[

] 163

Soil and the living land — threats and responses

Uriel Safriel, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research, Israel

S

oil constitutes the infrastructure for all terrestrial

life on Earth. Jointly, soil and the life it supports

make the living land, whose fertility caters for plant

productivity, which generates food for all other terrestrial

organisms, mankind included.

Soil provides mechanical anchorage and nourishment to the

land’s plant cover, which injects to the atmosphere the oxygen we

breathe, and absorbs atmospheric carbon dioxide thus regulating

the climate. Jointly with its underlying soil, the land’s plant cover

is engaged in water filtration and regulation locally, and in driving

the water cycle globally. The soil functions as a bioreactor for recy-

cling nutrients, as moisture and water storage, and as a repository

for organic matter that facilitates water-holding capacity, and its

sequestration contributes to climate protection. All these life-

support benefits to mankind travel across scales, from current to

future generations, from local to global land. But when the land

user inadvertently harms the soil of his land, the repercussions of

the resulting local fertility loss travel far, in time and space.

Loss of soil fertility is detrimental to the local land user,

hence local responses to prevent it are required. Direct users of

land productivity are often unaware of the losses or they lack

tools and resources for proper responses. The global indirect

users of soil fertility often possess the knowledge, technologies

and financial resources required by the local, direct land users.

Therefore, cooperation between the local direct and the global

indirect users of soil fertility would benefit both — it would

outweigh the short-term costs of using the soil prudently borne

by the local direct user, and the cost of international develop-

ment aid borne by the global indirect land user.

Themajor threat to soil fertility is when its exploitation, directed

at increasing land productivity that is of economic value, leads to

soil erosion, losses of organic and mineral compounds, and salini-

zation at rates faster than natural. Rather than the aspired increase

in economic land productivity, the land use practices bring about

a persistent and often irreversible productivity decrease relative to

the soil’s potential fertility. This persistent reduction in the land’s

biological productivity comes under the heading of ‘land degrada-

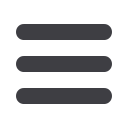

A Bedouin village in the Negev dryland of Israel: its degraded land due to ploughing (left) is a candidate for restoration; ongoing degrading land use (right) can be

offset when the degraded land has been restored

Images: Uriel Safriel

L

iving

L

and