[

] 153

guide to the future, and the very real fears for water supplies in

the event that the drought continued.

The distinctive feature of abnormally heavy warm season rain-

fall in the north and cool season rainfall deficits in the south

has no obvious parallel in the historical record, and is not easily

understood in terms of the dominant natural variability tied to

the El Niño Southern Oscillation. Past droughts tended to extend

across most of Australia and have a particular focus across the

eastern third of the country, where rainfall is reduced during El

Niño events. The millennium drought, however, manifests out

of strong seasonal rainfall across Australia, which also provides

insight into the proximate (‘local’) cause of the drought.

Rainfall in northern Australia is dominated by the summer

monsoon, with rain coming from storms, monsoonal lows and

the occasional tropical cyclone between November and April.

The cool season is virtually rain-free with high rates of evapo-

ration, low humidity and clear skies.

In southern Australian (south of about 35°S), most of the

annual total rainfall comes as a result of cold fronts and mid-

latitude (baroclinic) low pressure systems. These systems peak

between April and October (the cool season) when the lows

in the Southern Ocean tend to move closer to Australia as

the dominant belt of high pressure moves further north to be

placed over the Australian landmass. While summer rainfall

does occur, surface water balance is such that during the warm

months it contributes very little to water supplies for urban use,

and has very limited use for agricultural production.

Southern Australia sits on the northern limit of the mid-

latitude westerlies and is particularly susceptible to shifts in

the intensity and latitude of fronts, low and highs. Of particu-

lar importance is the dominant high pressure belt, known as

the Subtropical Ridge, which extends across central Australia

during the cool season. This high pressure belt is the cause of

the semi-arid and arid dry zones that occupy the subtropics

in both the northern and southern hemispheres. A poleward

shift in the high pressure belt and increases in its intensity

means dry zones expand further into the mid latitudes (and

vice versa). El Niño events are one factor that can drive an

expansion and intensification of the high pressure belt over

Australia, which is part of the reason for the droughts that

Australia commonly experiences during these events.

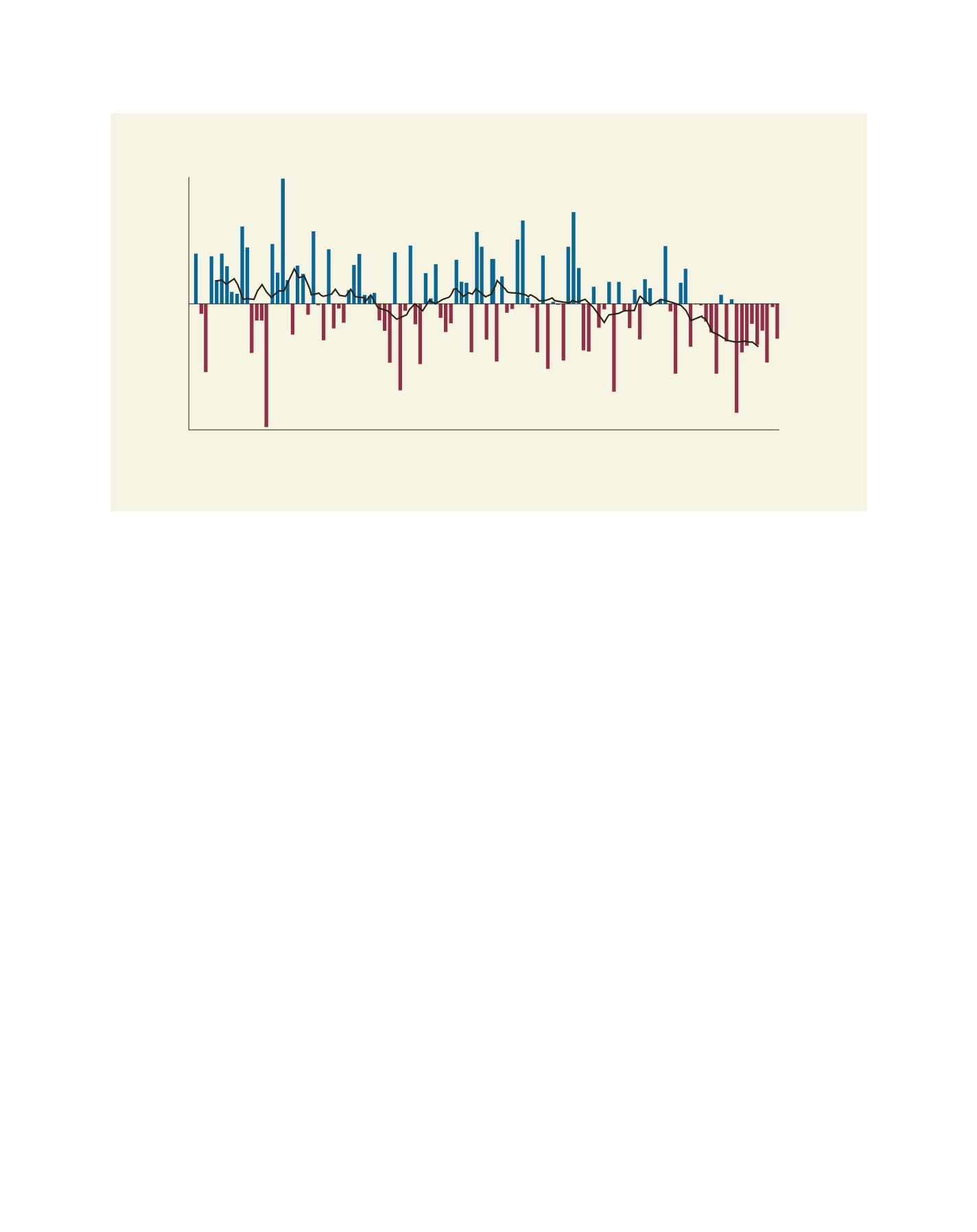

The April to October cool season rainfall across southern

Australia shows a systematic decline in recent decades that

is broadly consistent with climate change projections for the

region. The recent multi-year drought appears as a continu-

ation of lower rainfall which commenced in the 1970s. The

initial decline appears as a loss of very wet years and more

recently the near-complete dominance of below-average rain-

fall conditions year after year. During the past decade the mean

rainfall in this region is more than 15 per cent below average,

meaning the loss of more than 1.5 years of cool season rainfall

in total during the millennium drought. This anomaly is more

than twice as large as for any previous like period and up to

four times as large in some high rainfall catchments relevant

to urban water harvesting in southern Australia.

The recent decline in rainfall has coincided with increasing

atmospheric pressures between the months of April to October

and a subsequent decline in the penetration of fronts and lows

across southern Australia. The intensifying pressure means an

increasing dominance of dry weather as the subtropical ridge

has become more dominant. Atmospheric pressure across

Australia shows remarkably strong correlations with rainfall

and explains some 60 per cent of the year-to-year variability

(variance). The accumulated impact of the trend in pressure

implies a mean rainfall reduction of nearly 50 mm over the past

50 years. This figure is close to the anomalies which have been

observed during the millennium drought in southern Australia.

In other words, the proximate cause of the recent cool season

Cool season rainfall in south coastal Australia: the solid line shows the 10-year running anomaly

Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology

Year

1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

200

150

100

50

0

-50

-100

-150

-200

Rainfall Anomaly (mm)

L

iving

L

and