Such an approach is new in Mongolia and important to ground-

level government policy, development strategies, governance and

business operation down to the rank of the households – a

primary unit of the society – and peoples’ livelihoods. Linking

a household with its surrounding natural and artificial environ-

ment will lead to an accountable relation between the head of a

family and public and private stakeholders.

Satellite remote sensing is a valuable information source, and

geographical information systems (GIS) embody a useful tech-

nology for working with digital maps. But they are not affordable

for the small county economies. Moreover, their technology is not

accessible to the public as it is very expensive and requires appro-

priate capacity building. In addition, transmitting and

downloading a large volume of digital images requires a high-

speed data network.

Database contents of the above mentioned two counties have

some specifics in complexity due to differences in climate, natural

environment, economic systems and administrative and territo-

rial units. The economy in Erdenedalai is based solely on the

livestock sector, while Mandal has forest areas, livestock, crop

and vegetation farms, mining, wood, urban and rural areas, a

well-developed infrastructure with paved and railroads. Therefore

the digital content of Mandal is more complex than the

Erdenedalai. The majority of Erdenedalai’s population are herders

who migrate with their animals, while the majority of Mandal’s

population are settled urban citizens and farmers.

Digital information flow is the lifeblood for making e-Soum

work. Technology provides tools to foster a well-integrated infor-

mation flow to the right people at the right time. In addition,

digital processes monitor, assess, predict and manage any

phenomenon and changes of a system and its environment, and

react appropriately to their impacts.

An example of digital information flow can be seen from the

risk manager system established at the Erdenedalai. It has three

directional data flows and provides coordinated action on the

information of 15 organizations (Figure 2). Top-down data

consists of daily, weekly and monthly weather predictions down-

scaled to and specified by different areas of the county territory,

warning messages for hazardous phenomenon, weekly maps of

pasture vegetation and temperature produced by using advanced

technology such as remote sensing and GIS. Bottom-up flow

provides informal data from the herders and farmers on air pres-

sure, temperature (measured by general equipment), extreme

meteorological phenomena that affect people and livestock,

households, and some data from county meteorological stations

and local government that is necessary for vulnerability studies

and risk assessment. Horizontal information flow helps to coor-

dinate the activities of different stakeholders in the county, namely

local government officers responsible for social insurance, agri-

culture, land and disaster management, bahg governors, the

county hospital, veterinary procedures, the meteorological station

and local FM radio.

Pilot projects that started in May 2005 to assist crop farmers

from the Tsagaannuur and Tushig counties in the province of

Selenge and in the Teshig county of the Bulgan province are to

provide more detailed information on weekly and long-term

[

] 120

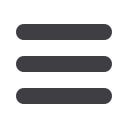

Figure 3: Spatial database for Tsagaannuur county

Land cover/use

Vegetation

Soil moisture

Temperature