[

] 103

H

ealth

Data for the central (including Central, Guadalcanal,

Isobel and Honiara provinces) and western (including

Western and Choiseul provinces) regions were aggre-

gated, while the provinces of Makir, Temotu and Malaita

were treated as separate regions. The grouping of data in

this way gave significant consideration to geographical

location, orographic effects and the availability of malaria

outpatients and climate data. Considerable adjustments

were made to population data and the associated records

on malaria incidence to reflect the groupings, and the

malarial incidence was calculated as a Positive Incidence

Ratio (PIR), which is defined as the number of positive

films per 1,000 head of population.

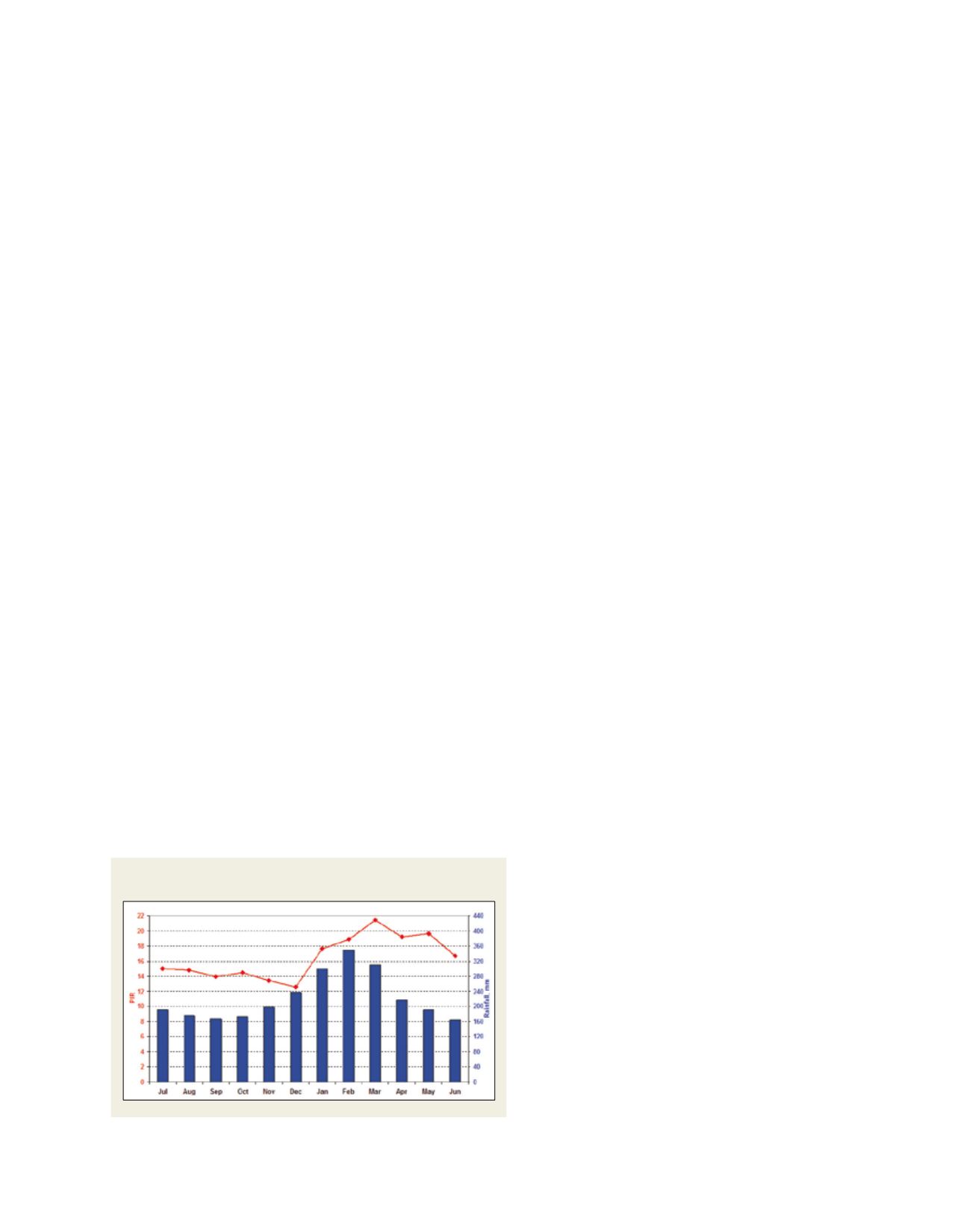

The numbers of confirmed malaria cases were iden-

tified using data from 1975-2008 during the peak

infection period (December to May). Linear and

non-linear regression techniques were used to relate

PIR to climate (temperature and rainfall) and non-

climate (for example, population growth) factors.

