[

] 254

W

ater

C

ooperation

, S

ustainability

and

P

overty

E

radication

director of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO) division of water sciences, I designed

the concept of an international and interactive electronic network

open both to water and anthropology professionals. The result-

ing Network of Water Anthropology (NETWA) was endorsed in

June 2002 by the 6th Programme of the International Hydrological

Programme to fit into its proposed new paradigm and themes.

The paradigm was based on the integration of culture, in its broad

meaning, in water sciences and their practical applications, with

themes including Water and Society; Water, Civilization and Ethics;

Water Education and Building Local Capacities; and particularly

Institutional Development and Creation of Networks for Water

Education and Training. I presented the framework during the

third World Water Forum in Kyoto in 2003, in the session titled

Translating the Cultural Dimension of Water into Action, and

during the fourth World Water Forum in Mexico, 2006, focused on

Local Actions for a Global Challenge.

2

When I was assigned to go to Mali as a UNESCO Senior Expert

consultant, working in the frame of World Heritage, Professor

Szollozi-Nagy thought it appropriate to root the NETWA project

in this Sahelian country. Mali is one of the poorest countries in the

world; it also faces the cruel impacts of climatic change, droughts and

floods affecting local people’s health and resources. A few decades ago,

the Niger river had made Mali the storehouse of West Africa for cereal,

fish, rice and meat, but today it barely feeds its own. Today, the river

is collapsing under the weight of human action and natural effects.

Riverside societies survive thanks to internal and external migration.

Those staying on its banks try to adapt to climate change through the

diversification of their activities (for example, choosing agriculture

over commerce). The Dean of the Faculty of Literature, Languages and

Social and Human Sciences at the University of Bamako,

Dr Salif Berthe, enthusiastically welcomed the NETWA

project

3

and mobilized human and material resources to

open a research centre on Water Anthropology as early

as February 2008, with the goal of promoting the cultural

practices of the Niger riverside societies.

