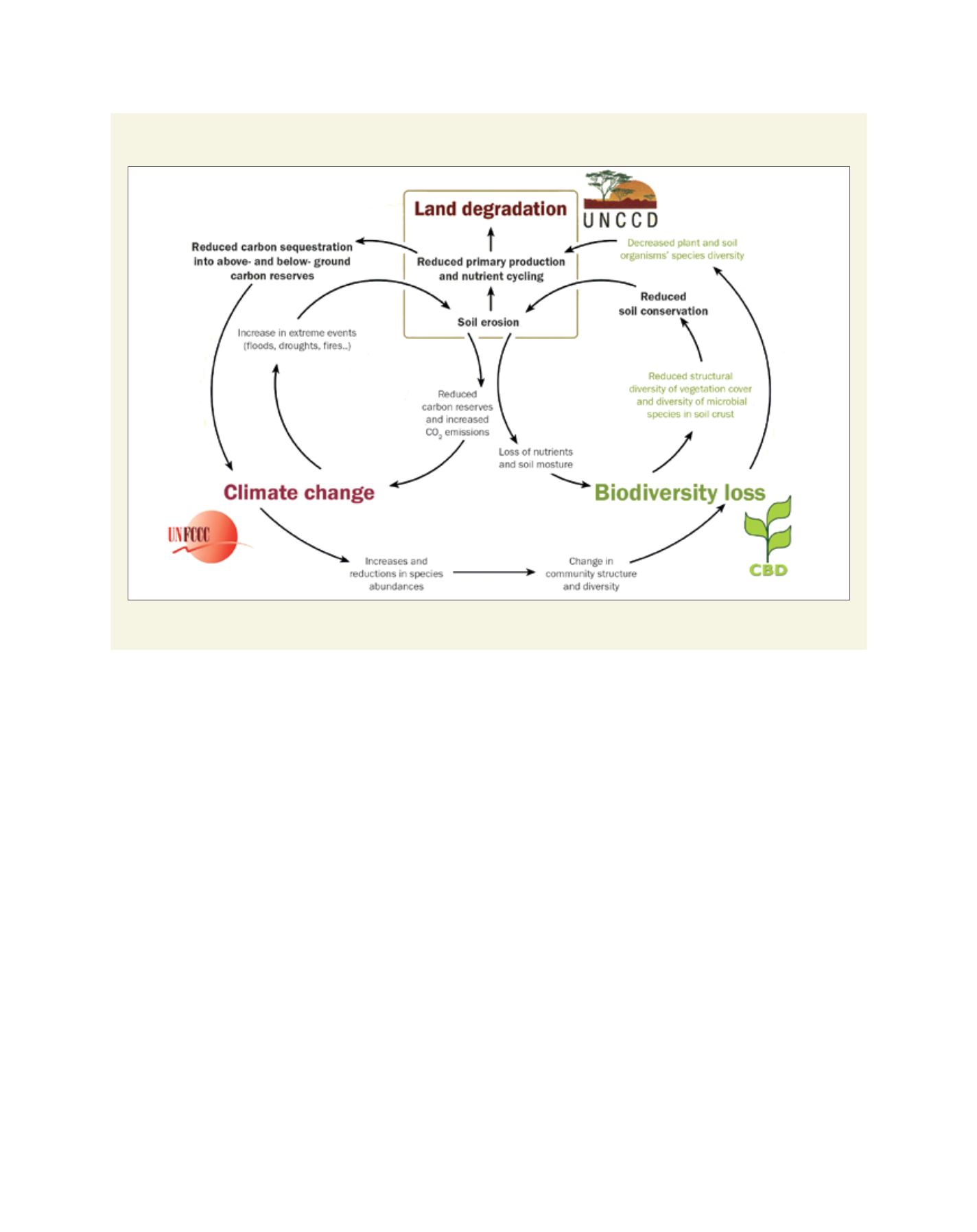

Finally, recalling that land degradation impacts biodiversity

and exacerbates global climate change, expanding the focus of

UNCCD to cover all lands and their soils would also enable the

addressing of land and soil issues at the global scale. Jointly with

the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change, addressing the land-

biodiversity-climate interlinkages would comprise an effective

framework for holistically securing the living land’s life-support

system of the planet.

Land degradation, climate change and biodiversity loss are mutually reinforcing nested feedback loops

Source: Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Adapted from Adeel, Z. et al, 2005

20

L

iving

L

and