[

] 260

Securing Australia’s groundwater future

Professor Craig T. Simmons, Director, National Centre for Groundwater Research and Training, Australia;

and Neil Power, Director, State Research Coordination, Goyder Institute for Water Research, South Australia

T

o many outsiders Australia is a land of surf and sun-

drenched beaches. But venture a short way inland and it

is mostly semi-arid and desert, a land mass where drought

is all too common and water is an extremely valuable commodity.

To prosper in such a parched and unforgiving environment, the

nation has become increasingly reliant on groundwater. From a

largely untapped resource 40 years ago, groundwater is now the life-

blood of communities and key to economic development for large

parts of the country. An estimate widely accepted by scientists and

policymakers is that groundwater now directly supplies more than

30 per cent of the nation’s consumptive use.

Access to such low-cost, good quality water has delivered massive

social and economic benefits, allowing industry and urban and

regional centres to flourish. Without it, agriculture and mining

would struggle, numerous rural towns and cities such as Perth,

Newcastle and Alice Springs would lose their main water source,

and countless dependent ecosystems would perish.

Managing the impact of this rapid increase in extraction and

securing the long-term future of the resource for all users is

highly complex and challenging. It involves many

competing interests – community, industrial and

environmental – as well as federal, state and local

levels of government.

One of the biggest challenges is to manage the

cumulative environmental impact of multiple actions

on the baseflow of rivers, springs, wetlands and other

groundwater-dependent ecosystems. The uncertainty of

climate change and climate variability is adding another

layer of complexity. The concern is that if groundwa-

ter is not properly managed, over-development could

result in the irreversible degradation of aquifers and

affect the reliability of surface water resources. Such a

scenario would have significant economic and environ-

mental ramifications.

Efforts to better understand and manage groundwa-

ter have been the subject of various intergovernmental

initiatives over the past 20 years. These have increasingly

focused on the need for a coordinated, national response.

The most recent initiative – the National Groundwater

Action Plan, which was funded by the Australian

Government through the National Water Commission

– helped explore knowledge gaps through extensive

hydrogeological investigations and assisted in establish-

ing the National Centre for Groundwater Research and

Training (NCGRT) for large-scale capacity building.

While good progress is being made, there is recogni-

tion that Australia still has some way to go to secure

its groundwater future. Recent projects have succeeded

in developing general tools, baseline assessments and

guidelines to improve groundwater management, but

the work started from a relatively low base.

Australia still needs to answer critical questions in

areas such as the scale of groundwater use and its deple-

tion, the impacts on connected surface water resources

and the risk of increased salinity posed by high levels

of extraction. Accurately quantifying total groundwater

use is just one side of the ledger; estimating recharge

is even more challenging. The recharge process can

be extremely long-term, sometimes stretching over

hundreds of thousands of years.

To achieve long-term goals, a new National

Groundwater Strategic Plan is being developed to guide

policy and decision makers over the next 10 years. The

planning process is groundbreaking in that it has sought

input from all key stakeholders, including water manag-

ers, policymakers and researchers across national, state

E

conomic

D

evelopment

and

W

ater

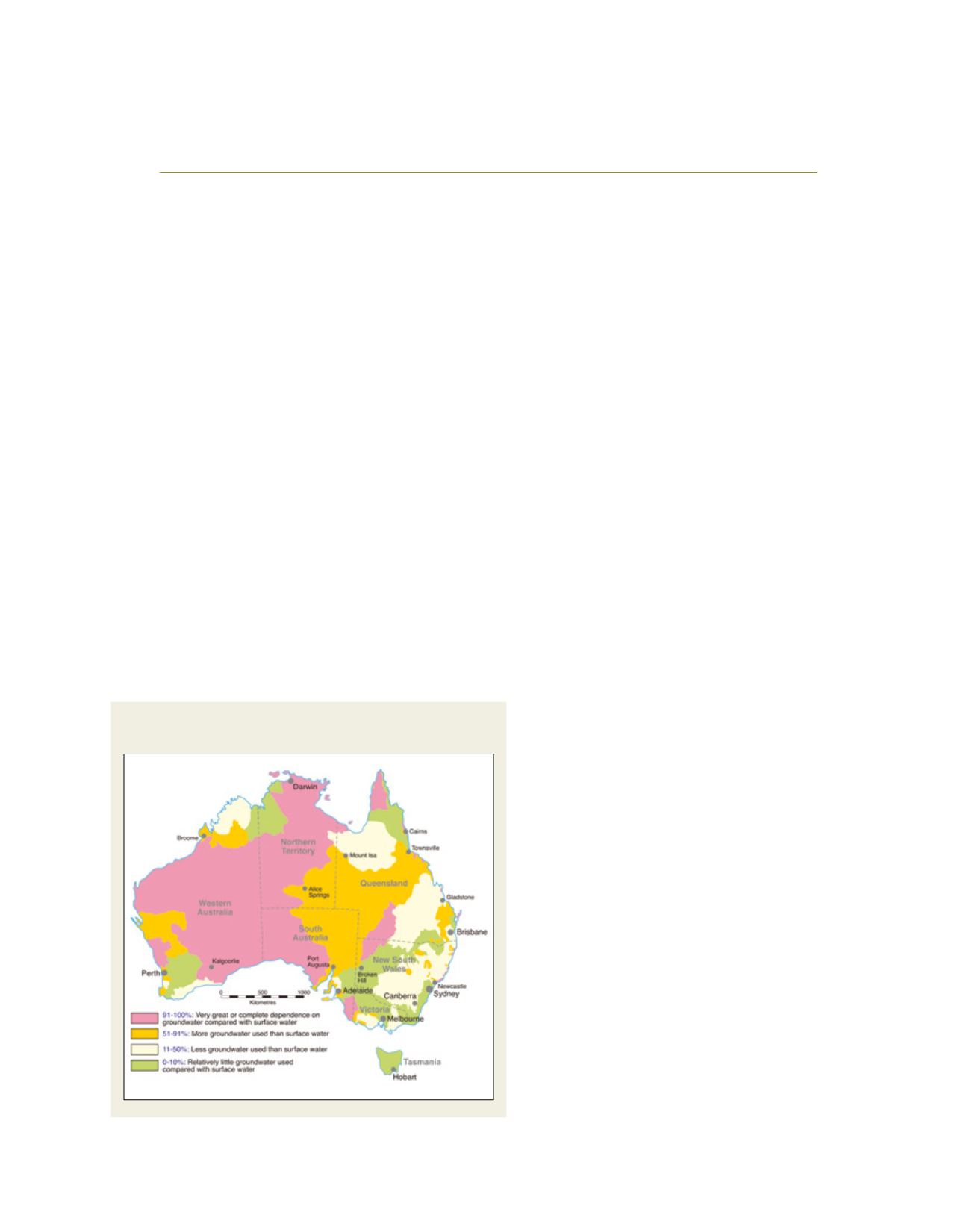

Groundwater use in Australia as a percentage of total water use in

key catchments across the country

Source: Australian Water Resources Council/CSIRO