[

] 155

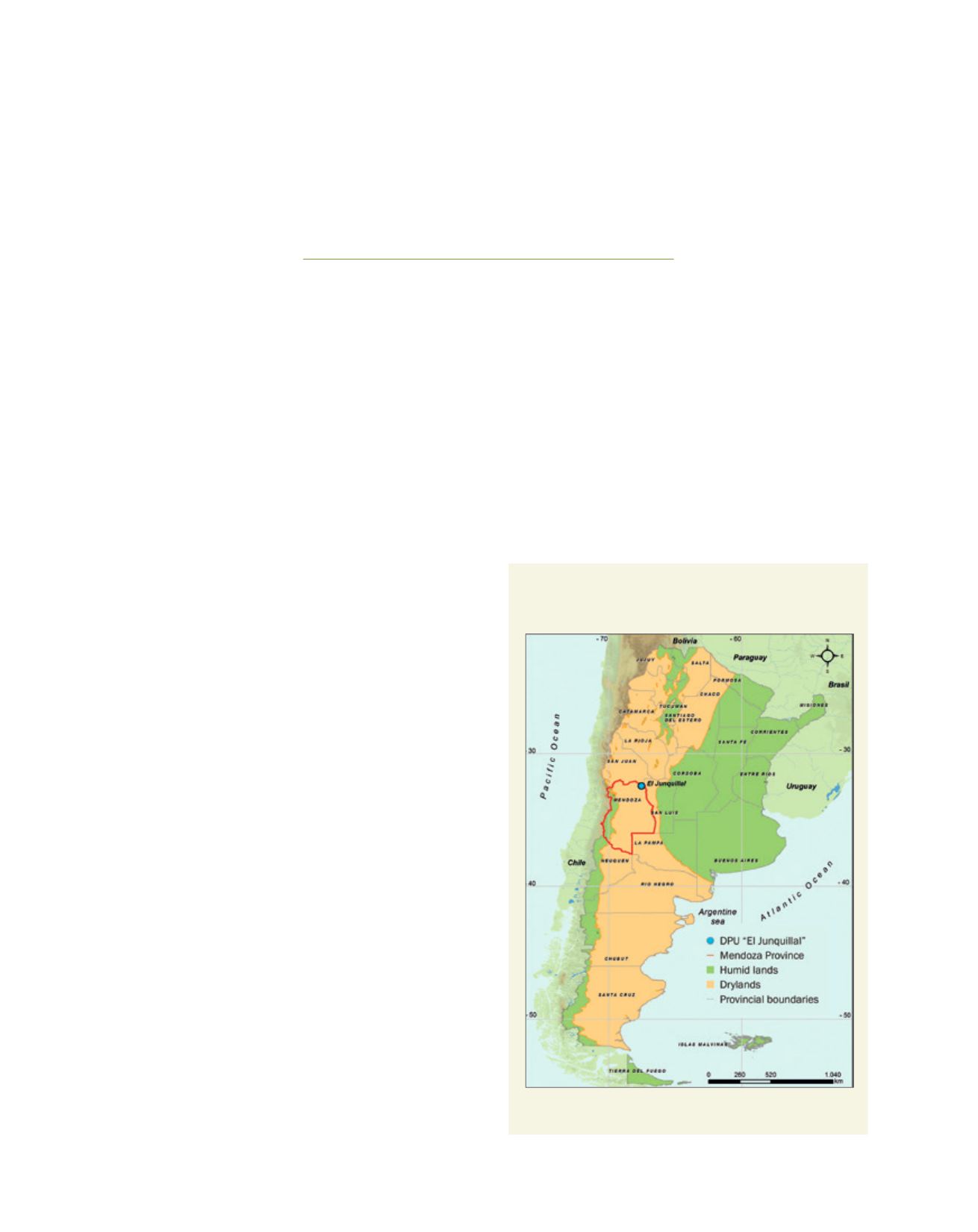

Recovering life in the desert: successful

experience with indigenous communities

in Mendoza, Argentina

Elena María Abraham, Laura Torres, Darío Soria, Clara Rubio and Cecilia Rubio, Argentine

Dryland Research Institute of the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research

The DPU experience involves active participation from

communities in the ‘El Junquillal’ locality of Argentina

Source: IADIZA

I

n contrast to the widespread image of Argentina as the

‘the world’s breadbasket’, reality shows a vast territory

(around 70 per cent) of dry, arid, semi-arid and dry

sub-humid lands affected by different degrees of desertifi-

cation. The Monte Phytogeographic Province makes up an

arid diagonal that crosses the country with all gradations

of aridity. This ecoregion, devoted to raising cattle and live-

stock, is the driest of cattle lands in Argentina. Agriculture

is confined to areas under intensive irrigation, the wine-

making ‘oases’. Both types of land use are responsible

for a great part of the degradation, evidenced not only by

biodiversity loss and deforestation of native woodland, but

fundamentally by the poverty of the people, most of them

subsistence goat herders who still remain in non-irrigated

drylands in extremely critical survival conditions.

1

Mendoza, with a surface area of 150,839 km

2

and a popu-

lation of 1,741,610 people, is located on the central strip

of Argentina’s drylands and 100 per cent of its territory

is desertified.

2

This territory is organized on the basis of

a great contradiction; the confrontation between irrigated

lands (oases) and the non-irrigated lands of the desert.

Competition for the use of water arises as one of the major

environmental conflicts in interaction between oasis and

desert: the latter no longer receives surface water inflows

because river flows are fully used for irrigating the culti-

vated area and for consumption in urban settlements. Hence,

non-irrigated drylands, which represent 96.5 per cent of the

territory, are characterized by very sparse population —

1.5 per cent of the total population — with a subsistence

economy based on goat production, and by their depend-

ence for equipment on distant urban centres. The desert has

lost its natural and social capital, which was used for build-

ing wealth in the oasis. Over time, it has offered valuable

resources such as mesquite woodland and grasslands, which

have been overexploited. The problems of land tenure, isola-

tion and marginalization of desert inhabitants have produced

strong exodus and migration movements. This involves

abandonment of productive lands and increased suburbani-

zation processes in the urban fringe.

The ultimate environmental problem affecting drylands is

desertification, triggered by climate variability and human

activities.

3

Despite the extent of Mendoza’s drylands, it

is essentially difficult to simplify the analysis of deserti-

fication because of the high diversity of socioeconomic,

political, ethnic and ecological situations taking place

throughout the area. Combating desertification is essential

to ensure long-term productivity of these drylands. Many

efforts have failed for using partial approaches, disregard-

L

iving

L

and