[

] 250

W

ater

C

ooperation

, S

ustainability

and

P

overty

E

radication

the sustainable development objectives of different stakeholders,

to identify the ecological, economic and social factors that affect,

or may affect, a given site, tools to resolve conflicts, and to obtain

resources to find sustainable solutions.

Where wetlands and their water catchment basins are shared between

different countries, or different administrative areas, cooperation for

the long-term use of their resources at a transboundary level, taking

the needs of the entire ecosystem and water catchment into account,

is an urgent need. And such cooperation is a process that develops,

often passing different steps that may individually take much time to

be achieved, in order to move on to the next level of integration and

coordinated action. Local non-governmental stakeholder organizations

are often among the first ones to understand the need for common

approaches and coordinated action, and to make the first moves.

Ideally they will do so with the support of local authorities, enabling

the creation of the first formal contacts across artificial borders. This

should lead to regular consultations, agreements on cooperation, and

joint activities. The next steps of integration proposed in the Ramsar

guidance are joint planning exercises and the elaboration of common

management plans and interventions. Eventually, shared sites and

catchment basins would be administered jointly by the respective

institutions in charge in each country concerned.

Real life experience shows the most challenging initial factors to

be the need to create trust, mutual trust among the neighbours and

the different administrations concerned. Confidence and trust among

the partners, the vision and belief that together, they can identify

shared and common vital interests, and at the same time acknowl-

edging that there can easily be potentially harmful side effects and

consequences, created through activities that support

only unilateral interests. As well as political vision and

will, transboundary cooperation needs dedicated staff,

sufficient time and patience. One of the primary needs

is to find a common language. Speaking literally about

the same idiom, but also in terms of expressions that

need to be understood in the same sense by stakehold-

ers and geographical neighbours who have possibly

very differing backgrounds and individual histories.

Information and data, as well as their analyses, need to

be shared in a transparent way. This is likely to trigger

and to be followed by common monitoring and research

programmes. Hopefully, these are benefiting from a

pragmatic exchange of equipment and services. Such

exchange can lead to the joint development of rules

and responsibilities, including joint management plans.

Undertaking joint training, regular exchange of staff and

disseminating concrete experiences rapidly increases

the know-how and intervention capacities, notably at

transboundary level. In this way, mutual benefits can be

achieved and be recognized more widely. The dissemi-

nation of best case and other success stories benefits the

raising of awareness and implementation capacities.

On the European continent – where many, often

smaller, countries meet in a restricted continental space

– national borders are abundant. This can result in the

splitting of functional water catchment basins and indi-

vidual wetland sites into two artificial entities, which

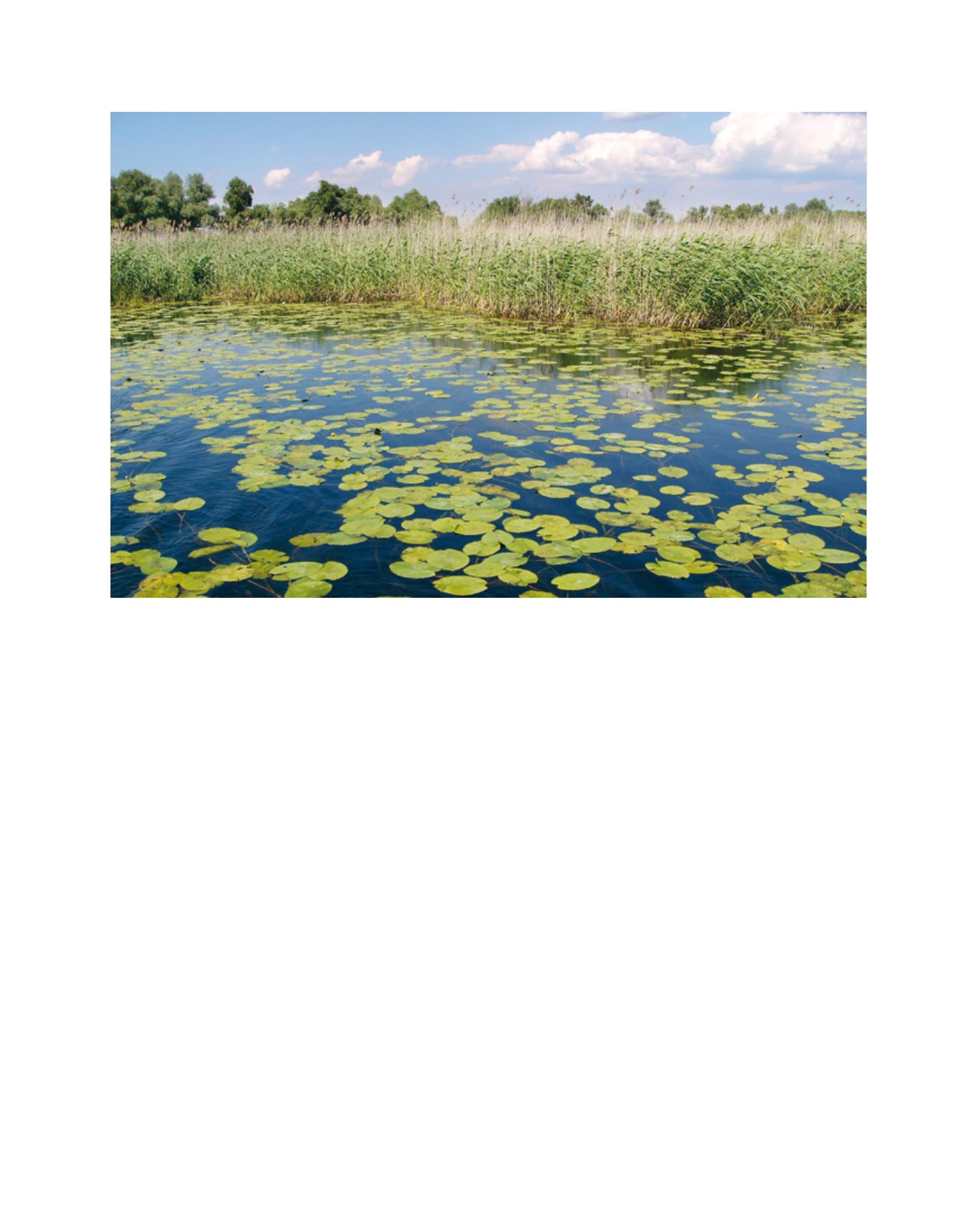

A view of the Romanian section of the Danube Delta, part of a potential Transboundary Ramsar Site shared between Moldova, Romania and Ukraine

Image: T.Salathé/Ramsar