The analyses show that incidence of malaria peaks

during the wet season (December to April). However,

it was also evident that, somewhat counter-intuitively,

above median rainfall during this peak period tends

to suppress the number of malaria cases. The likely

cause is a flushing out of mosquito breeding sites by

the heavier than normal rainfall. Conversely, below-

median rainfall during the wet season tends to increase

the incidence of malaria.

Together these results indicate that malaria would

tend to be more prevalent during El Niño events and

less so during La Niña events. The maximum correla-

tion between rainfall and PIR is subject to a significant

lag time, with PIR lagging rainfall by approximately

two months. This makes rainfall a useful param-

eter for forecasting PIR with sufficient lead time to

inform planning and management decisions. On the

other hand, temperature influence on the number

of malaria cases tends to have a shorter lag period,

hence lower than normal rainfall from November to

January followed by higher than normal temperatures

in December and January triggers a high incidence of

malaria in the Solomon Islands.

Health data collected from SIMTRI showed that the

PIR was relatively high from 1990 through to 1995,

at a time when El Niño patterns prevailed from April

1991 to March 1995. Five out of six November-April

rainfall totals were below average during this period.

Climate factors (rainfall and temperature) explained

up to 70 per cent of variability in the number of

malaria cases. An early warning system for malaria

based on seasonal climate forecasts for the peak infec-

tion period was therefore assessed to be viable for the

Solomon Islands.

It is also noteworthy that projections of future climate

suggest an increasing trend toward higher temperatures

and no significant change in the rainfall pattern for the

Solomon Islands, which could pose a future increased

risk of malaria and therefore an increased urgency for

the development of improved management strategies.

Tackling malaria

Malaria is a primary focus of one of the United Nations Development

Programme (UNDP) Millennium Development Goals

2

and remains

one of the most widespread and devastating infectious diseases in

tropical developing countries around the world.

The Solomon Islands is no exception, where malaria is a leading

cause of death. World Health Organization data published in April

2011 showed a malarial death rate of approximately eight per cent

of total deaths. The age-adjusted death rate of approximately 30 per

100,000 of population ranks the Solomon Islands as 33rd in the

world. Malaria continues to have a high cost in both economic and

social terms in the Solomon Islands, with low productivity at work

and absenteeism in schools.

In the Solomon Islands,

Plasmodium falciparum,

the severe and life-

threatening form of malaria parasite, accounts for 60-70 per cent of

all confirmed cases. As mosquitoes are the carrier of this disease,

worldwide malarial epidemics tend to occur when environmental

conditions such as rainfall, temperature and relative humidity create

optimal conditions for mosquito breeding.

The climate of the Solomon Islands is significantly influenced by

the ENSO phenomenon. El Niño conditions are generally associated

with below-average rainfall and above-average temperatures, while

La Niña conditions are generally associated with above-average rain-

fall and below-average temperatures. The tendency for an ENSO

state to develop and persist once it is initiated makes it possible

to forecast seasonal rainfall and other hydroclimatic variables with

some accuracy, employing key climate indices such as the Southern

Oscillation Index and patterns of Sea Surface Temperature anom-

alies. Therefore there is potential to forecast the elevated risk of

malaria outbreaks in the Solomon Islands with sufficient lead time

to reduce the potential incidence of the disease through targeted

control strategies.

Lessons from data

In collaboration with SIMTRI, records of both confirmed and

suspected (unconfirmed) malaria cases for nine provinces were

obtained for the period 1975-2007. Corresponding climate data for

this period, including rainfall, maximum and minimum temperature

and relative humidity data, were prepared by SIMS.

Records were collected for each of the nine Solomon Island prov-

inces and were collated into five regions for the purpose of this study.

Average monthly PIR and rainfall for the Solomon Islands,

1975-2007

Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology