[

] 258

E

conomic

D

evelopment

and

W

ater

the plan and members of LNRA, on the grounds that they did not repre-

sent the interests of all stakeholders, and it was stalled just as it became

apparent that the lake was continuing to deteriorate. Evidence of its

ecosystem disruption by exotic species and loss of papyrus was already

clear, but now its eutrophication – enrichment – by the combined

impacts of soil erosion from catchment smallholder cultivations, nutri-

ent run-off from lakeside farms, and the impact of thousands of people

living without sanitation within a mile of the lake’s edge, was made

obvious by cyclical blooms of noxious blue-green algae.

Strengthening water cooperation

The first organization to take a positive initiative towards sustain-

able management of the lake in the new century – reviving water

cooperation – was the Lake Naivasha Growers Group (LNGG),

consisting of the major horticultural companies, some of whom

were also members of LNRA. LNGG commissioned consultants to

conduct an accurate water balance, which could form the basis of

a sustainable abstraction policy. By this time it was known that the

2002 Water Act would soon become law, so the policy could be

developed under this and not the stalled Management Plan.

The Water Act, implemented in 2005, was the country’s first

legislation to enable community participation since independ-

ence in 1963. It established a new authority, WRMA, with seven

basins within Kenya. WRMA was charged with establishing Water

Resource User Associations (WRUAs), to comprise all ‘legitimate

stakeholders’ for subcatchments within these basins. The catchment

of Lake Naivasha is within the Rift Valley basin with 12 WRUAs, the

most advanced of which is the Lake Naivasha WRUA (LaNaWRUA),

due to the history of moves to achieve sustainable use of the lake.

LaNaWRUA was registered as a society in June 2007 and elected its

first officials in October; in 2008 it signed a memorandum of under-

standing with WRMA to promote sustainable water management

in the catchment; in April 2009 it submitted a Water Allocation

Plan and Sub-Catchment Management Plan (SCMP) based on the

commissioned hydrological study.

WRUAs are open to membership of any water user who

has or should have a permit for extraction. LaNaWRUA

has six categories of water users – individuals, water

service providers, tourist operators, irrigators (divided

into groundwater and surface water), commercial users

(such as fish farming, power generation), and pastoralists.

The executive committee consists of two representa-

tives from each category, elected by category members.

LaNaWRUA has non-user members, called Observer

Members, without voting rights. LaNaWRUA recognizes

a wide range of stakeholders and seeks to enrol them in

local environmental management. It recently prepared an

SCMP which lists 42 stakeholders represented by other

WRUAs. These were slower to become constituted than

LaNaWRUA, but by 2010 all were in operation, being

guided under an ‘umbrella’ of all WRUAs, by Naivasha.

Over the same period, LNGG began to develop a

Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) project. This was

originally conceived as a means of restoring the papyrus

that had been destroyed around the lake, so that the

growers would have a clear link between their payments

and the ecosystem service they were restoring. It was

later developed into payments for upper catchment

small farmers at the foot of the Aberdare mountains,

who were thus encouraged to grow trees and terrace

their land to arrest erosion. The scheme has proved

successful with the farmers, who have developed alter-

native livelihood streams as well as holding back their

soils, but it has not been possible to measure any subse-

quent improvements in the river or lake waters.

Water cooperation blossoms

During these developments, Kenya experienced a

prolonged drought. Between mid-2007 and the end of

2009 the water levels of Lake Naivasha dropped almost

3 metres, to a level that had not been experienced since

1946. This aroused international concern from the

media, irrigators, the customers of the cut flower produc-

ers and their governments. The WRUAs were too young

and inexperienced to respond with the required rapid-

ity, but three series of events were unfolding that helped

them to manage the crisis and come out stronger.

Firstly, organizations alarmed by news coverage such

as European governments and international non-govern-

mental organizations like the World Wide Fund for

Nature (WWF), were encouraged to contribute to indi-

vidual aspects of the solution. WWF and LNGG funded

LaNaWRUA to complete the first ever basin-wide survey

of water abstractors, which found that almost 97 per cent

were either unlicensed or their licences had expired. All

the WRUAs, as agents for WRMA, began registering

abstractors and collecting their licence fees. LaNaWRUA

organized and agreed with abstractors, through the other

WRUAs, a ‘traffic lights’ system of lake water use: at the

red level all abstraction ceased; at amber, abstraction was

reduced; and at green, abstractions could continue to the

level that the licence allowed.

