[

] 252

Better late than never

Dr Claudine Brelet, HDR

T

he

Oxford English Dictionary

defines the word ‘coopera-

tion’ as “working or acting together to the same end” for

a common purpose or benefit. Unfortunately, this process

does not always take into account all the cultures involved

or what it means for them, whatever virtuous intentions are

proclaimed. Who can say that most international cooperation

projects to ensure sustainability and poverty eradication respect

local cultural practices and values?

In the water sector, the approach is still too often based only on

hydrological and climatological data, on modelling and engineer-

ing, all relying on the application of scientific and mathematical

principles to practical ends such as the design, manufacture and

operation of efficient and economical structures, machines,

processes and systems. Economy, too, is not sufficient to under-

stand cultural practices linked to water. However

brilliantly designed international cooperation water

projects are, too many have eventually failed to meet

the tangible and intangible needs of local communities

on a long-term basis because they did not integrate

cultural practices linked to water.

Integration means the participation and involve-

ment of all individuals, especially the poor, from the

beginning of a project’s planning process to its manage-

ment, monitoring and maintenance. Achieving true

integration entails valuing the experiences, knowledge

and narratives of women and men who live with and

because of water. Integration also means transparency:

access to clear information is necessary to ensure that

local communities can understand the changes they

may have to face in their traditional lifestyles. It can

also ensure that one interested party will not disadvan-

tage others. It is easy to publish figures and numbers,

but these fail to ensure that a project is successfully

integrated because they do not take into account living

human reality, especially its intangible dimensions. A

common challenge for experts is to translate scientific

terms and concepts in a way that is understandable to

civil society, especially when communities have a life-

style that relies on beliefs that largely differ from those

of modern science.

The modern scientific paradigm does not take into

account the way populations view themselves, their

own paradigm or ‘cosmovision’ that gives a meaning

to their place in the universe and in nature – in

short, their culture. Too often, international experts

forget that the term ‘culture’ does not mean the liter-

ary and artistic achievements of ‘cultured’ elites only.

Culture involves the social, spiritual and technologi-

cal dimensions of human life, learned patterns of

behaviour, thought, normative values, knowledge

– namely a way of life – which for generations have

been shared by the members of a society to meet

its basic tangible and intangible needs. The World

Conference on Cultural Policies

1

adopted the cele-

brated anthropological definition of culture that links

it so irrevocably to development. According to this

definition, culture is “the whole complex of distinc-

tive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional

features that characterize a society or social group.

It includes not only arts and letters, but also modes

of life, the fundamental rights of the human being,

value systems, traditions and beliefs.”

W

ater

C

ooperation

, S

ustainability

and

P

overty

E

radication

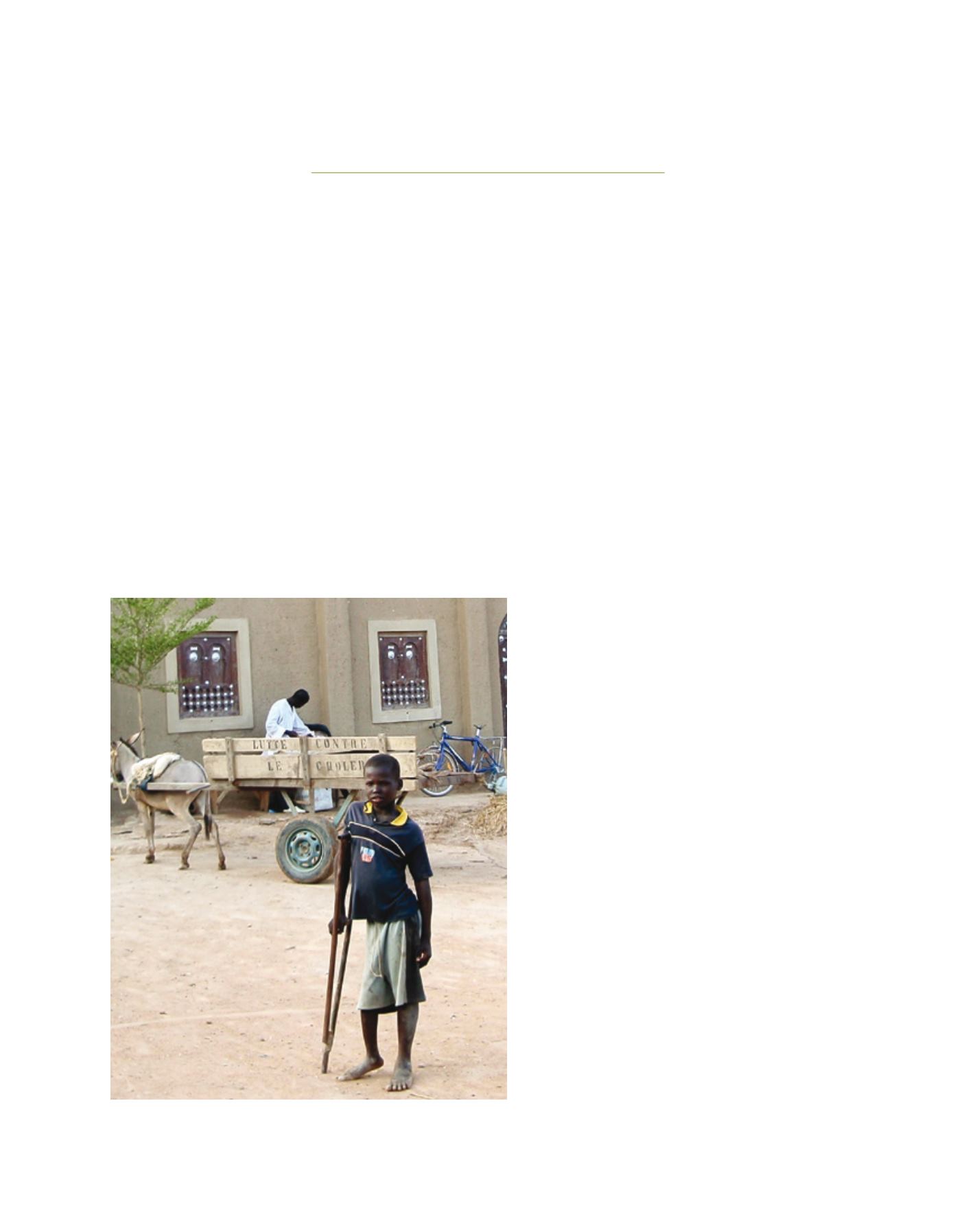

Polyomyelitis and cholera are among the pathogens caused by inappropriate

sanitation measures

Image: C. Brelet