[

] 151

is very windy we put broken, spikey branches from the Balanites

aegyptica tree on top to make sure the materials will not fly away.

Two weeks later, parents have planted the posts for the iron

mesh protection and dug the rest of the trenches. I put my

hand into the mixture, take a handful of the already fermenting

compost and sniff it. This shocks the children and parents at first,

but they don’t see the different components anymore, only the

black compost, and once everybody has sniffed it they agree that

it does not smell bad. In fact, there is always a child who says that

it “smells like the rainy season”, like earth after the first rainfall

— and that is a delicious smell to all Sahelian noses.

I then start putting aside the straw layer with the help of

Appolinaire Bazié or Souleymane Diabaté. We ask pupils to bring

water and we pour five watering cans full in the second trench.

We start throwing the contents of the first trench into the second,

and after three minutes the picks and shovels are taken from our

hands and parents, teachers and pupils take turns (temperatures

are 35-45 degrees Celsius depending on the season). For the first

turnover you need only the first five watering cans of water at the

bottom and five on the top layer before you put the straw cover

on it. Then we fill the first trench again, as we did before.

We bring a dozen young trees for this visit, and we give a tree

planting course: dig a hole 60 cm deep and 40 cm in diameter,

throw in about five litres of water tomake a water reserve, mix one

third of young compost with sand or small gravel and red earth.

Undo the recycled plastic bag with care, free the roots, place seed-

ling in the half-filled hole, fill and harden the soil with your fist to

make a small basin and complete withmulching and protection—

this can be a nicely woven basket or amakeshift jobwith branches.

The rest of the trees will be planted by the teachers.

Six weeks after the first practice we return to find three trenches

underway, and two- and four-week-old compost. Pupils have

hewn and watered the future vegetables beds. This time we bring

more young trees, seeds and vegetable seedlings that are 20-30

days old. Pupils plant a mix of vegetables of different families (it is

a challenge to explain that tomatoes, aubergines and potatoes are

of the same family and so ‘eat’ the same nutrients in the ground)

and then mulch with a mixture of chaff, dried leaves and grass,

watering every evening the first week and three times a week —

or even twice weekly — during the next weeks. This is judged by

digging a forefinger in the soil: if the soil is ‘cool’, don’t water. In

two to four weeks cooks will have something to use, pupils will

have seen different stages of vegetable development and learned

that some will perhaps not give anything, in spite of loving care.

Semi-ripe compost can be used with different vegetables. Pierre

Rabhi, the inventor of that technique, kindly allowed us to copy

the drawings in his book and leave them in the schools.

Finally, in week eight the compost is ripe: it can be used

for cereals or dried in the shade and put in sacks for further

use, especially during the rainy season when too much water

would make it rot and smell. In the meantime the ‘compost

wheel’ continues to turn. There is always something underway

and the schools produce 500 kg of compost every two weeks

after the first two months. This amount can improve a half-

hectare in cereals or vegetables, so we ask the schools to share

it with the parents who help out.

That’s how schools in several villages have each planted

a garden and trees, and how every year four or five parents

in each village have tried for themselves. It is the way many

women’s groups have learned how to grow vegetables without

buying fertilizers and how to protect against predators with

azadirachta indica oil or tea, tomato leaves or dangling broken

CDs against the birds, how to make paper balls for the stove

instead of burning it away, and how to use old plastic bottles

for insect traps or slow-drip watering.

Each successive DPENA has facilitated our work, understand-

ing the long-term issues. Our dream is to make it part of the

primary schools curriculum in Burkina Faso so that in every dry

yard, even in town, on every dry patch of land, everyone will have

the know-how to grow vegetables, beans, cereals and trees, with

three times more than the average chemically fertilized produc-

tion, with little water, less hard work, no chemical pesticides,

little expense and a nice profit. Sahel will be green again, forests

and rains will come back, and hunger will be a ghost of the past.

