[

] 79

T

ransboundary

W

ater

M

anagement

ning. Indeed, the tagline for the new cooperative effort was: ‘Six

governments working in partnership with the community’.

Functional institutions developed to underpin this (reflecting

the aim of political, bureaucratic and community-level coopera-

tion). These were the Murray–Darling Basin Ministerial Council

(political arm); the Murray–Darling Basin Commission (bureau-

cratic arm) and a Community Advisory Committee. In practice,

while this cooperation produced many good initiatives including

a successful salinity and drainage strategy, improvements in algae

management and better water accounting, it did not prevent an

overall increase in water extraction as this was driven by national

and global market forces.

Another intense drought in 1991-95 reduced average rural

industry production by around 10 per cent, despite diversions

actually increasing by about 8 per cent to support the northern

basin’s expanding cotton industry.

With awareness that further increases could not be supported,

this crisis created an opportunity to ‘make good’ on earlier commit-

ments. This time, the Murray–Darling Basin Act 1993 gave legal

force to a new cross-jurisdictional, cooperative governance model.

The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) formed to oversee

national-level cooperation on issues of strategic importance and

cross-jurisdictional concern, including the environment. COAG

(consisting of the Prime Minister, State Premiers, Territory Chief

Ministers and the President of the Australian Local Government

Association) was underpinned by a Murray–Darling Basin Ministerial

Council (MinCo) which had the responsibility of bring-

ing the Murray–Darling Basin Act to life.

Cooperative reform to limit consumption

The partnership embodied inMinCo initiated the first thor-

ough basin-wide audit of water use, completed in 1995.

Confirming that river health issues would become critical

if diversions increased (likely under the existing allocation

system), the audit also predicted risks to long-term water

security for existing irrigators and critical human use. This

prompted MinCo, after independent review, to institute

the first ever limit (the ‘Cap’) on consumptive water extrac-

tion. This was an important initial step towards finding

a sustainable limit for extraction. However, it reflected

capping at existing consumption levels rather than any

thorough investigation. Indeed, despite Queensland

joining the Murray–Darling Basin Agreement in 1996 and

the Australian Capital Territory in 1998 (meaning that

all basin governments were signatories for the first time),

overall diversions actually continued to increase until

1999 through the legacy of over-allocated entitlements to

water and different state accounting systems.

The National Water Initiative (2004) followed: a

blueprint for reform towards addressing over-allo-

cation, enhancing security of water access rights and

removing the remaining barriers to trade.

From July 2012 to January 2013, around 1.2

billion litres of stored environmental water was

released, coordinated to maximize outcomes and

efficiency. Firstly, it improved instream health

along the Murrumbidgee, Goulburn and Murray

rivers as flows moved downstream. Through

mobilizing carbon and reducing nutrient loads

and salinity, conditions improved for native fish

and riverine vegetation. Secondly, a timed pulse

of water (December 2012) acted as a trigger

for spawning and recruitment in large-bodied

native fish. Finally, on reaching the end of the

River Murray system, flows were sufficient to

breach weirs, flush wetlands and improve the

estuary (important for migratory fish movement).

With increased food for wading birds in the

Ramsar-listed Coorong near the Murray Mouth,

aerial waterbird surveys detected an increase in

waterbird diversity and increased breeding due to

a marked increase in mudflat food sources and

habitat. The endangered southern bell frog has

also been recorded in a number of wetlands.

This complex delivery involved cross-jurisdictional

accounting and the passage of large flows

through four river systems and across borders.

Its achievement drew on many cooperative

relationships, with water contributed by the

Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder,

MDBA (through TLM), state governments and

private donations. Its delivery was made possible by

ecological and technical experts working together

with water delivery partners (such as catchment

management authorities) and river operators

responsible for controlling storage releases.

This cooperative effort produced the largest ever

targeted delivery for environmental benefit purposes.

