[

] 82

T

ransboundary

W

ater

M

anagement

the condition of its ecosystem. Nonetheless, preserva-

tion of the lake is impossible without the joint efforts

of both Russia and Mongolia. There is a clear need for

joint support and activities aimed at the preservation

of biodiversity and the health of water and land ecosys-

tems to ensure that the systems can sustain required

functions for future generations.

Before detailing current mutual efforts to preserve

this valuable resource, it is important to clarify how

past generations of people who have lived in the Baikal

region have perceived the sanctity of the lake and

preserved the natural objects that surround it.

Ecological traditions of the Baikal region’s aboriginal

people developed over time and had their own history.

The nature of the Baikal was always acknowledged

in the Central Asian world. For example, according

to Genghis Khan’s edict, the area around Lake Baikal

was proclaimed a reserve. Any activity causing harm

to nature and the gods was outlawed. A prohibition list

was created, which was in essence an ecological code

of that time. Siberian people attributed a soul to nature.

They had practiced careful treatment of the Baikal and

its adjacent territories for centuries. Developing the

idea of man’s reliance on natural powers, indigenous

people and Russian newcomers deemed that any

disease, including any accidental and minor ailment,

was nothing but punishment from the local spirits who

protected the Baikal. People, in their turn, longed for

the Baikal’s protection, using adjacent unique natural

objects such as minerals, springs and therapeutic mud.

The indigenous populations of the Baikal region adapted

their households to the local natural conditions.

Humans developed a special attitude towards objects

of a colossal scale that engendered a terrifying supersti-

tion. Such objects were seen as sacred, and myths were

created around them. Lake Baikal is a huge water reser-

voir, surrounded by high mountain ridges on almost

all sides. Therefore, the myths created by people who

inhabited the pre-Baikal area in ancient times were

focused on the spiritualization of water and mountains;

a feature that is especially notable in Buryat myths. This

idea can be traced in a series of cosmogonic myths. In

all cases the action takes place on Lake Baikal or in its

waters. In this regard, water is seen as an original, crea-

tive element and a medium of conception and creation.

Mountains are inseparable from water in myths, and

the two are merged into a twofold invigorating source.

It was quite natural that the heroes of ancient Buryat

myths asked their ‘parents’ (the elements that created

them) for protection and salvation. They formed an

original unanimity of water and mountainous powers,

which was reflected in the process of giving names to

natural objects. With the development of shamanism,

which arose in the ancient historical epochs, human life

was related to water which, being valued as a source

of life, was saturated with greater sacral diversity.

‘Khaty’ or water spirits appeared, living near the lake

and a concept of ‘water tsars’ was formed. These had a

celestial origin and were light and virtuous. There is a

phenomena, characterizing contemporary geological activity, are

the most apparent in this area. The main threats to the Baikal and

Selenga basins are climate change, industrial development, increas-

ing pollutants, destruction of habitat, reduction of biodiversity, and

influx and adaptation of alien species.

The length of the border between the Russian Federation and

Mongolia is 3,488 km. In Mongolia, 25 rivers flow in to the Selenga

and the main part of the Selenga river basin lies on the frontier with

Russia. This part of Mongolia, called the Han-hai, is the core of the

country’s economy. It plays an important role in addressing social

development issues and has great potential for economic growth and

favourable conditions for living.

The total area of the region is 343.2 km

2

, or 20 per cent of the

overall Mongolian territory. It includes 122 districts (somons) and

eight provinces (aimaks) partially or fully. The average population

density of Mongolia is 1.8 people per square kilometre; but along the

Selenga river basin, it is 4.4 people per square kilometre. In 2011, the

overall population of the Selenga river basin was 2.1 million people,

representing 73.6 per cent of the total population of Mongolia. The

number of city residents of the region has notably increased.

Major industrial cities of the country are located on the shores

of the Selenga tributaries. The largest industries are located in

Ulaanbaatar, Erdenet and Darkhan. These include the Erdenet, Gobi

and Darkhan metallurgical companies, carpet and cashmere wool

companies, lambskin coat factories and meat processing and packing

plants. Such a concentration of people and economic resources leads

to an intensified anthropogenic impact and ecological problems.