1

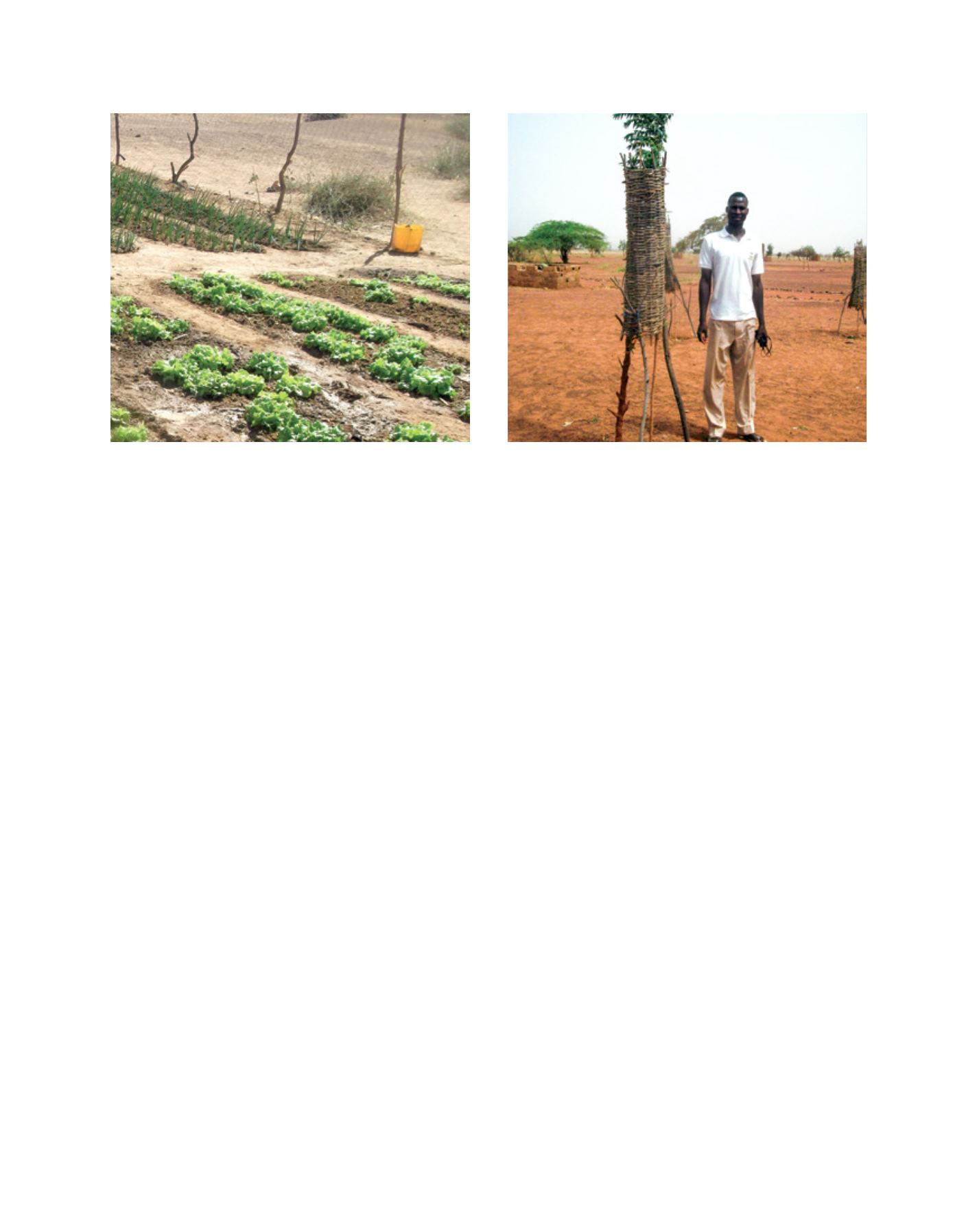

A mix of vegetables and plants in the hewn and watered beds

Young trees are protected by woven baskets

Image: Association Pour un autre monde

Image: Association Pour un autre monde

L

iving

L

and