[

] 162

O

bserving

, P

redicting

and

P

rOjecting

c

limate

c

OnditiOns

to constituents, build political support for appropriatemeas-

ures, and defend approved legislation against legal challenge.

Rather than pointing towards sweeping conclusions as

to whether projections are adequate, the CCCI’s initial

experience in pilot cities is yielding a more nuanced

answer. First, projections regarding GHG emissions are

adequate for planning mitigation measures. Projections

have been of a sufficient degree of confidence to jolt

the international community into setting up carbon

finance mechanisms – these can finance projects that

will contribute to net reductions. The desire to imple-

ment such projects is likely to be the immediate driver

for cash-strapped cities with regards to mitigation,

and current climate projections are adequate for that

purpose.

7

A number of cities have calculated baseline

GHG emissions and committed themselves to reduc-

tions at the city, project or building level.

8

No further

refinements of global or regional models are required to

take such actions. Unfortunately, however, it is adapta-

tion and not mitigation that is the pressing concern, and

here the record is more uneven.

ranges.

4

Residents of CCCI cities face a gamut of climate-related

stresses and risks:

• Kampala (population 1,654,000) – an inland city, is the capital

of Uganda. An estimated 45 per cent of residents live in low-

lying areas at risk of flooding

• Maputo (population 1,094,000) – is the capital of Mozambique.

In 2000, cyclones and torrential rains inundated this coastal city,

killing 700 people and wreaking USD600 million in property

damage. In recent years the region has also suffered from drought

• Esmeraldas (population 195,000) – is a coastal city in Ecuador.

Planners estimate that almost 60 per cent of the population lives

at medium-to-high risk of flooding or landslides

• Sorsogon City (population 151,000) – lies at the southern tip of

Luzon, the largest island in the Philippine archipelago. Cyclones have

buffeted this coastal city in recent years. In 2006 Typhoon Milenyo

affected around 27,000 families and severely damaged 10,000 houses.

Climate change is likely to further impact these cities in the coming

decades. CCCI teams are helping local stakeholders to assess impacts

and vulnerabilities, and devise adaptation and mitigation strategies

and demonstration projects. As of July 2009, all four are still in an

early stage of assessment. The teams begin by assembling histori-

cal data regarding flooding and landslides, then review available

projections, including those found in the Contribution of Working

Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) prepared by the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Teams addi-

tionally gather available regional or national projections. CCCI teams

are in the process of overlaying that data upon local-level geograph-

ically-referenced information regarding land use, populations and

infrastructure, to preliminarily gauge vulnerabilities. This technical

analysis occurs alongside, and informs, consultations with stakehold-

ers – this process will lead to strategic plans for priority actions.

Applicability of urban management tools to

climate change phenomena

Officials can use different types of urban management tools to

address various climatological phenomena. Broad types of tools and

specific examples include:

• Planning – a general plan that guides a city’s long-term growth

• More specific development regulations – a zoning ordinance

that defines what types of land use can occur

• Property acquisition – a decision to purchase undeveloped lands

due to a public interest

• Public infrastructure and facilities – a resolution regarding the

siting of a water treatment plant

• Building standards – a code that promotes energy efficiency.

5

These tools have different applications in relation to impacts.

Building codes can address increases in mean temperature, zoning

regulations can respond to sea-level rise (SLR), and so on. A much

more robust suite of tools exists for addressing certain types of

phenomena (such as storm surge) than others (such as heat waves).