It is clear that the Selenga river plays an important role in forming

the hydrological, hydrochemical and hydrobiological regimen of

Lake Baikal. Its delta is a natural biofilter and indicator of the lake’s

condition, and this necessitates a complex scientific assessment of

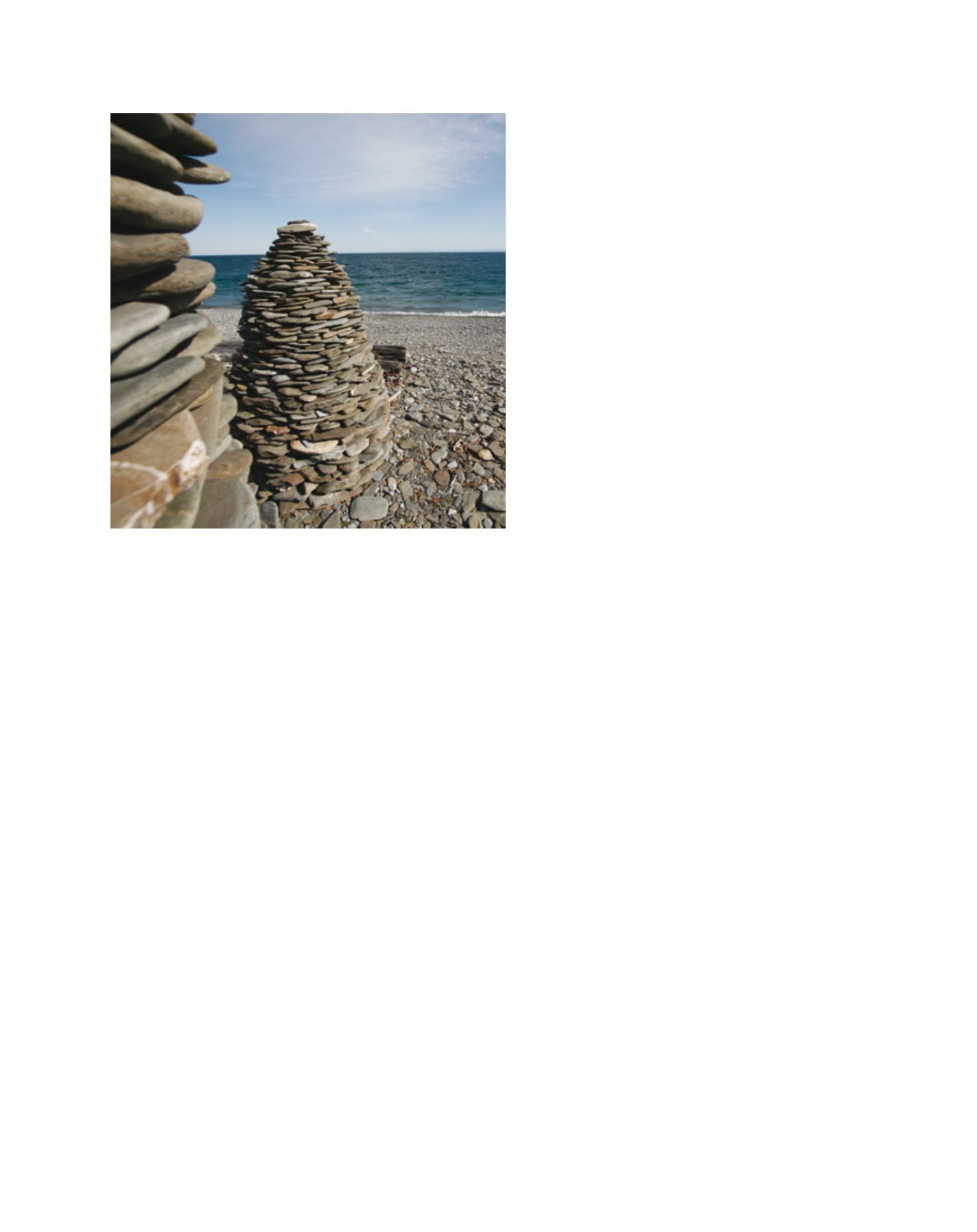

The nature of the Baikal was held sacred by local people and there are many

monuments in the region

Image: Evgeni Kozyrev