[

] 154

rainfall deficits during the millennium drought is the domi-

nance of high pressure. This suggests that the drought should

be considered, at least partly, as a shift to a more arid climate

rather than just an episodic drought event following which

conditions will return to the historical norm.

Even though the millennium drought is popularly consid-

ered to have ended during the 2010-2012 La Niña sequence,

there has been little recovery of cool season rainfall across

southern Australia. The period from late 2010 to early 2012

saw nearly continuous La Niña conditions in the Pacific result-

ing in the wettest two-year period on record for Australia.

However, the heavy rainfall was confined to the summer half

of the year, reinforcing the multi-decadal pattern of increas-

ing tropical (summer) rainfall in northern parts and poor cool

season rainfall in the south. With the return to near El Niño

conditions in 2014 and a subsequent El Niño in 2015, rainfall

patterns in southern areas and parts of eastern Australia have

returned to a situation similar to that which occurred during

the millennium drought. Preliminary data suggests that pres-

sure over southern Australia is likely to be above average in

2015, indicative that the background trend continues.

It remains to be seen whether the emerging impacts become

as severe as those felt during the millennium drought. Detailed

climate change projections for Australia show that contin-

ued rainfall declines are likely in the cool season in southern

Australia, and it is very unlikely that these will be offset by

summer rainfall increases. These changes will interact with

natural drought cycles and may be expected to give rise to

conditions beyond earlier experience.

Climate science and continued weather observations high-

light that recent dry periods across southern Australia are

more accurately characterized as a shift to an increasingly

dry climate (increasing aridity), rather than simply episodic

drought events. The poleward extension of the subtropical

dry zones and contraction of the westerlies is one anticipated

impact of a warming climate under the enhanced greenhouse

effect with ozone depletion enhancing this shift. These anthro-

pogenic drivers provide a causal mechanism for the changes

in pressure and rainfall in Australia’s south which continue.

While natural rainfall variability in Australia remains large,

and rainfall continues to be strongly influenced by the El

Niño Southern Oscillation, it is likely that the drying across

southern Australia in recent decades cannot be explained

by natural variability alone. When combined with increas-

ing temperatures and heightened demands for water, it is

imperative that managing for drought must look beyond the

past as a guide, and towards understanding the interaction

between climate variability and change to better inform deci-

sions for the future.

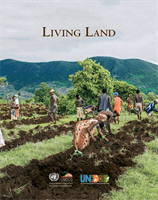

Cool season (April-October) mean sea level pressure near southern Australia showing an increase since 1950

Source: Pressure observations taken from National Centers for Environmental Prediction/National Center for Atmospheric Research reanalyses

Southern Australian Pressure (hPa)

1950

1015

1016

1017

1018

1019

1020

1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980

1985

1990 1995 2000 2005 2010

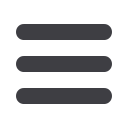

A dry lake bed (Tchum Lake) in the Mallee region of Victoria at the peak of the

hydrological drought

Image: Australian Bureau of Meteorology

L

iving

L

and