6

Findings regarding the use of climate change projections

for urban management

Climate change projections must be sufficiently precise, and of a suffi-

cient level of confidence, that officials can apply an appropriate urban

management tool to effectively address the impact in question. Meeting

this threshold of adequacymeans that officials will be able to explain risks

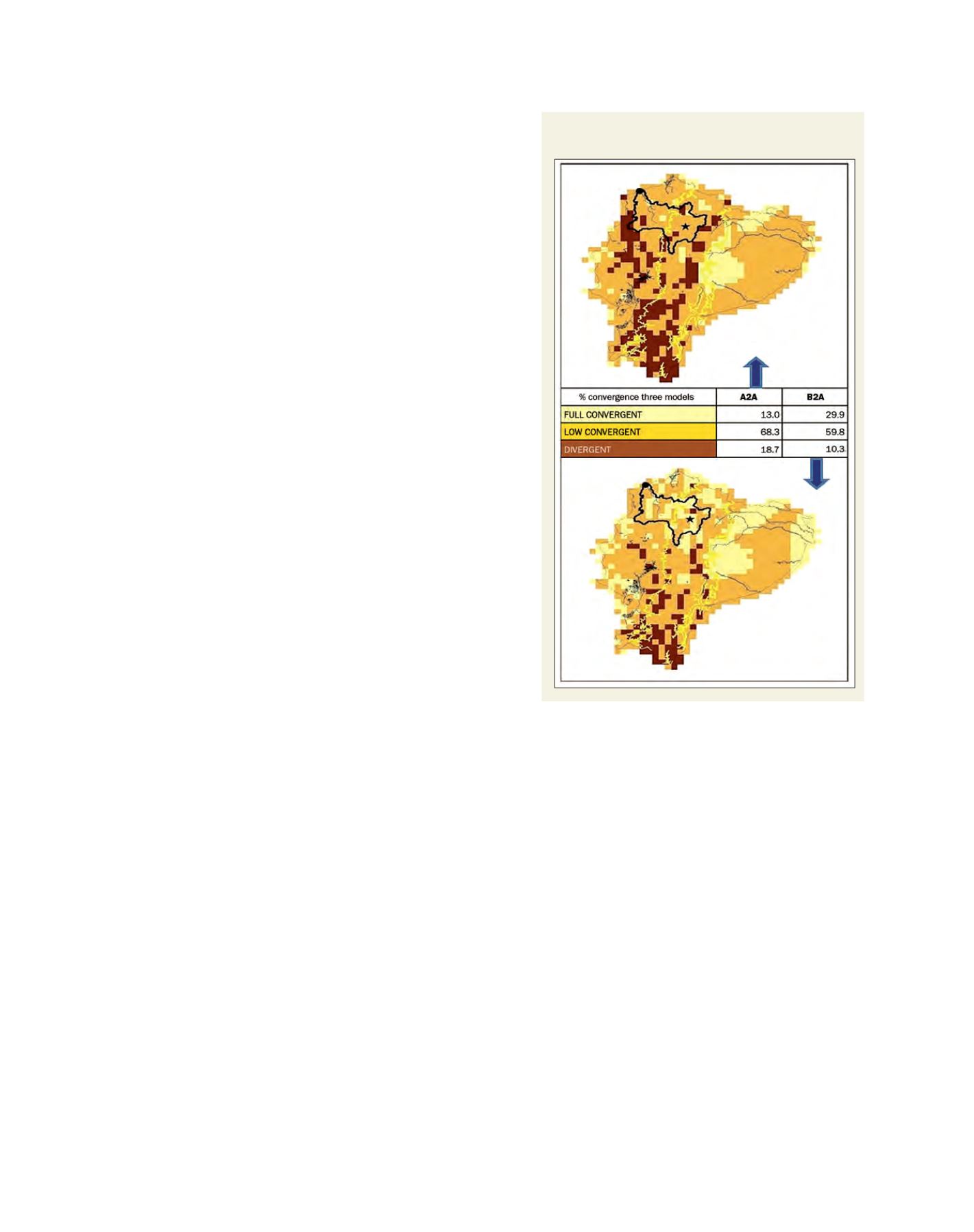

Comparison of three climate models under

two emissions scenarios in Ecuador

Source: UN-HABITAT, Climate change assessment for Esmeraldas,

Ecuador, 2009