Secondly, in early 2010 Kenyan Prime Minister Raila

Odinga talked with HRH the Prince of Wales at an inter-

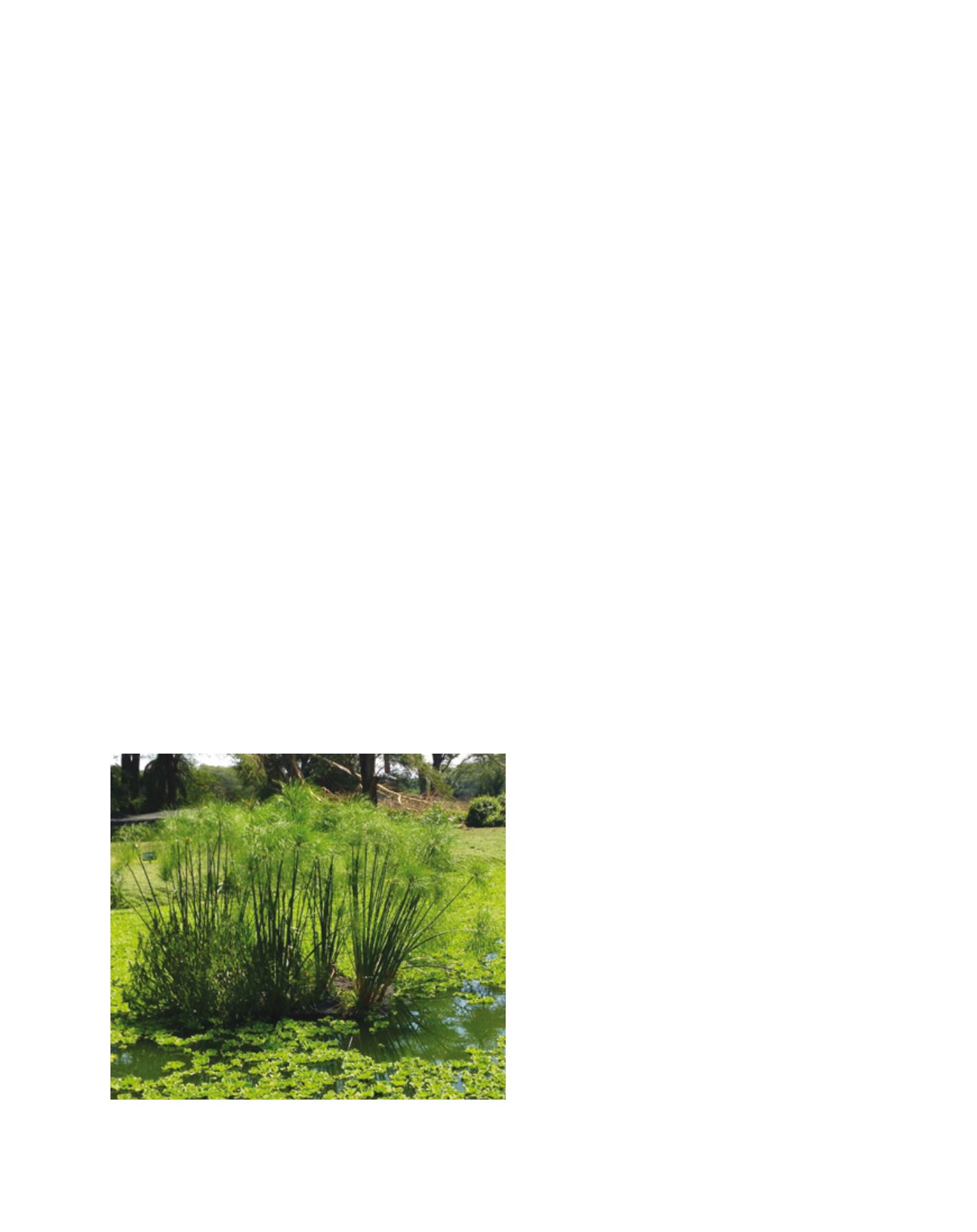

A floating island planted with papyrus at the wastewater lagoon of one of

Finlays’ flower farms

Image: David M. Harper