[

] 117

T

RADITIONALLY LIVESTOCK WAS

a unique source for sustain-

able living in a country with an extreme climate and

insufficient and irregular distribution of both heat and

moisture. Here, the cold weather lasts for six to eight months and

the natural grass growing season is short; it lasts for a mere four

to five months. More than 80 per cent of atmospheric precipita-

tion falls by the end of the growing season.

In such an unstable environment the ecosystem is poor, and

pastoral animal husbandry is a factory that operates all year round

and produces living necessities. Here, nature and herders are “co-

investors”. Nature invests for grasslands and the herder invests for

his livestock. Approximately 50–1 200 kg/hectares of annual

grass growth, coupled with the herders’ labours, provides one-

third of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and a quarter of the

country’s export sales.

Global change affects Mongolia, causing temperatures to rise

twice as rapidly as the global average. The epicentre of atmos-

pheric pressure changes is located in Mongolia. The faster the

climate changes, the greater the risk of disaster. Steppe grasslands

are considered particularly vulnerable to such changes, so pastoral

animal husbandry, which is wholly based on weather and natural

grasslands, is at great risk.

A severe drought, a dzud disaster and an epidemic disease

affected the livestock sector during 1999–2003, and as a result,

How to reach the rural herders

scattered across Mongolia

R.Oyun, Coordinator, Risk Study Working Group and Director,

JEMR Consulting Company, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

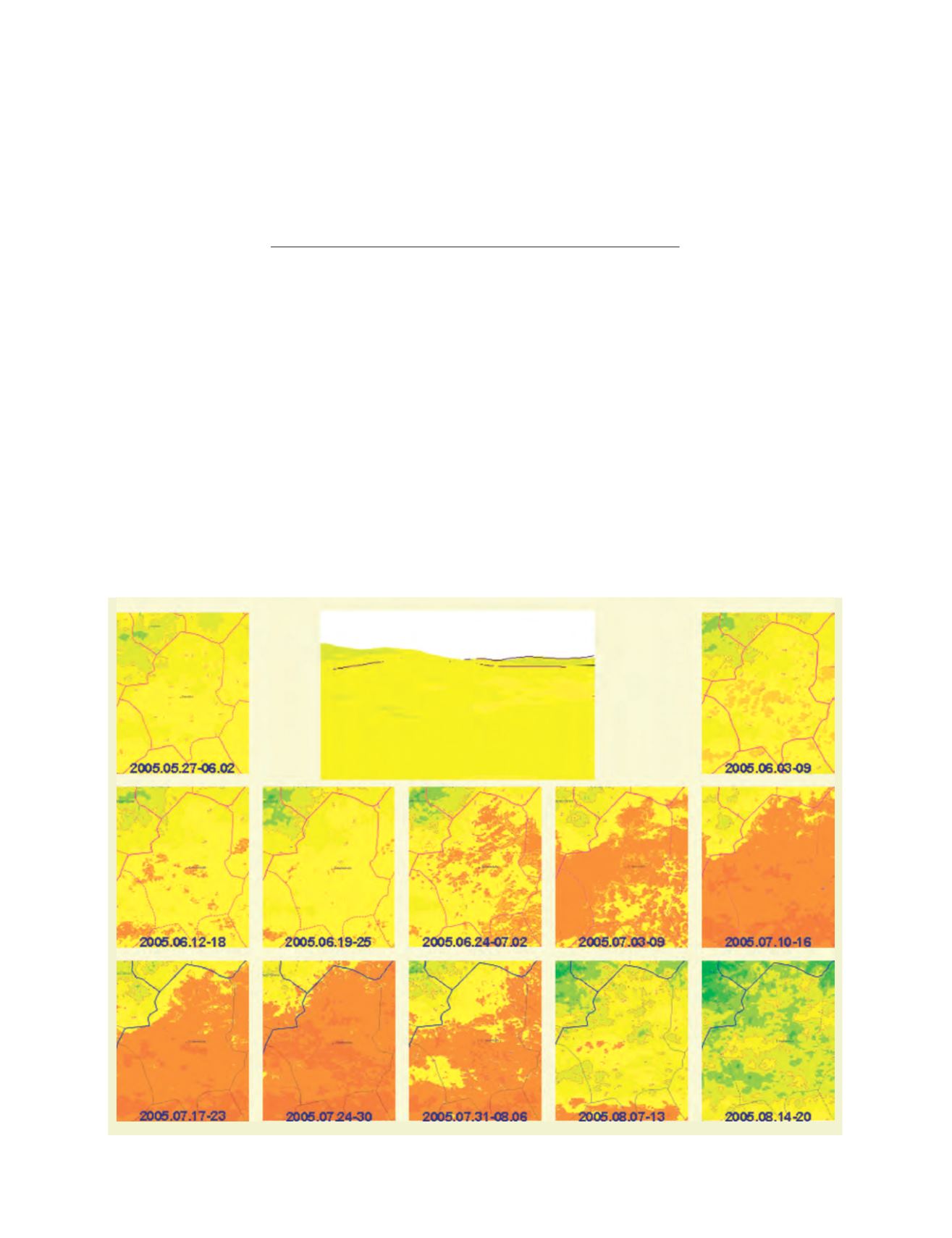

Figure 1: Weekly monitoring of pasture vegetation and its biomass for Erdenedalai county with use of ground and NOAA AVHRR data