[

] 77

The Murray–Darling Basin Plan: cooperation

in transboundary water management

Kerryn Molloy, Senior Science Writer, Murray–Darling Basin Authority

L

ate last year, Australia brought into law its first whole-of-

basin plan (the Basin Plan, 2012) for our most important

water resource: the Murray–Darling Basin. This plan

sets limits on the quantities of water extraction for human

(consumptive) use.

Reaching this agreed limit for sustainable use of the basin’s water

resource is a world first for transboundary water management. The

basin extends across borders and has important social and cultural

values in addition to its national economic importance. Achieving wide-

scale reform depended on agreed goals, overall stakeholder acceptance

and extensive cooperation between all levels of government.

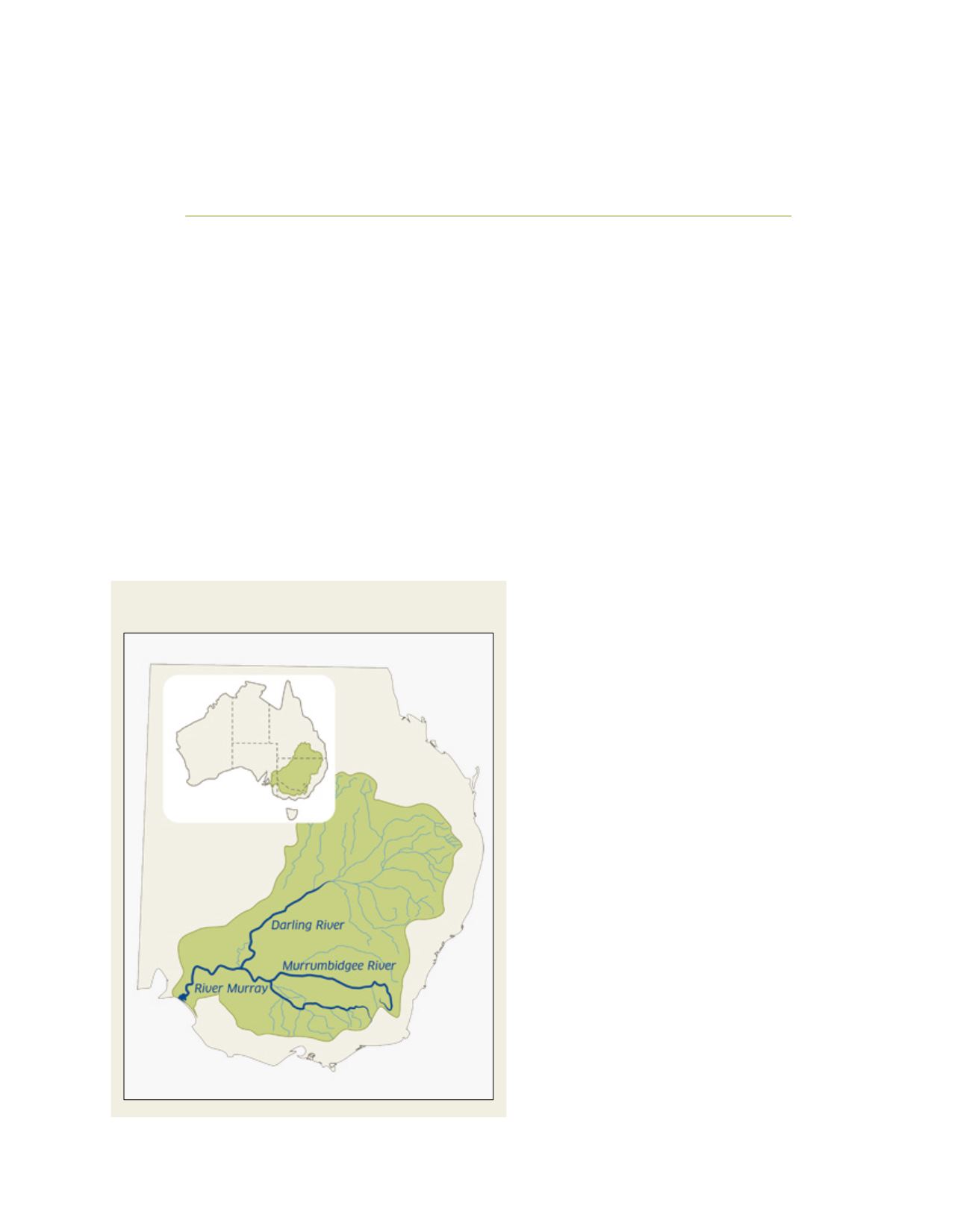

About the Murray–Darling Basin

Spanning parts of four states and all of the Australian

Capital Territory, the basin contains Australia’s largest

river system, comprising the Murray and Darling rivers

and their tributaries. Ranked fifteenth in the world in

terms of length (3,780 km) and twentieth for area, the

basin extends across 14 per cent of Australia’s land mass

(approximately equal to the area of France and Spain

combined). However, in the driest inhabited continent

on Earth and with very low topography, these long, slow-

flowing rivers have high evaporation rates (around 94

per cent of rainfall). The Murray–Darling system there-

fore carries one of the world’s smallest volumes of water

for its size. It is home to 2 million people (including 42

Aboriginal nations) and directly supports another million.

The basin’s approximately 60,000 agricultural busi-

nesses produce around 40 per cent of Australia’s food

and fibre (estimated to be worth $A13 billion annu-

ally). Around a third of this is irrigation-assisted; and

irrigation is the largest consumer of water in the basin.

Important for tourism and recreation, about 30 per

cent of the basin’s land cover is native forest; and it

contains about 60,000 km

2

of floodplain and 30,000

wetlands. Many of these are of national importance,

and 16 are listed under the Ramsar Convention on

Wetlands of International Importance. There are at least

95 threatened species dependent on basin ecosystems.

Water resource development and management

Since the mid 1800s, water resource development has

grown from initial pumping stations along the River

Murray to support settlers and livestock, to the present

where we have more than 3,000 water regulation struc-

tures. The combined capacity of the major storages is about

34,500 Gigalitres (GL). As a long-term average, 42 per cent

of the total surface water run-off to the Murray–Darling

Basin is diverted for consumption. In the connected river

systems, water is traded across and between catchments.

In Australia’s climate, supporting the economic

base without overly compromising water-depend-

ant ecosystems is challenging. The Murray–Darling

Basin receives little direct rainfall and suffers peri-

odic drought - and droughts can last a decade. In

the southern system, most rain falls across the upper

reaches of the rivers in New South Wales and Victoria,

and extraction by these states (particularly during

T

ransboundary

W

ater

M

anagement

Map of the Murray–Darling Basin, showing context

within state boundaries

Source: MDBA