[

] 83

T

ransboundary

W

ater

M

anagement

relatively large number of water tsars, as well as masters of moun-

tain peaks, and all their names are unknown. However, according

to some ethnological data, a considerable number of names reflect

the physical properties of water.

Notably, shaman categories and concepts formed by natives living

near the lake further intensified the parameters for perceiving the

surrounding space. The creation of myths by Siberian indigenous

peoples and their shamanistic culture as a whole prove the current

opinion of scientists on the joint process of developing the area

around Lake Baikal. When Russians came to the area, the spiritual

part of the lake’s perception did not change but was transformed to

some extent. In Siberian Russian-speaking folklore stories, legends,

and songs, Baikal, called the ‘Holy Sea’, is presented as an epic hero,

personifying the beauty and strength of Siberia.

Hence, nature plays an important role both in Mongolian and

Russian cultures and a traditional way of life is built on great respect

for the environment. Until recently, there was a taboo against living

on the shores of the Holy Sea. In the Republic of Butyatia there

are 111 water monuments, including three glaciers, 61 springs, two

rivers, 33 lakes and 12 waterfalls. A 5.7 million km

2

area of Lake

Baikal’s basin in Mongolia (18.9 per cent of the overall protected area

in the country) has ‘protected’ status. The Mongolian Government

took the responsibility of enlarging the network of protected sites on

Lake Baikal and included a few more in 2011. At present, there are

five specially protected nature sites, 10 national parks, four nature

reserves and four monuments of natural and historical

heritage along the Selenga in Mongolia.

2

In the twentieth century, the Russian and Mongolian

governments concluded a number of transboundary

agreements aimed at the preservation of natural resources

for people living around the Baikal region. In 1995,

the bilateral agreement ‘On Conservation and Use of

Tansboundary Water Resources’ was signed. Prior to this,

agreements signed in 1974 and 1988 were enforced. In

2000, an agreement between the Academy of Sciences of

Mongolia (ASM) and the Russian Academy of Sciences

(RAS) on scientific cooperation was signed. Within the

framework of the agreement, the Mongolian water ecosys-

tem study programme was adopted. In July 2001, the 4th

Meeting of the Authorized Representatives of the Russian

and Mongolian Governments in Ulan-Bator approved a

programme of joint ichthyologic research on fish reserves

in the Selenga river within Mongolia and Buryatia.

Mongolia and Russia exchange information on a

regular basis. In 2006, joint planning of water basin

management was discussed. In 2008, a broadened

list of pollutants was made, with agreement that the

dumping of pollutants should be controlled by both

parties. In 2011, a meeting was held in line with the

agreement ‘On Conservation and Use of Tansboundary

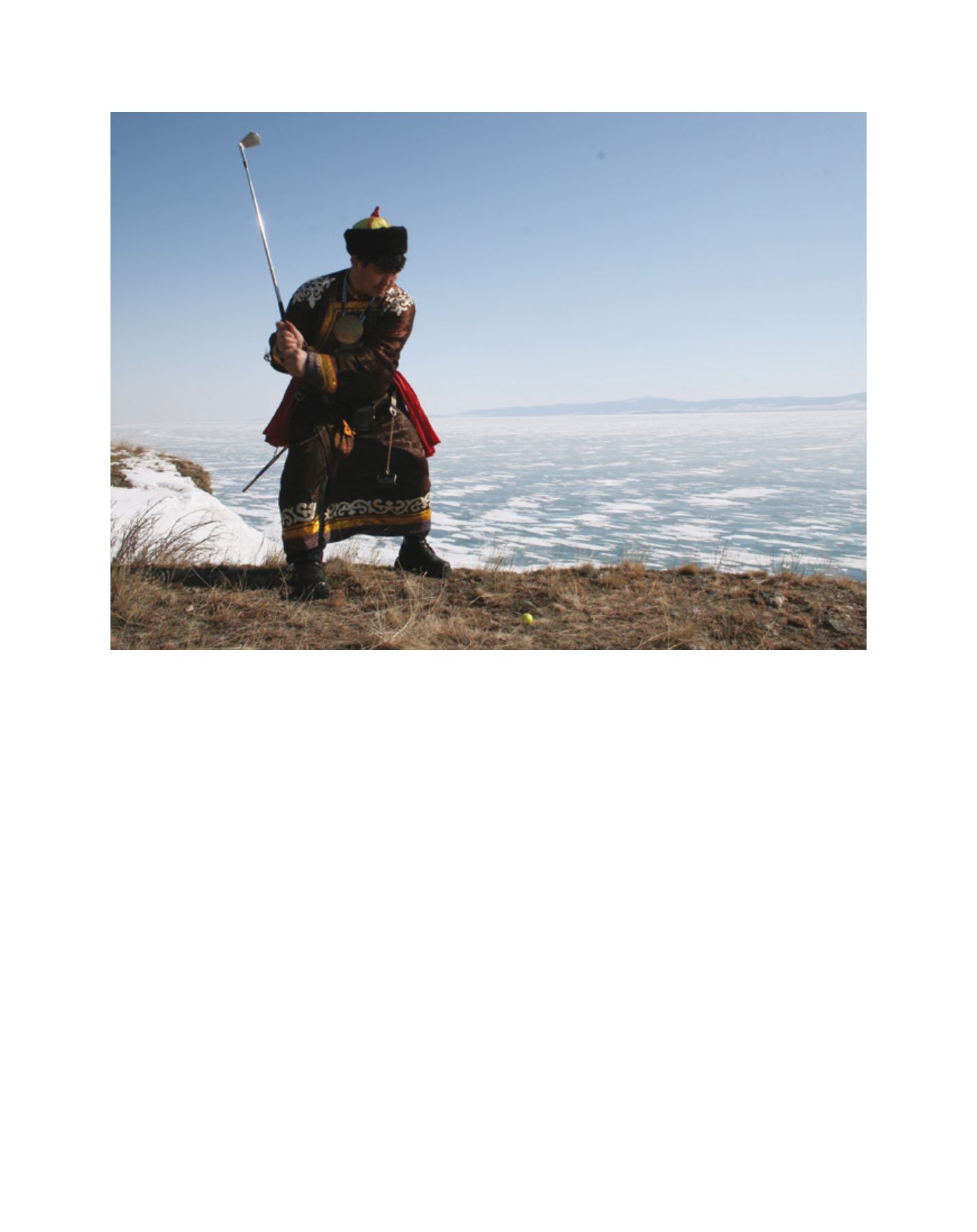

Recognizing human beings as part of the ecosystem is a key component of natural resources management

Image: Evgeni Kozyrev