[

] 33

T

he

I

mpacts

and

I

mplications

of

C

limate

C

hange

and

V

ariability

and better methods for quantifying uncertainties are all

required to provide useful information about the poten-

tial for, and impacts of, extreme events. It is important

to recognize, however, that aspects of uncertainty at

fine scales will remain irreducible.

Expand capacity to provide relevant climate information

to decision makers and the public

– Through interactions

between information providers and users, monitoring

systems, distribution networks, and information tools

can all be developed and refined. Monitoring efforts

need to adhere to principles that ensure the quality

of observations, and improved access to data archives

will facilitate society’s ability to respond to change.

Credible climate services must provide reliable, well

documented, and easily used information. While

implementation is most important at a national scale,

many decisions and policies addressing impacts take

place regionally. Experience has demonstrated that the

practice of climate services requires sustained, ongoing

regionally-based interactions with users.

Improve understanding of thresholds for abrupt climate

changes

– Climate has shifted regimes relatively quickly

in the past, suggesting it is capable of doing so again in

the future. More needs to be learned, however, about

the tipping points that can trigger such changes. The

sensitivity of major ice sheets to sustained warming is

of concern in this regard, requiring improved observa-

tions, analysis, and modelling of ice sheets and their

interactions with surrounding oceans. Thresholds in

biological systems also need to be better understood.

Improve understanding of most effective approaches to

mitigation

– Different paths to reducing concentrations

of greenhouse gases exist, and a mixture of mitigation

‘agenda for climate impacts science’ described in a state-of-knowl-

edge report entitled Global Climate Change Impacts in the United

States published by the US Global Change Research Program.

1

It

recognizes that advances in scientific understanding have already

contributed greatly to decision making. Further advances are

required, however, to better understand and project changes in rain-

fall, storm tracks, storm intensity, heat waves, and sea-level rise.

With respect to advancing knowledge specifically about the impacts

of climate variability and change and the processes responsible,

the report makes six recommendations that would better ensure

the information provided by climate services is of use to decision

makers:

Expand understanding of climate impacts

– Increased knowledge

is needed about how ecosystems, economic systems, human health,

and the built environment will be affected by climate variability and

change in the context of multiple stresses. This will be derived from

sustained observations, field experiments, model development, and

integrated impact assessments performed through collaborations

among researchers, practitioners and stakeholders.

Refine the ability to project climate variability and change at local

scales

– Decisions on adaptation will be made largely at local and

regional scales. Although progress is being made at these scales,

significant uncertainties remain. Higher resolution models, improved

downscaling approaches, additional observations at relevant scales,

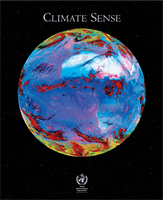

Arctic sea ice annual minimum

Arctic sea ice reaches its annual minimum in September. The satellite images show

September Arctic sea ice in 1979, the first year these data were available, and 2007

Source:

Sea Ice Yearly Minimum 1979-2007

, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

Scientific Visualization Studio (GSFC)

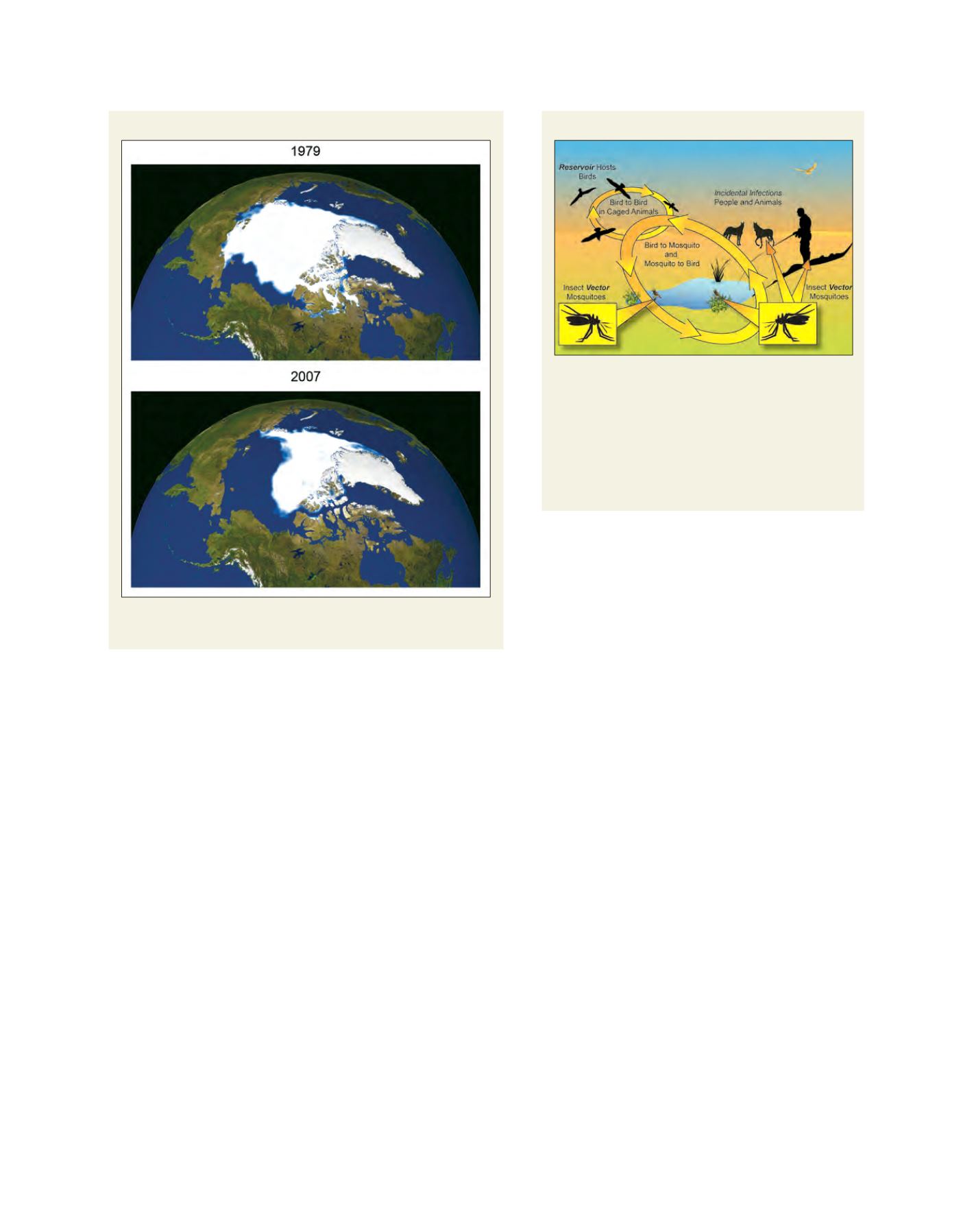

West Nile virus transmission cycle

While migratory birds were the primary mode of the West Nile virus

spread in the United States after the first outbreak occurred in 1999,

epicentres of the disease were linked to locations with either drought

or above average temperatures during the epidemic summers of

2002-2004. Analyses of a more virulent strain that emerged in

2002 indicate this strain responds strongly to higher temperatures,

suggesting that greater risks from the disease may result from

increases in the frequency of heat waves

Source: Karl et al. (2009)