[

] 78

T

ransboundary

W

ater

M

anagement

lower reaches of the system, many wetlands experi-

ence ‘man-made droughts’ in over 60 per cent of years

(compared to 5 per cent natural droughts pre-develop-

ment). Consequently, there is a reduced area of healthy

wetland, frequent algal blooms and (without flow trig-

gers for spawning) declining native fish numbers. The

removal of tree cover combined with irrigation led to

rising water tables, mobilizing yet more salt.

First steps towards wider cooperation

Developing environmental consciousness has been

spurred by periodic droughts. For example, in the 1980s

one such severe drought over the eastern half of the

continent (initiating dust storms, water restrictions and

horrific fires) resulted in economic loss of around $A3

billion. Accompanied by mounting evidence of decline,

this episode instigated many inquiries, reports and calls for

action. Essentially, a shared understanding developed that

consumption levels were more than the river system could

stand year-by-year; and there was a sufficiently compelling

case for wider cooperation for the greater good.

As a more holistic view developed of the intercon-

nectedness of all the water resources and the people

dependent upon them, the signatories to the then

Murray–Darling Basin Agreement began working

towards more effective, coordinated and equitable plan-

drought) can result in limited flow to the floodplains of the lower

reaches and out of the Murray mouth in South Australia.

Sufficient flow is vital as, in an average year, 2 million tonnes of

salt leaches out of old soils and rocks and flows down the Murray–

Darling. Without flushing flows salinity levels quickly build up,

causing ecosystem damage, threatening agricultural production and

reducing drinking water quality. Since the European development of

the basin, flow has reduced by 75 per cent on average. The Murray

mouth silts up and, during drought, remains open only by constant

dredging of a narrow channel.

In Australia’s federal system (whereby independent colonies

became states, which then joined to become the Commonwealth

in 1901), water management has until very recently remained a

power of the individual state/territory governments. While these

governments have cooperated to jointly manage the basin’s water

resource (through two key agreements: the River Murray Waters

Agreement of 1914 and the Murray–Darling Basin Agreement of

1987 and 1992), the primary focus has been on the fair distribu-

tion of water for consumption. States and the Commonwealth also

worked together to construct dams, locks and weirs to secure water

supplies, prevent undesirable flooding and improve navigability.

However, this river regulation and a quadrupling of surface

water consumption between the 1930s and 1990s unintentionally

resulted in escalating environmental problems. Water storage and

consumption has disrupted the pattern of flow and prevents most

naturally occurring small-to-medium-sized flood events. In the

Case study: environmental benefit from cooperative effort

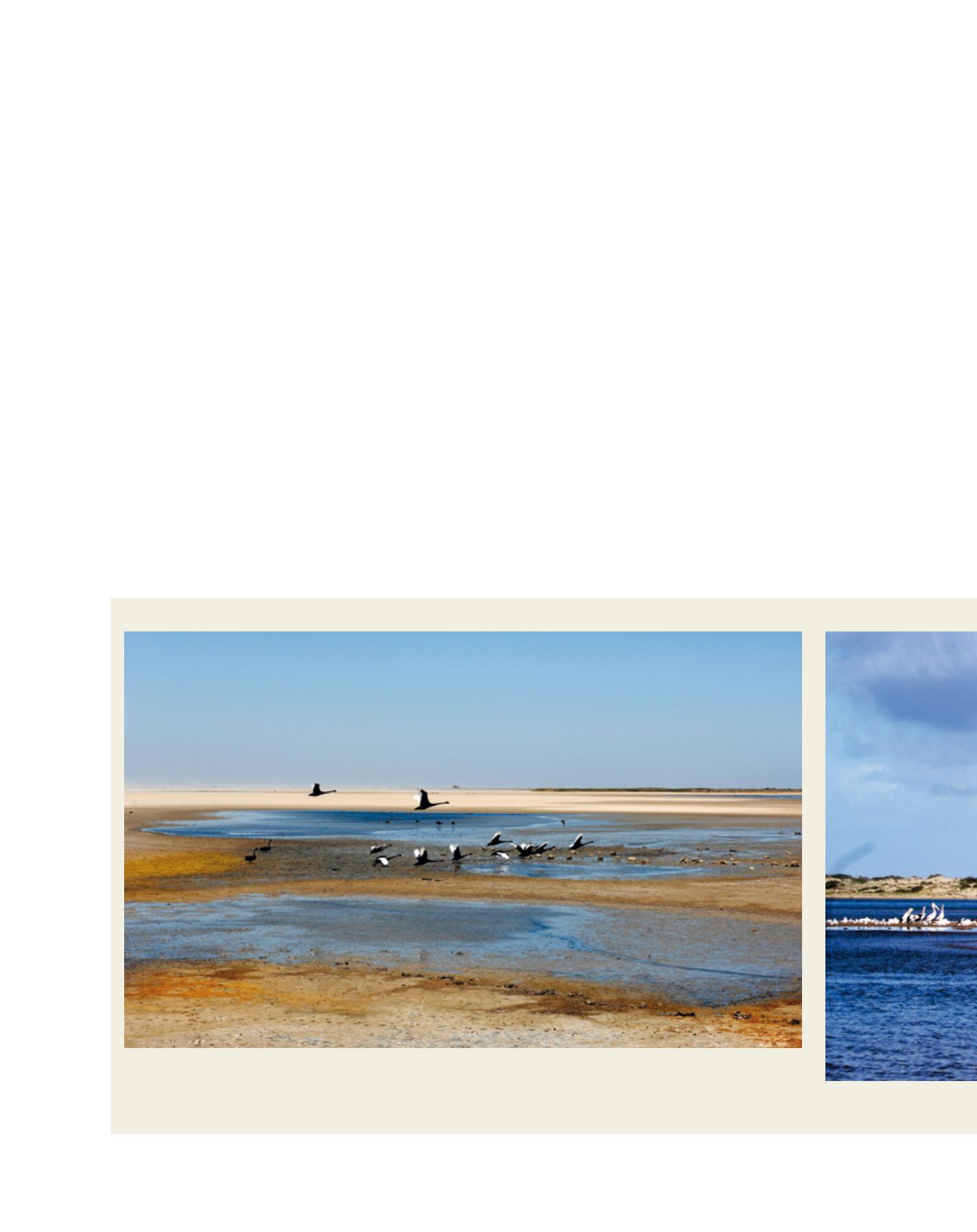

The above image shows the Coorong during the millennium drought. The bright orange patches indicate the presence of iron sulphide. If

left undisturbed and covered with water, sulphidic sediments pose little threat. However, when exposed to oxygen, such as under drought

conditions, chemical reactions may lead to the generation of sulphuric acid. When this is wet again and released back into the rivers, it

causes substantial environmental damage and serious impacts on water supplies and human health

Image: Arthur Mostead, 2008