[

] 257

E

conomic

D

evelopment

and

W

ater

tion (about two thirds of the demand), but also in the

Olkaria Geothermal Power Station, which generates

around 15 per cent of Kenya’s power and is the largest

single user of lake water.

It was widely believed that the lake was over-abstracted

because by the middle of the first decade of this century,

there was no overall monitoring of abstractions –

although the major commercial abstractions, being

important sources of revenue for the Water Resource

Management Authority (WRMA), were subject to scru-

tiny. While the Government of Kenya had created a

National Environmental Management Authority under the

1999 Environmental Management and Coordination Act,

and theWRMA through the 2002Water Act, enforcement

of regulations proved to be weak. Fuelled by media arti-

cles in Kenya and the UK, conservation agencies and the

public perceived two growing threats to the lake and its

biodiversity: human population growth leading to physical

pressure on the shores, and untreated wastewater flowing

into the lake from industries and settlements.

The Lake Naivasha Riparian Association (LNRA), the

group representing lakeside landowners, had produced a

Management Plan, which formed the basis of the decla-

ration of the site as a Ramsar Wetland of International

Importance, in 1995. This Plan was approved by the

Kenyan Government and officially gazetted in 2004

under the 1999 Environment Act, resulting in the forma-

tion of a dedicated management committee. However,

many people (including pastoralists, smallholder farmers

and residents of Naivasha’s informal settlements), whose

livelihoods depend on the ecosystem services of the lake,

were excluded from the consultation process and from

representation on the committee. A temporary coalition

of pastoralists lodged a successful court injunction against

America, arrived in 1988. It thrived because it had no competition from

native plants, particularly the Blue Water Lily that had disappeared.

The nature of agriculture around the lake began to change after

1975. By 1995, small farms had given way to several square kilo-

metres of irrigated horticulture in large units, with output (flowers

and vegetables) air-freighted to Europe. The cultivated area had

doubled by the start of the twenty-first century, and this land use

change brought a tenfold rise in the population of horticultural

estate workers and their dependents, to 250,000.

The most significant impact of this growing agricultural inten-

sification was the abstraction of water from the lake, groundwater

and rivers. No doubt, smallholder use of water higher in the catch-

ment also increased, but this was ‘invisible’ to journalists and other

visitors. Scientific studies in the 1990s showed the abstractions

from the catchment to result in fluctuations of the lake 2-3 metres

below its natural levels. The most visible and ecologically damaging

consequence of this was the disappearance of the fringing papyrus

around the lake. Stranded on dry land, large animals like buffalo and

cattle were able to knock down the plants’ heads and eat them. The

tracks they made enabled smaller animals to follow and graze any

regrowth, so the swamps were progressively eliminated.

The loss of the fringing swamps meant that the incoming rivers,

heavy with sediment from inappropriate farming upstream,

discharged their load directly into the lake instead turning it into

new swamp plant growth which would release nutrients slowly. It

became clear that the lake – browner in colour, with floating mats

of exotic plants and an edge no longer protected by papyrus – was

in urgent need of careful management and restoration.

Stumbling conservation initiatives

As the century drew to a close, the most important issue for Naivasha

was the increasing water use by the rapidly-growing industry of

commercial flower and vegetable farming for export. Demand for

fresh water was intense, not only for intensive horticultural irriga-

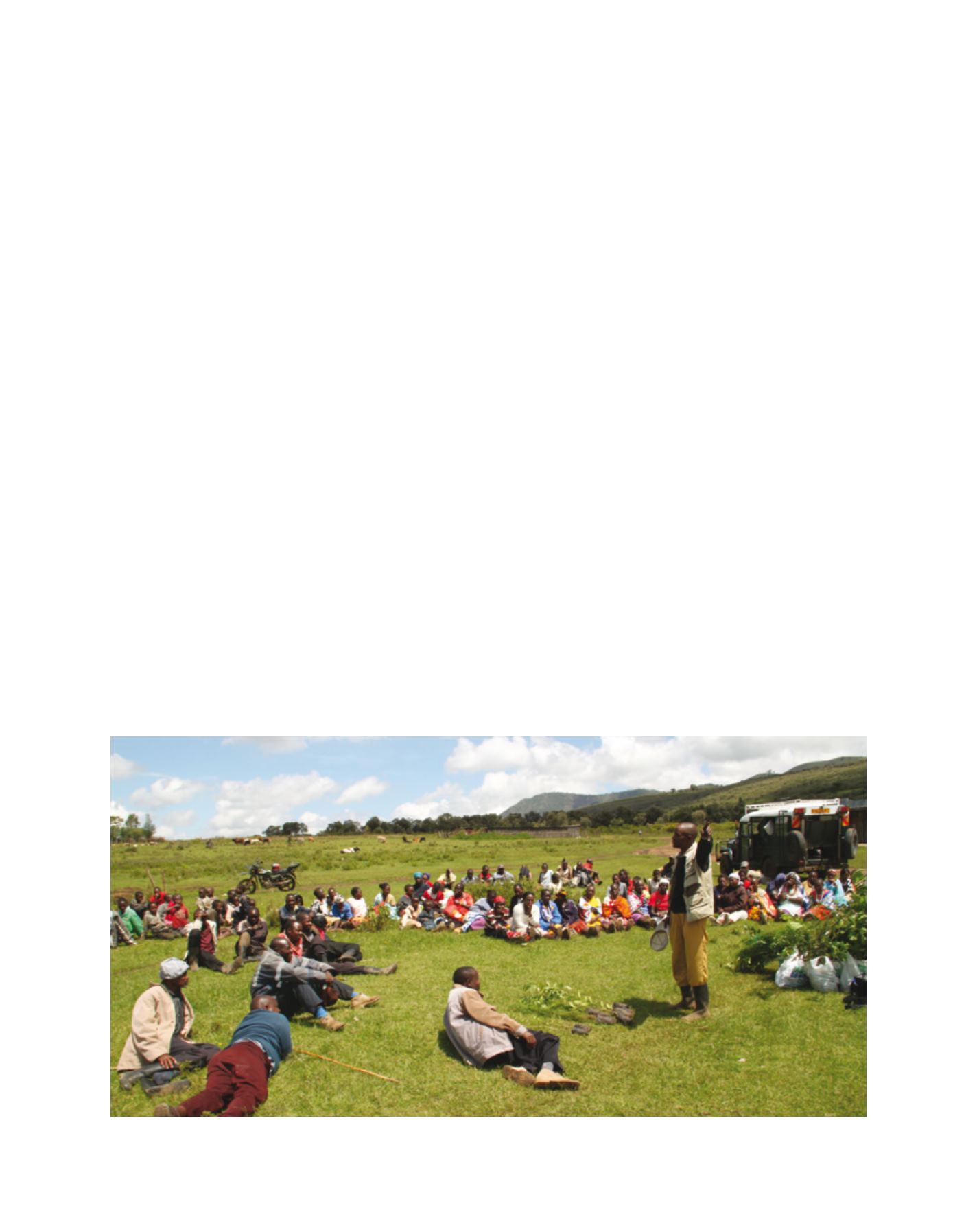

Distributing trees to farmers, who are encouraged to grow trees and terrace their land to arrest erosion

Image:Nic Pacini