4

In some places, the explosive growth of main water

and sewage systems designed by some international

cooperation projects has not improved local commu-

nities’ health and well-being. Mali is a region where

more than three quarters of the population live below

the poverty line and literacy and healthcare indices are

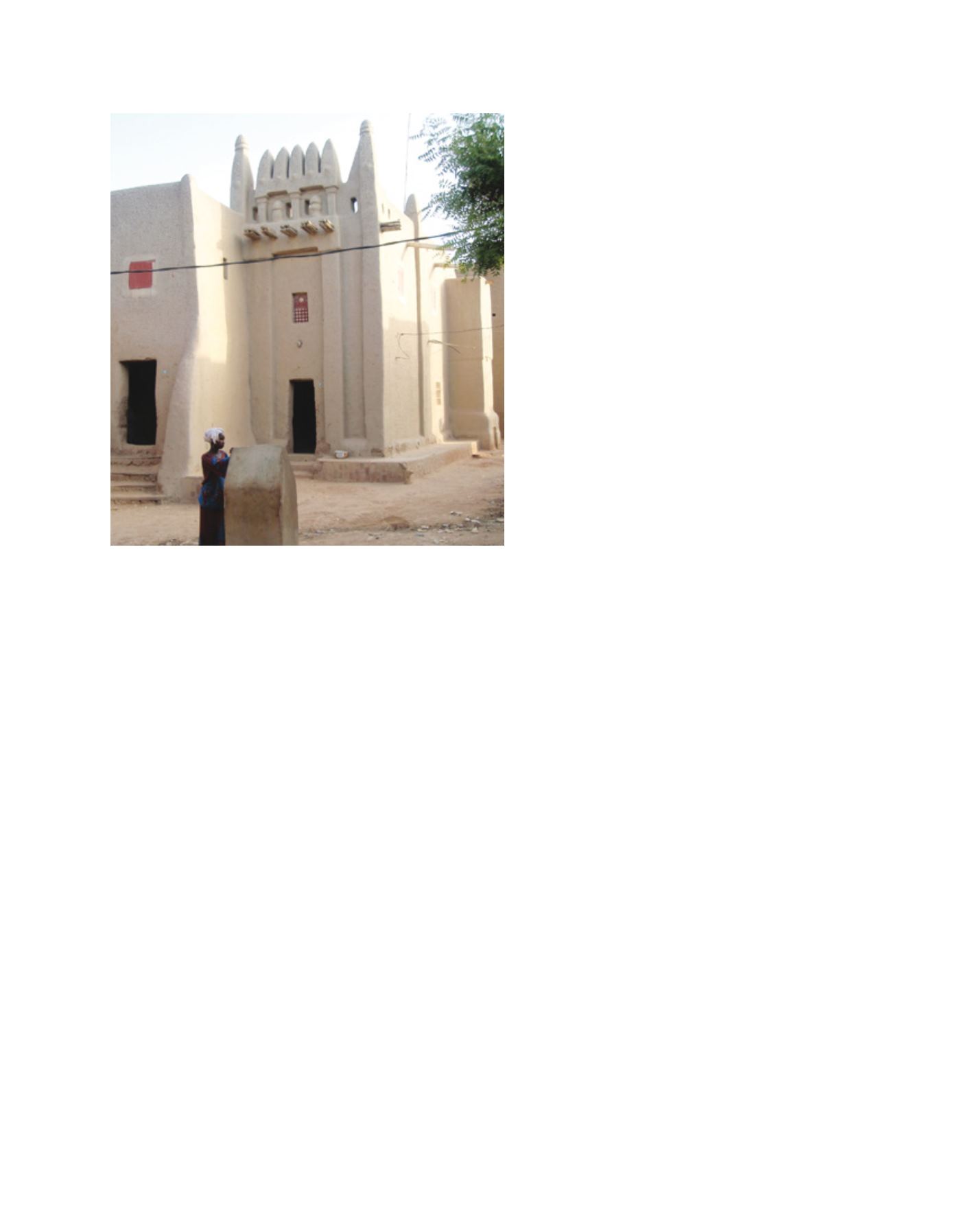

among the worst in the world. The two-storey houses of

the city of Djenné (listed as a UNESCO World Heritage

Site in 2005) are built exclusively of mud bricks

5

and

their stylish Sudanese architecture includes dry toilets

in cabins on roof terraces, usually on the second floors.

The excreta are stored in pipes built along a parapet

wall, covered with the same mixture of laterite mud and

organic material which is oil-soaked to increase tensile

strength and render the roofs impermeable. This is the

same material used to coat the walls of the houses.

In this semi-arid area, with low annual precipita-

tion and dry seasons lasting for 8-11 months a year,

temperatures can reach more than 40° C and are rarely

below 32° C. About every 20 years, the dry toilet wall is

opened and its contents collected and used as compost

in the fields. In the same way that solar radiation is used

for disinfecting water, and recommended by the World

Health Organization as a viable method for household

water treatment and safe storage, this traditional sanita-

tion technology uses cumulative solar energy that can

raise the temperature far above 50° C inside the storing

pipe, thus destroying the cell structures of bacteria. By

not ejecting excreta in the streets, the system limits

faecal contamination in the city.

A scientific study of the technology, involving the

local masson masters and aimed at scientifically updating

this traditional sanitation system, would have avoided

various inappropriate sanitation measures that have been

used – the open channels for the disposal of wastewater

and rainwater, and the easily breakable modern pipes

and collector lids designed by ‘North’s experts’ alone.

Deeper channels are traps into which infants, ageing

people and cattle fall, and some drown. All have been the

direct cause of numerous avoidable pathogens in the city,

namely in ascending order (according to the local health

centre): malaria, diarrhoea, leptospirosis (rats feeding

in the accumulation of waste) and cholera, which peak

when the channels overflow during the rainy season –

not to mention the harmattan winds that carry germs

that spread eye infections, colds and meningitis, and a

scarcity of labour that is badly needed to meet the local

community’s basic needs.

Let us hope that Mali will soon regain its traditional

peace and that the installation of new water and sani-

tation systems as planned by the Aga Khan Trust for

Culture will restore Djenné’s cultural splendour. Better

late than never.

Djenné’s stylish Sudanese architecture includes dry toilets in cabins on the roof

terraces of houses

Image: C. Brelet