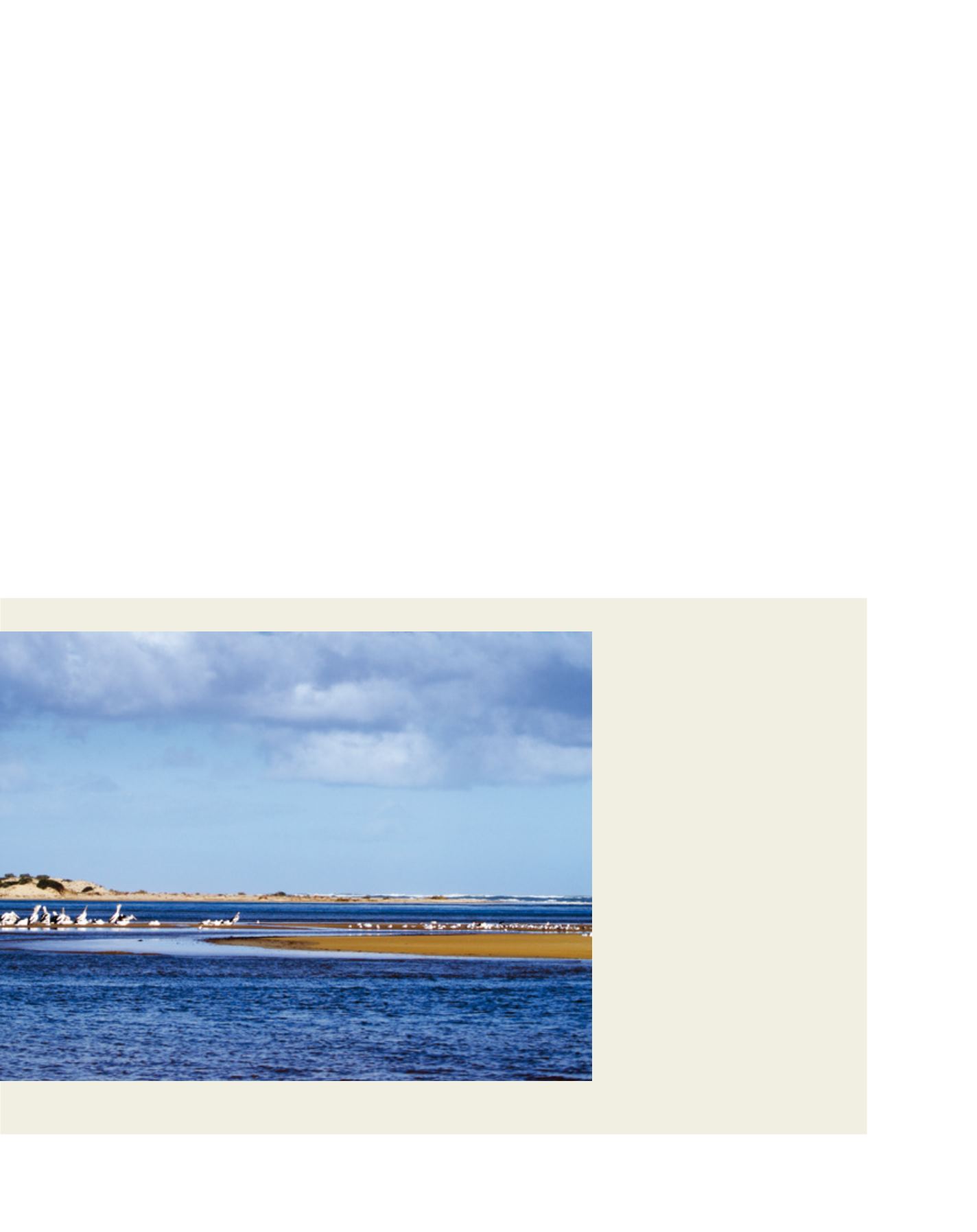

A healthier Coorong (a TLM icon site) after rainfall and environmental water releases reconnected the

Lower Lakes with the sea

Image: Denise Fowler, 2011